Havergal College THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Havergal College, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Our Kids editor speaks about Havergal College

Basics

Havergal is the largest girls’ school in Toronto, both in terms of student population and physical space. It has a well-earned reputation for doing things differently and for charting its own path, both academically and culturally. As such, it continually gains a special place in the hearts of its students, and in the heart of the city as well. It’s visible within the culture of Toronto in ways that many other private schools aspire to.

Havergal offers a liberal arts education and includes a Junior School, comprising JK through Grade 6; a Middle School, comprising Grades 7 and 8; and a Senior School, comprising Grades 9 through 12. The junior program is housed in its own building, and it and the Upper Schools sit somewhat apart from each other, linked by a walking bridge that crosses a ravine that separates them. Each has its own entrance, with the Upper School entering from Avenue Road, and the Junior School entering campus from Rosewell Avenue, a residential street which follows the property’s eastern boundary.

The façades that present to Avenue Road remain, for the most part, those of the original buildings at the location completed in 1926, and they are responsible for the image of the school that many people have. The presentation is very traditional and, if we’re being honest, can seem a bit cold or standoffish. Inside, the feel—despite the stonework and the leaded-glass windows—is friendly and collegial, as supported by relatively recent additions (the dining hall and commons in particular) where the students congregate.

Structural developments are largely sympathetic to the original building, and have also created a more porous interface between the indoor and outdoor spaces, all absolutely welcome. Glass doors open out to shared spaces within the centre of the Upper School. When we visited, there were girls beavering away on some sculpting projects in the quad. Indeed, there are lots of good introductions to the life of the school, and that kind of thing is one of them. Another is simply sitting for a time in the lobby. The security guard at the desk greets students and visitors, and he seems to not only know all the students by name, but also how they like their pizza, and where they should be in 10 minutes. We visited on the same day as one of the alumni teas—there are two of these each year—and Old Girls, all strikingly animated, made their way into the main hall. The Old Girls—and these in particular were the very oldest of the Old Girls, the tea being for those who attended in the '60s and earlier—are very present within the school consciousness, even when they’re not physically on site.

It’s charming in all kinds of surprising and unexpected ways. The staff room is one of those places that is so peaceful, so convivial, that it’s hard to leave. The school has learned a lot of lessons right, including how to build an engaged faculty that is dedicated to the long haul. Many have been here for years and years, and while some have come from careers at other independent schools, they typically leave Havergal only by retirement, and then only forcibly so. Two members of the faculty retired at the end of the last school year. When presented at morning Prayers, there was clearly a great reluctance to leave on both sides of the ledger, faculty and students. The music teacher had her students present a piece from various points in the hall, and lots of dewy eyes were a direct result. She also shared photos of her life, including her childhood, and that kind of openness—a willingness to share lives, not just classrooms—is apparently all part of the Havergal experience.

“Havergal really focuses on the girl and helps her to find what her power is.”

—Roslyn Mounsey, parent

Certainly it’s often the little things that signal the health of the school, and Havergal has them in spades, from the teas, to the art on the walls, to the bustle of the dining hall, to the girls huddled around the perpetual jigsaw puzzle outside the guidance offices. The school’s reputation is strong, though it’s only part of the story. A visit to the school—including a sit in the lobby or the dining hall—recommends Havergal in ways that the history, or the alumni, or even the reputation can’t.

There’s a lot of bustle beyond the boundaries of the property, and Avenue Road is a major artery. The size and setting of the campus create a significant buffer, and even the playing fields which abut the property boundaries feel removed from the surrounding city life. Traffic on campus, too, is minimal, and parking lots are at a remove. The spaces that the students work and live within are nicely contained, while the interface between them is free of vehicular traffic.

The sense of place while on campus is consistent and, frankly, bucolic. This is all thanks to the foresight of founding principal Ellen Mary Knox when choosing the property more than a century ago. This kind of campus, at this location, would not be possible to create today, and it is one of the great assets—along with the history, tradition, and leadership—of the school.

The school has grown over the decades of its life, and the programs have as well. The size of the school allows for a breadth of offerings that is uncommon in single-gender schools, and that is often a principal draw for the students that attend. More than anything, though, is the tradition of empowerment that has become the core of the school’s mission.

Parent Roslyn Mounsey is somewhat typical in that she first turned to Havergal because of the reputation of the academic program. “I think we were drawn to Havergal really out of a quest for an environment that would be challenging. Catharine had always excelled in school and, at that time in public school, was under challenged and not required to work to her full potential.” After three years’ experience with the school, however, it’s the culture of the school that is at top of mind. “I think she’s been stretched in a different direction … the school really takes an initiative,” says Mounsey. “Havergal really focuses on the girl and helps her to find what her power is”—and to take it forward into the world.

Key words for Havergal College: Community. Opportunity. Empowerment.

Background

Ellen Mary Knox was the founding principal of Havergal, and she led the school through the first three decades of its life. She remains the longest serving principal, and while her term was completed in 1924, the stamp of her leadership very much remains. Knox was, to put it mildly, a woman of action, as well as a first-rate character. She was born in Surrey, England, and grew up the product of a proper Victorian girl’s education. She graduated Cheltenham Ladies College—still one of the top schools in Britain for young women—and left all of that prestige and comfort to come to Canada, which was at that time a nation still being formed. She was attracted to the adventure that Canada represented, and the opportunity to make something out of nothing through the application of raw talent, determination, and elbow grease. She wanted to challenge girls to “enlist whole-heartedly in the struggle … [and] place yourselves at the strategical point where you can serve your country best.”

“The school cared about the education of women long before most women began to take themselves seriously.”

— Catherine Steele, class of '28

Time and again, she did exactly that, including very actively creating a space for women in politics and business. For Knox, struggle was the path to freedom. She wrote to her students in her guide for girls, The Girl of the New Age, “You are not going to settle down on the one legged stool of your father's money … You are not going to follow the whim of the moment … [there are] new adventures everywhere around you, the avenues of work opening out on every side, avenues which a few years ago you never believed could have been possible to you.”

One of the new adventures that Ellen Knox was thinking of was university. While female suffrage was still years away, University College and Trinity College (now both part of the University of Toronto) had begun graduating women in 1880 and 1883, respectively. A university education was a possibility for Havergal students from the school’s inception, and Knox was intent on delivering as many girls there as she possibly could. She also wanted them to be examples for other girls and women, able to succeed in ways previously not thought possible, in academics, the arts, leadership, athletics, and life.

That was the seed from which she grew Havergal. Knox arrived in Canada in 1894 with the intention of taking over Morvyn House, a school founded in 1864 and which, by all accounts, had seen better days. It’s invariably described as shabby in accounts from that time. Knox later recalled that, on seeing the school for the first time, “the one spot of cheerfulness was a loaded crabapple tree under the staircase window, making a splash of brightness in the otherwise dispirited surroundings.”

She probably loved that, seeing it as a great opportunity to build it better than it had been before. And that’s exactly what she did. She dug in and shepherded the school through a development of the Jarvis campus, near Carleton Street, to the acquisition in 1926 of the parcel of land on Avenue Road, where the school remains today. No sooner had the ink dried on the deed for the new property than she had the entire student body visit the property for a picnic on her birthday, October 4, 1923. They took the streetcar as far as it went, and from there walked along Glengrove Road.

When the girls arrived they saw some farmers’ fields and, beyond that, nothing at all. “There were trees in our ravine,” wrote Catherine Steele, “but no other trees on the property!” Friends of Knox described it as “remote and undeveloped,” which it was, but the trip there was fun all the same. “It was a beautiful autumn day, and I still have a vivid memory of Miss Knox standing on the hill where the barbeque is now,” one student recalled. Some reported that there were two signs on the dirt road, one which read “Please Do Not Sound Your Claxton Horn—It Upsets the Sheep and the Golfers” and the other “The End of the Road.” Whether or not the signs were actually there, to the girls that’s what it felt like: the end of a long dirt road. They all thought Knox was nuts. But even so, they followed her, clearly inspired by her spirit and enthusiasm. And although it was a more rural setting “up north” and “in the country”—that’s how Knox described it at the time—the city quickly caught up to it.

“This is a school that embraces and celebrates all the events and the characters that have contributed to the culture of the school, and that really sees its history as a living, breathing asset.”

Tradition

“This is a place that loves its traditions,” says The Reverend Canon Susan Bell, a recent chaplain at the school. “The joke around here is that if you do something two years in a row, it’s a tradition.” Nevertheless, Bell feels that the sense of tradition gives a rootedness and a fidelity to place, the awareness of being part of something greater. “It also creates culture and maintains culture. I know that leadership is quite often equated with change, but there is a kind of discernment that needs to happen in the midst of leadership. You need to understand when not to change as well. And some of these things are fixtures that define who we are.”

The core traditions are apparent in the events that mark the school calendar—the holiday Carol Service, Founders' Day, and the House Shout held each spring—as well as in the day-to-day. Students meet for Prayers three times a week, though the experience is more akin to a school-wide assembly. “At Prayers you could sit there and say ‘this is a tradition and we have to do this,’” says student Anne Broughton. “But we really don’t. Over the years I’ve seen that everybody has that one Prayers [service] that changes your life. The one speaker that you’ll always remember.” For her, that was a student who spoke about her experience of mental illness. “I’d never heard anyone say anything like that, ever. She was onstage, she was telling her friends for the first time. It was very powerful.”

“I think it’s what makes the community strong,” says Katie Salem, a parent of the school. “It’s the daily meeting as a community, a bigger community other than the immediate community in the classroom.”

Those perspectives are clearly widely shared. “What I love most about this school,” writes Kate White, interim head of the Junior School, “is the careful blend of long-standing traditions and innovative approaches to education. There is a real sense of confidence that comes from being an educational institution for 120 years. Our strong history gives us a solid foundation to ask why we are doing things and how our values are connected to everything we do.” That can perhaps risk reading like marketing hype, though it’s very true, and demonstrated in all kinds of ways.

This is a school that embraces and celebrates all the events and the characters that have contributed to the culture of the school, and that really sees its history as a living, breathing asset. It also curates it, and has a full-time archivist in order to do so. The benefit for the students, today, is a very real, and regularly asserted, sense of participation within something greater, something valued across a very long temporal arc.

Student population

“We are a high-achieving school,” says Maggie Houston-White, executive director of enrolment. “One of my favourite things about the school is that there are so many different kids here. Different talents, different personalities.” She notes that, when assessing candidates, she’s looking for “girls who are going to, in their own ways, be eager to find out what their talents and passions are, and to really go for that, knowing that they’ll be nurtured by us along the way.”

Again, the school is large, with a total enrollment of 920 girls, though with the division between the upper and lower schools the feel is more intimate than the numbers might suggest to some. Impressively, 99% of the students return each year, ultimately graduating from the school. “It’s important that girls feel it remains the right school for them,” says Houston-White, and statistics show that a vast majority of them do.

There is a boarding program, though most of the students are day students, something which underscores the feel of the school. Annually there are about 55 boarding students; they predominantly arrive from locations in Canada, and the school is very deliberate in maintaining as much diversity within the boarding community as possible. ESL is not offered, something that perhaps limits things somewhat. “They are a small community, so they are very close,” says Houston-White of the boarding students. “They have all of the benefits of being in the city of Toronto, and being in a school that recognizes how much you can take advantage of here.” Certainly, the feel is Toronto-centric in all the best ways—there is a sense of proximity to a vast range of resources, both within the school and in the city beyond. To be sure, those resources are considerable, and the school rightly makes the most of them.

Meeting the girls, they are invariably friendly, unaffected, and full of fun. There may be snooty girls somewhere, but we didn’t find any here. “I don’t think there is one ideal student,” says Anne Broughton, a Grade 11 student. “I think I kind of fit the trope: Someone who is involved, who enjoys academics, is excited by doing new things rather than sticking to what they’re used to.”

When girls arrive, they often have been exceptionally successful in their previous schools, if not a little bit bored. At Havergal they enter a community of true peers. Zoe Mohan arrived in Grade 7. “When we were meeting all the girls for the first time,” she recalls, “that week really made an impact on me. I saw that these are my people. They’re all enthusiastic. Everyone wants to take initiative, and be really involved in what they do. I feel that none of us is afraid to step out of our comfort zones … and I thought, ‘This is my home. This is where I was meant to be.’”

There is a palpable sense of belonging that is shared among the day and boarding students, one that is based in the kinds of interactions that the school allows, and the interests and perspectives that the students share. “I feel like everyone is part of it together,” says Grade 9 student Emma McCurdy-Franks. “I’ve bonded so well with all the girls in my grade, and even other grades. We are kind of all going through it together.”

“It’s very Harry Potter,” says vice principal Michael Simmonds, chuckling. “But, you know, I’m serious. Harry Potter lived in a closet, hid his special powers, knew he was different, and had to go to Hogwarts to be empowered. There’s a lot to be said for bringing a group of like people together, because what you see in the community are examples of success in every field. … It’s a culture of empowerment.”

“I was in my first play ever in my life at Havergal College.”

—Margot Kidder, actress, class of ’66

Also like Hogwarts, houses provide a foundation for much of the social life of the school. They were introduced in 1928, and there were three that year: Ridley, Knox, and Wood. As the school grew, houses were added, and there are 10 today, all named after women who have played prominent roles in Havergal’s development. Houses compete throughout the year, with girls earning points through community involvement, athletics, co-curricular activities, as well as participation in school events. More importantly, if less obvious, the houses grant girls a sense of belonging—their own village, in a sense—and mentorship within the wider community of the school. “In the house system she has girls in Grade 12 that she looks up to and aspires to be like,” says Katie Salem of her daughter Nadia.

Social currency is gained through academics—that’s typical of any independent school with a similar focus—and there is a bit of competitiveness that sneaks in. That said, that’s not the only means for students to distinguish themselves; they typically come to the forefront in a variety of different areas, not limited only to their academic successes.

Alexandra Rozenberg is a “survivor,” that being the term used in the school for students who attend from kindergarten or Grade 1 through to graduation. “I love everything about Havergal. There’s just a lot of opportunities.” The best advertisement for the school is less found in what the students say than in how they say it, and Rozenberg is a study in that: self-assured, well spoken, with a bit of spark. “There are always people to support you,” she says of the cross-curricular projects, including one she did in Grade 6 about water consumption, “and that you have to go in with concrete ways, developing a plan of action. They’re not just going to give you something. You have to work for it.”

“There is nothing up hill or down dale so delightful as being wanted. You knew that the first day you found yourself on the First Basket Ball Team, the day you found yourself leading in your form.”

—Ellen Mary Knox, founding principal

The Junior School

“We live in an inquiry-based world, where curiosity reigns,” says Leslie Anne Dexter, past head of the Junior School, a role she has occupied since 2011. The junior program has been designed to support that understanding, blending inquiry and direct instruction to get the right balance so that all children learn, and with their own interests and curiosities at the fore.“It’s a completely different lens than it is in Middle School or Senior School.”

Dexter knows all the students by name and then some (“I know when their teeth fall out”) and makes a point of being present to them daily, just as she is to the parents we spoke with. She has lunch with the students at least twice a week, and is often seen in the mornings at drop off.

The learning environment is centered on the learning hub, the library, and the feel is very open. Glass walls provide students with a view into the various classrooms and the learning hub, and spaces are largely lit by natural light, with views to the world outside. Until fairly recently, the brook was covered over. “We daylighted the brook,” says Dexter. “We thought, ‘We need it to be open,' so we landscaped it” to make it apparent, both as a division between the areas of the campus, but also to provide a closer interaction with the nature that it supports. “The outdoors comes in, and the indoors goes out”—which, of course, sounds strange given that the school is well within the Toronto urban sprawl. Yet it’s true; the experience of nature, and its presence in a broad range of curricular and extracurricular programs, is remarkable.

“We live in an inquiry-based world, where curiosity reigns.”

—Leslie Anne Dexter, past head of the Junior School

The Junior School is removed from the Upper School, separated by the brook and the attendant green space that defines the property and, by extension, the two aspects of the school. The Junior School includes kindergarten through Grade 6, and for the most part it has a life of its own, including its own governance, faculty, and resources. The challenge for Havergal, if there is one, is to ensure that the junior program isn’t seen as ancillary to the Upper School, nor as entirely distinct. Balance is maintained in part through shared experiences, and all students take part in the events that mark the school calendar, such as House Shout each spring. Likewise, there are opportunities for mentorship to develop between the junior and senior students.

The Junior School has its own entrance and approach from the street. Its daily routines are corollary yet distinct, as are the academic and extracurricular programs. For a time, the Junior School was coed, though that remains as a moment in the school’s history. Today, appropriately, all offerings are single gender, focused firmly on educating and empowering girls into a sense of themselves and their talents.

Teachers are keen to join the school, and job postings invariably gain an impressive and immediate response. As a result, Dexter is able to hire from a rich pool of expertise. In keeping with the tradition of doing things differently, the organization of the Junior School—as with the Upper School—is unique to Havergal. It includes a head and an assistant head as well as coordinators in literacy, STEM, and math. “Those coordinators are there to make sure that teaching and learning is exactly the way we want it according to our strategic initiatives, and to move teaching and learning forward.”

Dexter is one of those people that clearly doesn’t do anything by half, cut from the same bolt of cloth, at least in a sense, as Ellen Knox. She speaks in broad terms and thinks in big ideas, and the development within the faculty and the programs bear out that kind of leadership.

The instructional day

As with the Upper School, the instructional day starts at 8:20 and ends at 3:30. It begins with Prayers three times a week, though, again, that name is something of a misnomer. In practice, Prayers are assemblies, a chance for the student body to come together around an expression of the values of the school. Those values stem from the Anglican tradition, though are generalized somewhat and are more humanist in feel. While some hymns are sung—something that the students, in truth, seem to relish—the messages are keyed to the life of the school, from upcoming events, to guest speakers, to celebrations of individual achievement. Students have a chance to present during Prayers, which is an important aspect of both Prayers and the school culture.

Opportunities for involvement range from the informal, to suggestion boxes within the classrooms, to participation with the Student Institute Team (SIT). The SIT program is the Junior School component of what was previously known as the Institute, though is now more commonly described as the Forum for Change. Whatever the name, it’s an office designed to reinforce the values of the school, namely Integrity, Inquiry, Compassion, and Courage. The guiding question of the program is “what kind of world do you want?” and it’s one that students have answered in a myriad of ways.

The goal of the SIT office, as with the Forum for Change, is to allow girls to experience true agency. Rather than passively joining a club, or participating in an extracurricular program—both of which are options, too—they are able to advance project ideas, from raising funds for a cause to starting a student initiative. SIT meetings are held weekly, including a drop-in session every Wednesday morning through the school year. There, students share ideas in an open, supportive setting, and are then given support and, in many cases, the resources necessary to turn their ideas into action. The results are often impressive, not the least of which being the sense of agency that students gain through these experiences. It’s the precursor, if not a prerequisite, for what they’ll experience when they move on to the Middle and Senior School grades.

Program development

The feel of the facility is very modern, clearly up to date in terms of the integration of technology into classroom instruction. It’s all of a piece and feels recent, which for the most part it is. Nevertheless, the Junior School is also on the eve of a build, and is now in the midst of a significant capital campaign. The additions will continue the hub model, further integrating all of the curricular streams. “We aren’t moving away from what we already have,” says Dexter, “we’re expanding what we have.”

Included is a very welcome addition of a full kitchen and servery. Prior, meals were catered, and while healthy—they all reflected the same ideals of the Upper School kitchens—didn’t offer a broader interface beyond consumption. The new kitchen, to be opened in 2019, will provide opportunities for the junior students to get involved in food production and prep, and to learn more about where their food comes from. “We can get the girls involved in prepping the food,” says Rauni Whiteley, director of food services. “And you’ll find, with kids, the more you involve them in the choice of what they’re going to eat, or the preparation, they’re far happier to eat it than if we just put it in front of them and say ‘there you go.’”

The Junior School menu will be brought in line—both in terms of its breadth and variety—with that of the Upper School cafeteria. Less obvious, but also important, is the fact that in-house production will be greener, in keeping with the school’s environmental impact goals. Says interim head of the Junior School, Kate White, “The facilities are just going to allow us to build upon the great work that we’re already doing.”

Academic environment

“Our job as the adults in the building is to help them take risks and try some new things,” says Maggie Houston-White, “to figure out what they like and what they don’t like; what they’re good at and what they’re not good at. Sometimes what you love, you’re not good at. But that’s alright. Just do it.” The school prides itself on academic rigour, though beyond that, there is a keen attention to maintaining an environment in which the girls feel known and valued.

Throughout its long life, Havergal has been the kind of school that others have looked to as an example of progressive, socially responsible education. Knox danced to the beat of her own drum, and if there is one overriding tradition within the school, that’s precisely it. Garth Nichols, the vice principal of student engagement and experiential development, notes that “a lot of schools are Me to We schools, and we by design are not; a lot of schools are AP or IB, and we by design are not. And that’s because we firmly believe that we have a philosophy of education that is true, and that is strong.”

"We were drawn to Havergal really out of a quest for finding an environment that would be challenging"

—Roslyn Mounsey, parent

Nichols’ role—vice principal of student engagement and experiential development—is emblematic of the school’s approach. Most vice principal roles are cast within a hierarchy of administration, not development. “I think it really speaks to Havergal’s vision,” says Nichols, “that they’ve made this a vice principal role, and not a coordinator role or a director role. This is the voice at the table of innovation, bringing in something new that adds value.”

Similarly, Michael Simmonds is vice principal, school life, operations—again, not a role that is, at least in other institutions, so clearly defined. Those kinds of roles are telling of the culture of the school, as well as the ongoing development of the programs. School life, in other institutions, can easily be seen as secondary to the academic programs, in part because parents, when choosing a school, typically look to academics first. They’re right to, though the success of any school in the lives of the students that enroll there is an expression of more than just the approach to academics.

Simmonds says that, “when parents send their kids to this school, ultimately they’re sending them here, I believe, because it’s an excellent place for students to learn.” He’s also very quick to qualify that, noting that an excellent place for students to learn is one in which they feel that their passions are understood and shared, and where they are appreciated for the talents and perspectives they bring to the school community. He works to ensure that within the Havergal environment. “You will find yourself reflected someplace. And that’s what we celebrate in our community.”

“We were drawn to Havergal really out of a quest for finding an environment that would be challenging,” says parent Roslyn Mounsey. “[My daughter] had always excelled in school … [though] she was a bit under challenged” and not feeling a real push to reach her full potential.

That’s the impetus for many parents who look to Havergal: there is a sense that their daughters could be doing better, yet they find themselves in situations in which girls are left to settle with good enough, or are prevented from trying new things. “There’s no preconceived notions about being good enough. She puts herself forward,” says Katie Salem, mother of Nadia, now in Grade 9. “They have to be given the opportunity to take chances and to take risks and know that the school is there to support them.” Being a single-gender school is part of that. “I’m a huge advocate and believer in single-sex education because it’s so great for girls to have this unencumbered enthusiasm,” says Salem. “When I grew up it was almost shameful to be good in math because it was [seen as] a boy thing.”

“I felt like she fit in at Havergal, both in the physical environment and in the people environment. … she’s really found her place. … It’s the values system that she relates to. It’s more a sense of community, a sense of value, to abide by and adhere to.”

Both Mounsey and Salem are fairly typical of the parents we spoke with in that the sense of community soon takes a front seat in their appreciation of the school. “She’s made really good friends,” says Mounsey of her daughter Catharine. “We dropped her off this morning and she met up with one of her friends and I watched as they literally put their arms around each other’s shoulders. That’s the kind of strong bond and connection that makes us so happy that she’s there.”

Academics

“We have incredibly strong roots, because we’re really clear about who we are,” says Maggie Houston-White. “And those really strong roots allow us to go out on a limb and to be innovative.” The adoption of Harkness tables, when first introduced, was an example of that, as is a dedication to classroom technology. Instruction is focused around inquiry, and experiential learning, rather than didactic instruction. All of the courses are founded in big questions, and aligned as much as possible to the girls’ lived experiences and interests. Students are expected to come to class prepared to play an active role in discussion, encouraged to have a voice. Havergal provides a liberal arts education, namely one that intends not to educate students to the vocations, but to educate them to engage creatively, thoughtfully, and respectfully with the world around them.

An example is the Form Challenge, a program that provides a focus in the Middle School for five months of the year. For 75 minutes every Tuesday over the course of months, students work on a project based in their own interests. “There’s no specifications,” says Nichols, “but we lead them through design thinking protocols. For example, empathizing with your end user. Whether you’re making homemade lollipops, or you’re making jewellery to raise money for an organization you believe in, you empathize with the user: create it, design it, test it, iterate on it, and redesign it.” It’s innovative, and perhaps somewhat in contrast, if only superficially so, with the more traditional elements of school life.

In the Junior School particularly, the core curriculum is exactly what it should be, centred on facility with numeracy, literacy, and the social sciences. The delivery is progressive, collaborative, and inquiry based. Instruction is cross-curricular, conducted within the context of larger questions, and addressing big ideas. There is a dedication to creating authentic learning—connecting to the students’ curiosities both within the school and beyond—that is personal and student oriented. “It’s not an environment where there’s one way to learn,” says parent and chair of the Board of Governors, Martha Simmons. “Each girl is encouraged in their own way … and going to be taught in the way that she learns best.”

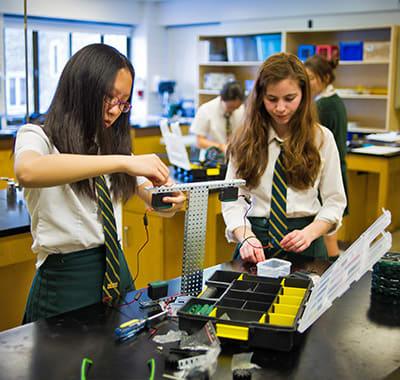

There is a full menu of specialty offerings, from dance to French to coding. There is also an ongoing development of the STEM program, with the goal of stimulating a genuine experience and interest in science, technology, and engineering.

Global opportunities

The Forum for Change is a project unique to Havergal, an office tasked with helping students work collaboratively with faculty and staff to help connect them to the world outside of the classroom. The Forum for Change grew out of the Institute at Havergal, created in 2006 as a means of restating the school’s commitment to informed, empathetic global citizenship.

“This place was founded as the [school] mission in action, the mission being to prepare women to make a difference,” says Melanie Belore, manager of the Forum for Change. “There was a need for a space to really live that mission within the school.” Initially called the Institute at Havergal, the name was recast by students, and is now known generally as the Forum for Change.

Many schools have programs related to community service. The goal is, as the term implies, service: providing assistance within local and international communities. Building schools, digging wells … the model was adopted with verve in the 1980s, though there were imperfections that, in many instances, are quite keenly felt today. Prime among them is the sense of paternalism that international service can unwittingly imply, rather than growing a sense of shared involvement.

Via the Forum for Change, Havergal has taken the things that make those programs important—community outreach, empathetic engagement—and has come at them from a notably different, entirely fresh angle, one that no doubt other schools will choose to follow. At its simplest, the Forum for Change is an office in the school where students can pitch ideas for projects they’d like to participate within or initiate.

The thinnest edge of the wedge is community service and volunteerism, something that has been built into the Ontario high school graduation requirements. The Students Act Now program is Havergal’s take on local service learning. Students have opportunities to work with local partner organizations. Global Experiences is the international travel, cultural immersion piece. The Forum for Change is the next step, in a sense, bringing the learning goals even further forward, and allowing students to build ideas of their own, rather than only applying their efforts to existing programs. The AIM Sport for Community Camp is an example—it’s a direct result of students coming forward with an idea for a camp, and it’s been running two sessions each summer ever since.

The goals are focused rightly on the students themselves, seeking to expose them to the perspectives of others, provide opportunities for real-world collaboration, build community partnerships, and provide an authentic understanding of the students’ place within a social context, locally and globally. Not all ideas reach fruition, but even just talking about them, and having them taken seriously by a member of the staff, is a valuable experience. Many ideas do indeed reach fruition, with the staff of the Forum providing guidance, tools, and seed funding. It’s also the entry point to two signature programs, the Global Experience and Students Act Now.

Food services

In more ways than you might imagine—and, truly, you may not imagine all that much—the meal program is emblematic of the school itself. The school takes nothing as writ, and food service is no exception. “We really like to think that our food program is one of the differentiating points of Havergal,” says Rauni Whiteley, director of food services. “Because it’s not just getting something on the plate and feeding people. There’s more to it than that.”

Whiteley gained a wealth of industry experience before arriving at Havergal, including as a director of catering at the Royal Ontario Museum. For her, food service isn’t just about nutrition—it’s also an opportunity to learn about food, culture, business, and health.

“I think it’s important because food is critical to everybody’s well-being. ... A fueled mind is a strong mind." She adds, "For the girls, food is becoming quite political these days, and there are some good reasons to start a dialogue around food. You ask the little ones ‘where does food come from?’ and they say Sobeys. I really want our girls to be able to make the connection between the farmers and where the food’s coming from.”

Whiteley takes food service into the classrooms, presenting on a range of topics, including the business of food, production, and agriculture. It’s because of her work with the students that, when you ask about the dining hall, you’ll not only hear about how great the cookies are, but also the triple bottom line.

“We really just want the girls to have a healthy dialogue around food,” including why it is important to support local producers, or why it is important to enjoy Ontario asparagus when it’s in season. “If you can say to the students, ‘I met the farmer that raised this beef’—to make those personal connections, instead of it just being a truck, where stuff just comes off the back.” And indeed, she regularly does precisely that. Whiteley says, “we are in the business of feeding minds.”

Pastoral care

Wellness programs are rich and broad, and a dedication to wellness in all areas of student life is clear and demonstrated. Havergal refers to the “circle of care,” the centre of which is the guidance office. Physically, it is a suite of offices centrally located—students regularly pass by the office and, as they do, are encouraged to stop in. In the lobby is a table with a jigsaw puzzle continually on the go. Just as continually, there are a few girls around it, working the puzzle and otherwise taking a break from the stream of life outside the office doors.

It’s telling of the program that the guidance offices are that inviting, and that central within the students’ lives. It’s been crafted to be a location within the geography of daily life, not somewhere hived off, there for those who need it and otherwise unseen. The message is subtle, but it’s understood: if you need a place to cool your jets, chat about anything at all, or just sit at the puzzle, we’re here.

Certainly, how a guidance faculty presents itself, and how it posits itself in relation to the student body, is central to its effectiveness, and by all measures the guidance staff is very effective. “As guidance counsellors,” says Heather Johnstone, head of guidance, “our goal is to know the students, their academic needs, interests and skills, and to advocate for them. We help them figure out who they are as learners, guide them on the pathway to achieving whatever goals they have set for themselves and help them navigate their social-emotional needs.”

Johnstone notes that it’s perhaps more typical for schools to divide academic counselling from emotional and social, though at Havergal they’ve opted to keep things centralized within a single office and a single staff. “To be honest, university counselling is wrapped in with all of those other things, particularly for girls.”

Also within the circle of care is an on-site nurse and a chaplain. A social worker, Angie Holstein, is on campus three days a week, and during that time is dedicated to serving the Havergal community. She provides intervention when kids present with mental health challenges, as well as working in the classroom to promote health and wellness, including destigmatizing mental health interventions. She’s part of a team tasked not only with intervention, but also awareness and prevention.

There’s a lot of pressure within independent schooling, which can be encouraging in many ways, though it is also something that students need to be able to manage effectively. “Besides the beauty of the grounds, it provides a lot of unique opportunities for kids,” says Holstein. “But it’s challenging for kids, too, because they’re within an environment where everyone is high achieving. So how are they able to be special? How do they achieve something that’s memorable?” It’s encouraging that those kinds of questions reside at the core of the delivery of care. All reports are that delivery is consistent and applied, as indeed it should be, in a very student-led way.

The path to care at times is direct, with a student approaching either the counselling office or the social worker. More typical—within the school, as in life—it’s indirect. “The teaching faculty here is probably the strongest I have seen in terms of commitment to students,” says Johnstone. “The teachers know the kids. So, many times, the work we do in this office is flagged by teachers. ‘Can you check in on so-and-so?'” The teacher-to-student ratio is good for instruction, though it’s also good for that interface.

“You will waste your mental efficiency if you specialize too early, just as you will waste your physical efficiency if you indulge too frequently in lobster salad and pickles.”

—Ellen Mary Knox, founding principal

Every story is unique, and there’s attention to that too. “Kids struggle to make connections, because high school is hard,” says Johnstone. Support, she believes, needs to start from that point. “We have a ton of introverts in an environment where we foster leadership. We can’t all be leaders. … it’s well documented in the literature that we need to do more around interrupting patterns of anxiety and perfectionism. Because the cost of that is collaboration. [We need to look] at the long-term skills of these girls, and if everyone is a leader, it’s hard to collaborate.”

There’s a great honesty, too, around the challenges that the school faces, and the realities of student life. Says Maggie Houston-White, “People think that, you know, I’m going to send my kid to independent school and it’s going to be sunshine and lollipops. It’s not. But when you’re having a day that’s not so great, you want it to be in the school that you want to be in. You want it to be your community, and it makes that day that much better.” To be sure, it’s a great approach, and is, by all accounts, matched by the delivery of care.

Mental health is, rightly, a focus—something that the school doesn’t take lightly. Its dedication is evident in a number of ways, one of them being a partnership with Jack.org.

Getting in

The program is as much about character as it is about values, and the admissions process is designed to find the right students. Maggie Houston-White, the executive director of enrollment management, says that the admissions team is looking for students and families who understand what Havergal is all about, “who are committed to educating their daughters, but also understanding that there are so many possibilities for them.” Academics are important, of course, as the program is rigorous. “Number one, you have to be academically capable here.”

Beyond that, says Houston-White, “We’re going to look at them as people. Kids who are going to be engaged in the breadth of the program.” That’s gauged principally through an interview. Houston-White is clear that it’s a conversation, not a test. “When we’re in an interview—and we say this to the kids—we’re not looking for that gotcha moment, we’re not looking for why you shouldn’t come to Havergal. Our job is to find out why you should come. … [whether] they going to be engaged in the life of the school.”

Parents interested in enrolling their children are strongly encouraged to visit the school, either by appointment or at the open house events hosted at the school in the fall. Those wishing to enroll are asked to complete an online form and to pay an application fee. The deadline for completion of the online form and payment of the fee is December 1.

All candidates are required to complete a written test as part of their application package. Students entering Grade 7 are asked to write the Havergal Critical Competencies & Character Assessment for Grade 7 candidates. It is given at the school in early December of each year. Students unable to travel to the school to sit the assessment are asked to complete the Secondary School Admission Test (SSAT).

Grade 8 to 11 applicants must write the SSAT, and the deadline for completion is in late January of each year. While the school welcomes foreign students, there is no ESL program. Students for whom English is not a first language may be asked to demonstrate fluency, often through completion of the IELTS test.

Money matters

Tuition is on par with that of other like institutions offering a similar breadth of programming. There is a financial aid package, and 7% of the students are beneficiaries of it. Aid is granted in the form of bursaries, with the aim to continue to move toward barrier-free admission, where finances aren’t an obstacle for mission-appropriate students. Like most schools, the application of financial aid is needs-blind, and is handled through a third party. “For me, whether you need financial aid or not has nothing to do with your admissibility to the school and our process,” says Maggie Houston-White. Families that have applied for financial aid will receive, along with the offer of admission, a separate letter from Havergal’s CFO indicating the aid offered.

Parents and alumni

Parents report a high satisfaction with the school, often citing outreach. “It is important for our girls to see their parents involved in the school,” says Laurie Hay, past chair of the Havergal College Parent Association (HCPA). “When they see us taking on leadership roles and acting as ambassadors, our kids lose the perception of the school as a separate entity from their home lives. It helps them connect with the school on a different level.”

There are roughly 8,000 Old Girls, and they are very welcome to participate in the ongoing life of the school. Teas are held in the fall and spring of each year. Alumni also take roles in school governance. The Havergal Old Girls’ Association (HOGA) was established in 1920. Its forerunner, quaintly, was a book club: the Coverley Club. HOGA, frankly, is one of the best examples of alumni engagement you might ever hope to find, and the level of engagement with alumni is both broad and brisk. The archivist, Debra Latcham, regularly receives packages of memorabilia from Old Girls, and they tend to pile on the floor around her desk until she’s able to get them into the archives proper. All of it is charming, and packages include handwritten notes, report cards, as well as inscribed copies of Ellen Mary Knox’s books.

Notable alumni aren’t always the best means of gauging the success of a school or its academic culture though, in Havergal’s case, there are some strong hints. There are a lot of firsts on the list. Christine Coutts Clement, an astronomer, was the first Canadian female to discover a supernova. Margaret Norrie McCain became the first female Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick. Gail and Karen Johnson became the first women to represent Canada in Olympic sailing. Jane Poulson became Canada’s first blind physician. Gillian Hawker became the first female chair of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto. Gillian Apps won three Olympic gold medals as a member of the Canadian women’s hockey team.

In keeping with Knox’s original vision, graduates have gone on to become national leaders, creating opportunities for women, and providing strong role models for others to follow. Dora Mavor Moore went here, as did Linda Frum and Carolyn Bennett. Paula Cox was elected Premier of Bermuda in 2010. Kirby Chown advocated for women in the legal profession.

The arts are represented, too. Jane Urquhart, Margot Kidder, and Carol Welsman are Old Girls, as is Mariko Tamaki, who was shortlisted for the 2008 Governor General’s Literary Award for her graphic novel Skim.

The takeaway

While the earliest boys’ schools in Canada were created to extend the traditions of Britain, the earliest girls’ schools were created to chart new educational territory and new opportunities for women. They were led by women who were themselves at the leading edge of women’s rights, even before we had that term. The goal was to allow women to gain a voice, and to move into positions of authority in academics and beyond.

“Girls leave their time here with a unique tone in their voice: confidence.”

Havergal is an example of all of that and has continued in the same vein ever since it was founded in 1894. While the world has changed, the initial goal remains: to allow girls to take risks in a safe setting, and to encourage them to grow into a clear understanding of their strengths and their talents. The programs are designed to meet the girls where they are, and then to take them further, using their natural curiosity as a guide. Science is a focus, as it should be, though social engagement is as well. Teaching is forward looking, as it always has been at Havergal, and hews closely to the traditions of the school. There are many reasons why this is one of the foremost schools in the country: It’s an educational environment like none other, charting its success against itself rather than that of others. Havergal is also the kind of school that teachers look to teaching within, because of the challenges that the environment provides, but also the opportunities. “We’re continually looking to be the best Havergal we can be,” says Maggie Houston-White (an administrator who is also a parent of the school), “and I think that allows us to be such an incredible school.”

That thought is shared seemingly unanimously by the parents of the school as well as the alumni. Girls leave their time here with a unique tone in their voice: confidence. It’s a result of what they’ve found within themselves, as supported by the community they have grown within. Yes, they’re prepared for success at university, though the school sees that only as the beginning of its work, not the end. The project isn’t just about academics, but educating girls—just as Ellen Mary Knox proposed when she founded the school—to make a difference in the world. And they do.

Photography supplied by Havergal College