Holy Name of Mary College School THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Holy Name of Mary College School, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Introduction

Holy Name of Mary College School isn’t as old as it may appear, and there are some unique reasons for that. Many aspects of the school certainly aren’t new, including the campus itself (which was established in 1964), and all the buildings on site date to that time. Likewise, it has always been a Catholic girls’ school, and the Felician Sisters who founded it have been present throughout. The name, too, has been the same through the majority of the school’s life.

That said, the road from 1964 to now has had a few twists and turns, including a long period in which the school partnered with the Dufferin Peel Separate School Board. In 2008 wishing to continue their rich tradition in education, the Felician Sisters partnered with the Basilian Fathers of St. Michael’s College School in Toronto to re-establish the school as a private Catholic school for girls, combining the highest quality of education with a strong moral grounding in the Catholic faith, its traditions and worldview. It was a bold move, to be sure. While the student population under the publicly funded board was in the hundreds, the first year of the current school welcomed just 38 students, a new administrative structure, and new administrators and faculty. The new school would attract families and students that would actively choose the program based on an understanding of its strengths, while also authentically sharing the values and charisms of the governing orders.

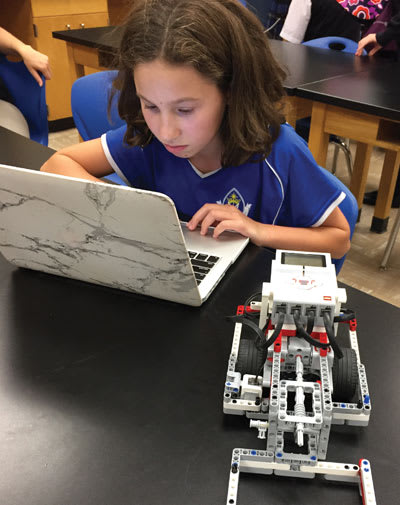

As a result, in all meaningful ways, it truly is a new school, comprising a new approach and a new lease on life. “Because we’re new, we’re constantly evolving,” says Marilena Tesoro, the head of school, “and so everything we do each year, through that process of continuous improvement, is intended to meet the needs of the modern girl in the context of our core values.” In the last few years, for example, they’ve added the Robotics and Innovation programs, something that Tesoro sees as emblematic of how the school will continue to develop. “I see that evolution as change based on what the needs are.”

The school defies many expectations of those who arrive with only a general sense—or a clichéd sense—of what is happening there.. “I think they expect it to be very traditional,” says Giselle Fernandes. “And when they come in they see how modern, how forward thinking it is. That we’re willing to work with girls, as individuals, and [help] them succeed.” The traditions are key to the life of the school, but redesigned to make everything very relatable and accessible.

Key words for Holy Name of Mary College School: Values. Inspiration. Excellence.

Basics

Holy Name of Mary College School is an independent day school for girls in Mississauga, Ontario. It offers a liberal arts education inflected with the values of the Catholic faith. The school is, at its heart, an expression of the Felician Sisters of St. Francis, an order which shares a campus with the school and the Basilian Fathers of St. Michael’s College School. Holy Name offers Grades 5 through 12, divided between a middle school and a senior school, with the guiding intention to prepare girls for success at university while also empowering them to leadership roles in science, entrepreneurship, the arts, and community service.

The academic program is progressive, hands on, and project oriented, and includes a dedication to STEAM, an emphasis on 21st century competencies, and a desire to look to the future, with a particular eye to fields in which women have historically been underrepresented.

The campus sits in the middle of a long stretch of Mississauga Road that meanders through an area of large, established residential properties, anchored at one end by the bucolic Mississauga Golf and Country Club. All the buildings on the property are set back from the road on a 25-acre site, and, if not for the signs and the flags, the campus would be very easy to miss. “You can’t really see the school as you go along Mississauga Road,” says Tesoro. “People sometimes say that they didn’t even know that we existed here, back behind the trees.” That’s perhaps the downside, though the corollary is a very big upside: the seclusion lends a lovely feel to the campus, an awareness of being set apart, allowing students to concentrate on the work of the school and be free from the distractions of urban life. It’s a unique asset, particularly given that the school is located within the largest urban area in the country. The QEW is just to the south, funneling commuter traffic in and out of Toronto, and otherwise the school is surrounded by the activity of a major suburb of a major city. On campus, though, is a sense of being a world away from all of that. The property includes the campus buildings, the convent, and a wealth of multi-use green space, from forest—students regularly see deer on the grounds—to athletics facilities, to an apple orchard that abuts the parking lot. The orchard is tended by the Felician Sisters, who use a portion of the apples to make cider each year, which they give out to members of the school community. In all of that, when on site it’s hard to believe that the urban sprawl of Mississauga, Etobicoke, and Toronto isn’t all that far away.

The buildings all date to the initial development, so there is a consistent, cohesive feel to the campus. The main building houses all of the spaces associated with student life. The convent operates largely on its own, but has intergenerational connections with the life of the school.

The façade of the school is an example of 1960s modernism: a box with windows, void of ornamentation. The interior spaces, by contrast, are wholly memorable and for all the right reasons. Instructional spaces are ample, inviting, and filled with natural light. Shared spaces, including the cafeteria, invite a sense of calm, thanks in part to ample interfaces with the grounds outside. The Chapel has the same straight lines as the rest of the school—the stations of the cross are square tiles in keeping with the dimensions and feel of the room—which perhaps belies the charm of the space, dominated by a stained glass window along the south-west facing wall. It’s arresting, again, in all the right ways. The feel that the window lends is one of calm, bathing the room in yellows and greens. It’s a highlight of the campus, in part because it was constructed by hand—one piece of polished glass at a time—by Sr. Colette Michniewicz, former art teacher at Holy Name, and helped by other Sisters and students. The window and the chapel it sits within are a vibrant part of the school and provides an analogy for the culture of the school, with all kinds of lovely overtones: life lived in service, the sense of a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, the strength of the extended community, and an air of peaceful, reasoned reflection.

Leadership

Holy Name is overseen by a board of governors, with members approved by the Basilian Fathers and the Felician Sisters orders that sponsor the school. “We’re probably the only school, maybe globally” says Tesoro, “that has two religious orders that serve as its foundation.” Tesoro was appointed head of school in 2011 and has worked in both public and private settings as well as at the Ministry of Education. One of the things that drew her to Holy Name was its independence and the agility that comes from reporting directly to a board of directors. “You’re able to make great things work,” she says, “because you’re entrusted with that responsibility.”

She is the kind of leader who is visible, and approachable, by all members of the school community, from students, to faculty and staff, to the parent population. She appears to know the students well—not merely their names, but also a sense of where they’re coming from and where they’re headed. She approaches all with a warm smile and a hello, and is invariably greeted in kind. She can take a joke as easily as she makes one. While she’s the driver of program development, she is also engaged with the culture of the school and works to promote an amiable, collegial atmosphere throughout.

Background

The campus was founded in 1964 as the Holy Name of Mary School, a private institution created as an expression of the Felician Sisters, and to grant a focal point for their work in Ontario. The school began to receive public funding in 1972, and by 1987 it was funded entirely by the public board. In 2008 the Sisters decided to return the school to its roots, co-founding the independent Holy Name of Mary College School. As such, it became what it is today, namely Ontario’s only independent Catholic school for girls in Grades 5 to 12. It shares a formal association with St. Michael’s College School, the largest Roman Catholic boys’ day school in Canada.

In the 1960s and the decades that followed, the Sisters ran the school. “They were the teachers, the administrative staff, the cooks, the cleaners,” says Tesoro. “They took on every aspect of the school.” In the early years, there was a boarding program, and the Sisters ran that, too. ‘Today, they are actively involved at the Board level and in various collaborative initiatives. Their presence, though, is keenly felt, and girls visit them regularly. “They have tea, they chat, they have pen pals. Sometimes they help them make crafts for the mission store or volunteer at St. Felix Centre.”

Their presence provides an ongoing reminder of the charisms that inflect the delivery of the curriculum. “Mission integration is pivotal to everything we do,” says Tesoro. “We integrate it into the religion classes, so there are strategic inserts from Grade 5 all the way to Grade 12, in terms of what they’re learning about those values and those charisms. We’re basically an extension of the [Felician Sisters’] hands. Although they can’t physically be here, they are actively involved through the mission integration that happens. The same is true of the Basilian Fathers.” The Basilians are remote—they aren’t physically on the property so aren’t a part of everyday life on campus—but a representative serves on the Board and they assist throughout the year in the celebration of the Eucharist and the sacrament of Reconciliation.

The Basilians are known for their active promotion of academic excellence, while the Felician order integrates the values of social responsibility and compassion. Those interests form the basis for the delivery of the curriculum, and most of the families, rightly, are attracted to the school because of those values and the community that has formed around them.

The Felician Sisters

The Felician order was founded in Poland by Mary Angela Truszkowska (born Sophia Camille Truszkowska). She valued education, and while convalescing after contracting tuberculosis, made use of her father’s extensive library, exercising a particular interest in philosophy, ethics, and social thought. She founded the Felician order as one of active contemplation, a focus that was atypical for the time. Prior, female orders were cloistered, and while Mary Angela considered joining an existing order, she decided instead to found one based in active involvement within the community. In 1855 she established a home in Warsaw for homeless women and girls, whom she gathered from the streets of the city.

The Felicians first established missions in North America in 1874, and initially sought to support women within the Polish community, with education as a primary focus, as well as ministering to the poor. Their work has broadened since then, and missions have been created in the United States and Canada. Then as now, the activity of the order reflects the things that Mary Angela valued in her own life and sought to promote: intellectual curiosity, excellence, empathy, religious contemplation, and lives lived in active service.

The Basilian Fathers

The Basilian Fathers were established as a religious congregation in France in 1822 in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Their work was focused in educational and pastoral care, work that took the order to Canada, the United States, Mexico, and Columbia, where they remain active today. They opened St. Michael’s College in 1852, offering, in the French style, a combination of high-school and university education.

Academics

The academic program was initially modeled on St. Michael’s College School, and, as there, the curriculum is accredited by the archdiocese and the Institute for Catholic Education. The school is committed to the integration of 21st century skills and the development of each girl’s love of learning. The curriculum is tailored for girls who are given every opportunity to develop and excel in the way they learn best. Grades 5 through 8 are delivered as a means of preparing students for the high-school years. Course work is rigorous, and the pace of delivery accelerated, though within a culture of achievement and support. Students graduate with the Ontario Secondary School Diploma.

“There’s a real trust in the basics,” says Kristin Prillo, who has been teaching at the school for almost a decade. “You need to know your times tables,” she says, though noting that, nevertheless, there is a lot of discussion, and room for discussion, within the classroom setting. Instruction is collaborative, and classroom space is structured to invite a range of engagement. Kaitlin Soscia has been building the business program for the past six years, bringing in modular seating and whiteboards that circle the room. There are window writers, too, extending the whiteboards and allowing girls to present their ideas to the class, in real time, as they go. Anchor walls—dedicated whiteboards—allow girls to keep track of various projects over longer periods of time. “I just started thinking outside the box,” says Soscia, “and not being locked into your usual position” of the teacher as an expert lecturer, with students passively taking it all in.

Throughout the school, learning is inquiry-based, and faculty is encouraged to look beyond the campus for instructional and experiential opportunities, all of which effectively expand the campus and the programs, often into real-world settings. There is a growing relationship with University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM), with girls visiting to attend lectures, participate in forensic science labs, and make use of the athletics facilities. In time, all going well, Tesoro intends to include opportunities for high school students to attend university courses at that campus.

Instructional development is based in bi-weekly meetings of the staff. Staff members are encouraged to find avenues to develop their programming beyond the base level curriculum requirements and with an eye to student collaboration. “We’ve worked through a couple of years of really helping the teachers change the way they deliver the program,” says Tesoro, “using technology but also not being the disseminators of knowledge, but instead facilitating the learning. We want to get them to really embrace that feeling of not knowing everything, and give autonomy to students, through project-based learning, to really excel.”

Development initiatives include third parties, such as the Future Design School, which was consulted on the Innovation Time program as well as other 21st century literacy and learning initiatives. “If we have staff who would like development in their fields of study,” says Kathryn Anderson, director of schools, “they engage with professional groups outside of the school to maintain the things to be working on, making sure they’re aligned with where the ministry is headed.” Indeed, the staff is demonstrably adept at reaching beyond the school walls to neighboring institutions. And the parent community, says Anderson, is seen as a resource as well, either coming into the school to speak with students, or networking out to professional and philanthropic organizations in Mississauga and beyond.

“We’re always thinking five to ten years out, always looking ahead in our strategic planning. We want[ed] to look at how education was changing, and how it wasn’t meeting the needs of the employment opportunities that were quickly changing.” In an awareness of a changing workplace, the guiding question, says Tesoro, is “how do you bring them there? You have to change, and the biggest change has to come from the teachers.” That’s refreshing to hear anywhere, though perhaps even more so within a school that, while young, is representative of a very established tradition.

“I think it’s all about iterations,” says Anderson. “As teachers we should always be thinking about what’s next. And that’s really what we’re teaching the kids to do. ‘Yeah, you’ve done this project, but there’s probably ten things that went wrong. If we gave you the same project again, what would you do differently, and how would you approach it differently?’ And I think that’s the mindset that the world is looking for. There’s no static job that you’re going to have for your whole career. Everything is evolving, and you have to have the confidence to find what the next opportunity might be, and then seize the day and go with it. … [It’s important] to be adaptable, to be one of those people who is flexible in a work environment.”

As a means of supporting the development of the programs, faculty are tasked to create annual learning plans that are informed, uniquely, by a student feedback survey completed by enrolled students in early November of each year. “You have a student sitting in your class for one or two months,” says Tesoro, “and you want to know what they’re thinking.” In the survey, students offer their thoughts on classroom management, content, pace, and instruction style. “It may sound like a negative,” admits Anderson, “but the comments are actually very validating.” The feedback helps to form the teaching goals for the year while also granting a sense of agency and involvement on the part of the students. The survey, for both faculty and students, provides a cornerstone of that relationship. Students are encouraged to be very active learners, making demands of their teachers, and intentionally building on their curiosities, while the faculty continue to bring them forward within the classroom and co-curricular settings.

“It’s about flexibility,” says Tesoro. “We know that the educational system is based on a 200-year-old model where you learned math, and you learned geography, and you went from class to class and there was no cross-pollination and no cross-curriculars. So we’ve introduced one day—it’s 140 minutes each Thursday—where they get to problem solve and look at things in varying perspectives and are on a quest of discovery, to expand design thinking.” Girls work collaboratively with each other in areas of shared interest. The work ranges from creating a fiction and arts anthology, to technology, to one group of girls that designed a new cosmetic line. “They even 3D printed the containers they go in,” says Tesoro. “So there’s a lot of chemistry [and] arts, and they get to connect with real-world applications to either improve something, or innovate something new.”

The projects are tied to the various disciplines involved, so a nice added benefit is that the faculty find new and often unexpected opportunities to program together. This kind of thing isn’t unique to Holy Name—indeed, there are examples of similar programs at other schools—though being in this environment, namely all-girls with a signature constellation of values, brings a unique flavour. Says Tesoro: “Creativity spawns innovation, and that’s what we want. And we’ve been able to collapse some of the course work and really get people working together.”

The faculty that we met are true go-getters, including Euginia Nicoletti, who teaches science. “She really goes into it,” says Senna, a student completing Grade 11. “You can tell that she really likes to teach the subject, and it helps you connect to it. It’s not like you have to learn it, but you’re interested in learning it.”

Nicoletti seems particularly adept at finding authentic learning experiences, and bringing her experience of industry—something she gained prior to entering teaching—into the classroom. This past year she partnered with Amgen and UTM. “I brought second- and third-year university biolabs into our school. I was exposing students to post-secondary experiences like micro-pipetting and loading gel plates and they were excited for the opportunity. We also did some recombinant DNA cuts and made a recombinant plasma which was a little over their heads,” she admits (and frankly, it was over ours, too). While she spoke to us, what she was really communicating was her excitement and interest in science, something she no doubt communicates to her students as well. It’s not a mystery why girls from Holy Name have placed in the top 10% out of more than 4,000 high-school students for the past two years at the Avogadro Exam held each year at the University of Waterloo. They see science as truly worthy of their interest, and they are compelled to get involved.

Similarly, girls are able to take part in Destination Imagination, an annual STEAM-based challenge. Teams are challenged to write a script and solve a scientific challenge in under eight minutes.

And they do. In Ontario, Holy Name placed first, second, and third in various categories in 2017–18. The girls went on to compete at an event at the University of Tennessee, attended by 17,000 like-minded students from across North America and around the world.

In recent years, roughly two-thirds of the graduates have gone on to math, science, and engineering and technology programs at university. “This is completely against the norm of what you would find traditionally,” says Tesoro, something she credits to immersing girls in activities that may be new to them, as well as the opportunities that an all-girls’ environment necessarily provides. But, it also doesn’t just happen. Events like the Engineering Career Night, launched by the Robotics Club mentored by physics teacher Dr. Karen Kozma, brings engineers, both men and women, in to speak informally with students about what they do. It cements the idea that these careers are options—and very real options—for them. Kozma, who is a professional engineer and an alum of the original Holy Name said “In this setting, girls are allowed to discover their natural potential in non-traditional fields. They bring a unique perspective to STEM.

The academic environment

A recent alumnus said that, on arriving at the school from a coed environment, “I thought, ‘Okay, I need to step up my game.’ I saw everybody was doing good and I thought, ‘I need to join them.’” And she did. She credits HNMCS with giving her the drive to get the marks and the experience she needed to get into McGill and succeed in that environment. A culture of achievement informs the programs at the school, effectively creating the rising tide that lifts all ships.

A rich and close interface between faculty and students allows for a range of learning supports, both formal and informal. “She was getting Bs, doing fairly well, not getting in trouble,” says one parent f her experience within a public school setting. She was part of the “invisible middle,” something which that parent said doesn’t seem to exist at Holy Name. She is seen and heard, and her energies are channelled into positive activities.

The Elite Athlete/Artist program

Hanna Henderson (’20) won 11 medals at the 2017 Canada Summer Games, becoming the most decorated athlete in the history of the competition.

The Elite Athlete/Artist program was launched in the 2015–16 academic year to recognize the need for flexibility within student schedules and to accommodate students who are achieving success in those areas outside of the school. Advisors are tasked with ensuring that those students are able to attend rehearsals, competitions, and coaching in consort with their academic work. A prime example is Hanna Henderson, who, in addition to her academic work at Holy Name, in 2017 became the most decorated athlete in the history of the Canada Summer Games. “We want to support students as they strive for excellence in their athletic and artistic passions outside of school, while allowing them to achieve strong academic grades and personal balance,” says Tesoro.

Pilar Bianchini, a competitive dancer who trains 25 to 30 hours each week, says that the Elite Athlete Program “has been very supportive of my demanding training schedule while providing me with great academic opportunities.” Says her mother, Lori, “One of the best aspects of this program is that a point person meets with our daughter on a regular basis to discuss her school work and her wellbeing. There is a lot of flexibility to move assignments and tests to accommodate her training and reduce her stress levels.”

The instructional day

Each day begins with a morning reflection based in current events and through messages that are written by the students. While the values promoted during the morning message relate to those of the Catholic Church and the charisms of the two orders that inform the life of the school, the messages themselves are, for the most part, secular.

Mondays alternate between a teacher/advisor program one week and Motion Monday the next. As the name suggests, Motion Mondays are about light exercise, which can range from a brisk walk to a lacrosse lesson or meditations before the start of the academic day.

In Grades 5 through 8, students engage in co-curricular activities from 2:30 to 3:30 p.m. on Monday, Wednesday, and Thursday. In the senior school co-curriculars are scheduled Monday to Wednesday, and on Thursdays they are involved in Innovation Time. Co-curriculars include sports, teams, and clubs, the guiding principle being challenge by choice.

On Fridays there is a dedicated chapel period, which can range from guided discussion, to student presentations, to an outside speaker addressing a topic of interest. Topics are rooted in the values of the school and tend to be big, such as community connectedness, mental health, and environmental stewardship. Mass is held one Friday each month, presided over by one of the Basilian fathers or a priest from the local community.

Global learning

Global mission trips are mounted each year, including participation in construction projects and medical clinics. Apart from teaching science, Euginia Nicoletti is a trained pharmacist, has worked in the industry, and brings all her experience to her leadership of the global mission program. In some instances, she has worked alongside local health care workers, creating an opportunity to get the girls involved in actual, working care settings. “I’m the pharmacist when I’m there,” she says, which is something that grants the students a front row seat to some of the complications of administering care. “I show them how to make antibiotic suspensions, and show them how, in the third world, we’re not in sterile conditions. So they get a sense of how things are run in the third world,” including an understanding of how relatively simple interventions can become difficult or complicated. On each trip, they do two days of builds, such as building retaining walls or taking part in construction projects; two days of clinics; and some traditional mission work, such as delivering Sunday school classes.

In 2018, students travelled to the Galapagos, the Amazon, India, and New York and benefit from experiential learning opportunities. The global programme is intended as a continuation of what’s going on in the classroom: developing the skills, attitudes and behaviors necessary to succeed in an increasingly globalized marketplace. In, the girls get involved in specific projects that are as important as the experience of travel itself, if not more so. “We were helping the scientists collect data through fish, herpetofauna, cave, bird, and mammal surveys,” says a student who participated on a trip to Croatia. “It was so exciting to be part of real life scientific research, that I would even sign up for extra activities, like a bird survey at night.”

Student population

The student population was renewed in 2008, and ever since, it has been comprised of girls attending the school for its merits alone, as opposed to a student population based on board catchment guidelines. Enrolment rose quickly to where it sits now, just shy of 225 students. Says Tesoro: “As one of the only all-girls’ schools in the province of Ontario, it’s incumbent on us to help girls from all different parishes. We span pretty much all of the GTA.” As such, the catchment area is considerably larger than most other schools in the region, and the school is serviced by nine buses that draw students daily from as far away as Georgetown to the north, Milton and Oakville to the west, and Richmond Hill, Kleinburg, and Vaughan to the east. Routes are planned to be efficient, avoiding as much of the commuter traffic as possible. For example, the bus from Richmond Hill takes Highway 407, making the trip in 45 minutes.

While all students are welcome, for the most part they share a religious heritage, and many of the families that enroll are drawn by the expression of Catholic values within the life of the school. Not all of the students who attend are Catholic, though a majority are, and all have some relationship to Christian life. “Everything we do here is really rooted in the gospel values and the life of Jesus, so you really have to embrace that,” says Tesoro. “Our focus is on the core value of Respect, Compassion, Justice and Empathy and families come here for that moral grounding.” All students are expected to participate in the religious life of the school.

Tesoro is a great proponent of girls’ education and speaks about what the environment can provide with a palpable enthusiasm. Often, girls’ schools speak to issues of distraction—that in a single-gender environment, they are free from the distractions that occur within a coed environment—with the assumption being that girls are distractible. Tesoro, refreshingly, doesn’t speak in those terms. For her, these are girls that are talented, goal-oriented, and absolutely capable. She feels the greatest benefit of an all-girls’ environment are the unique mentorship opportunities that it provides. “Every leadership role in the school is held by a girl, so then the role models are there.”

Students clearly appreciate that focus. Entering the school population means entering a community of like-minded peers, all of whom share similar aspirations and a dedication to achieving them. “Everybody is more goal-oriented here,” says a Grade 11 student who arrived from the public system. “And since we’re so small, I know the majority of people at this school. So the environment is very different.”

Prillo notes that the single-gender atmosphere opens up the experience the girls have with one another. “They speak differently with girls than they do when it’s girls and boys,” she says. She feels there’s a greater openness based in a higher level of comfort, perhaps. The mother of two boys is quick to note that she doesn’t mean to sound derisive. “I love my boys, don’t get me wrong,” though she knows from personal and professional experience that there are clear benefits to an all-girls environment, or, more generally, a single-gender environment.

The student population is divided into four houses, each named after a star in the sky. Girls are assigned to a house when they enter the school, and remain within that house until they graduate. As such, the houses allow for interactions between grades and support meaningful mentorship initiatives that might not otherwise occur. It’s very much a collaborative environment, structured to grant a sense of belonging, “because girls are very sensitive about that,” says Tesoro. “They’re pleasers; they want to be able to be connected to each other. They have that social need, and they’re highly sensitive. They’re self-doubters; they may not be natural risk takers. So that’s what we’re trying to do: get them to stretch themselves, and to take some calculated risks.”

Outdoor education programs allow students to try new things, take calculated risks, and grow leadership skills. In-school student leadership opportunities are rich and varied, and every girl assumes a leadership role of some kind, ranging from student president, to grade and subject area reps, to student life leaders, to positions within campus ministry, to subject-specific mentorship. “We try to nudge them out of their comfort zones, maybe try some things they might not initially be comfortable with.”

“We’re cultivating Catholic women leaders,” says Tesoro, “and people who are grounded in a good moral compass, to be able to affect change through stewardship. You can’t be a leader without followers and giving back, so it’s very much rooted and steeped in the core values of the school.”

Athletics

The school is small, though with a broad athletics program—there are 23 teams in a school of 225 students—so a vast majority of the girls are actively involved in something, and many take part on multiple teams. If a girl really wants to be involved, she will be; if a girl sort of wants to be involved, again, she will be. In a word, it’s busy. Because so many students are involved, there is by default a culture of activity and participation. As a result, even though physical activity isn’t regimented or mandatory for the most part, girls gravitate to athletics simply because it’s in the air. There’s also a level of recognition that accretes around individual athletes—“You’re not just the best girl in the school, you’re the best athlete in the school,” says Clayton Martino, a coach and instructor—as well as the competitive teams. “In flag football, last fall, we were good. We were really good. And that was the talk of the school—everyone knew what the flag football team was doing.” In larger schools or coed schools, no matter how good the girls’ flag football team may be, Martino acknowledges that they could easily be lost in the shuffle or be overshadowed by the boys’ teams. Here, they are celebrated—something that Martino credits with adding momentum to the programs and, ultimately, contributing significantly to their rate of success.

“If a girl comes here in Grade 9,” says Martino, “and, say, she’s a soccer player. She’s going to be on the soccer team, starting and playing on a competitive team, one that makes the playoffs.” At larger schools, the competitive teams are made up of Grade 12 students; here, it’s not uncommon for all grades to be represented. As such, girls have opportunities to participate at the highest levels, and to do so over the course of their time at the school.

While not all facilities are available on campus, there is nevertheless a wealth of resources nearby, and the athletics program makes use of all of them. The swim team trains literally just up the road on the campus of the University of Toronto Mississauga. The rowing team trains at the Don Rowing Club of Mississauga, a club that is approaching its 150th anniversary, having been founded in 1878. Through those kinds of partnerships, the girls are not only able to take part in athletics that wouldn’t be available to them otherwise, but they also enter dedicated athletic environments, something that itself can be transformative. While the school doesn’t have a century-old tradition of rowing, the girls nevertheless train within a setting that does.

The teams compete within the Ontario Federation of School Athletic Associations (OFSAA) and, as of 2017–18, began competing in the Conference of Independent Schools of Ontario Athletic Association (CISAA). While other schools may have a greater pool of athletes to choose from, Martino feels that allowing girls to help build the success of the teams, from when they enter in Grade 9, is a unique and valuable experience. Other schools might finish a season higher in the overall standings, but, says Martino, “playing time is more important, I think.” And he’s absolutely right. It is.

Pastoral care

“It’s a sisterhood,” says a parent. “And, I believe by accepting each other the way you are, and learning to give the best of yourself, that’s what we’re getting from this school. My daughter is a happier child. She feels that she is accepted here.” Community is an important aspect of school life, and administration works hard to ensure that students have a clear sense of their place within it. To that end, the school year begins with a retreat. Grades 7 through 12 participate in a four-day leadership program at YMCA Camp Wanakita in Haliburton, Ontario. Programming is centred around self-awareness, self-actualization, and community.

Academic guidance begins with entry into the school. Teacher advisors work weekly with girls in order to ensure that they are not only on top of their course work, but are also achieving some balance in their lives.

Susan Bates, a university placement counselor, comes in to work with girls around university application. A social worker visits regularly to lead workshops on healthy relationships, mental health, and stress management. “With high achievement comes high anxiety,” says Tesoro, “so we have accommodations for anxiety,” which can range from a pep talk before a math exam to more substantial interventions. A learning enrichment centre is tasked with helping girls manage stress, including as it relates to the ubiquity of social media, and test-taking skills.

The school’s administration is very open to trying new things, and that’s as true within the program of care as it is within the academic programs. “We once brought in therapy dogs,” says Tesoro with a chuckle, seemingly because she liked it as much as the girls did. “We’ve also created our own chapter of Jack,org, Canada’s only charity training and empowering young leaders to revolutionize mental health in every province and territory. Our goal is to help them to be resourceful, and to get the help that they need, when they need it.”

Workshops often include the parent population. Tesoro says, “it’s interesting when you do that, in the messages that the kids take and also empowering the parents to be vigilant on their end” to be aware of the changes that the kids are going through and how they can help. There’s also an annual speaker series run by the parent association, intended to both bring the parent community together and to support them in their role as parents of middle-school and high-school age girls.

The approach to everyday discipline is collaborative and restorative, rather than punitive. One parent reports: “two girls might be bickering, but the teacher talks not just to the two, but to the whole group, asking ‘What can we do to support them?’ …. It’s not just those two girls that have to deal with the issue, but rather the sense that we’re all responsible for each other. That’s huge.” While there are of course set guidelines, the school nevertheless embraces the belief that it takes a village to raise a girl, and it orients aspects of the school year in order to promote and facilitate that approach.

Food service

When asked about the challenges working within a girls’ school, the chef from Aramark Food Services responded, “Keeping open lines of communication.” Nice. “These girls know what they want. I relate it to when I directed food service at a golf course, where every client has their own needs,” which, frankly, was refreshing to hear. “You don’t want to have a customer/hospitality feel, you don’t want it to be cold. It’s good to keep it a healthy relationship, to get to know them.” He understands that he’s part of the front line in developing the girls’ relationship to food, and he takes that task seriously, offering a variety of healthy, quality options. The day we visited, the menu included roasted tomato bisque, eggplant parmesan, polenta and vegetables, built-to-order sandwiches, and the daily salad bar.

Getting in

The application process is standard for a school of this size and focus. The initial contact is with the admissions officer, Giselle Fernandes, once an online application has been submitted. Fernandes then guides families through the process. Interviews are most often conducted during a school visit, though, barring that, other arrangements can be made. As at most schools, the admissions process is one intended to ensure that the fit is right on both sides, and that the school offers the supports and opportunities necessary for student success. Academic records are important, though so too are the desires of the student, including her desire to become part of the Holy Name community. The school intends to grow the student body over the next decade or so, though it is keen to do it in a reasoned, careful manner so as to ensure a continuity of experience for the students currently enrolled. So, they’re in no hurry, something that parents should see as a good thing. And, even at that, the growth potential is fairly muted, with a desire to get to the right size, rather than a big size. The intention is to grow gradually. Most families participate in varying degrees within the Catholic faith. The discretion is on the side of the family, in the awareness that the values of the school, and the key events through the year, follow those of the founding orders.

A visit to the school while classes are in session is recommended. “We came all together for the open house, and we really liked the environment,” says a current parent of the school. “It’s really family oriented, very welcoming. It felt like home.” For some, that sense of belonging is a product of the school’s core values.

The day we visited, the Grade 5 and 6 students were performing scenes from Shakespeare, a culminating project within the English program. It was charming in every way. The delivery of lines was quick, to be sure, though that was a function of the fact that the girls had memorized them, long passages included, and really made them their own. The audience was comprised of parents, which was charming, too—it was the middle of a weekday, though an impressive number of moms and dads had made attending a priority. The performance wasn’t world-class, though, of course, it wasn’t meant to be. It was an instance in which the girls were challenged to stretch themselves, to accept the risks head on, to make a connection to the language and the themes of the plays, and to come away knowing that they had performed Shakespeare. Attending those kinds of events is as good an introduction to the life of the school as you can get. In our experience, you won’t need to go looking for parents to talk to—they’ll see that you are new to the school, and they’ll very readily talk to you. They are keen to tell their story; something that in itself is an indication of the health of the school.

Money matters

A running theme throughout the school is surprise at the range and quality of the offerings and programs, given the size of the school, and that extends to the financial aid program. The school awards more than $250,000 in scholarships and bursaries each year. All aid is needs-based, applicant-blind, and managed through a third party. The goal is to ensure that all mission-appropriate students are able to attend, as well as to ensure that all students are able to complete their high-school education within the school.

Tuition levels are in keeping with schools of this size and location, if perhaps a touch below the average. Tuition covers academic fees only; other fees, including transportation, uniforms, meals, or fees associated with extra-curricular activities, are incidental. Payment options include quarterly and monthly plans.

Parents and alumnae

In the past, parents often turned to Holy Name on the basis of the academic program in conjunction with the values promoted within it. Talking to current parents of the school, however, you’re most likely to hear about the strength and support of the community they’ve found there. Communication, by all counts, is open, frequent, and personal. Staff are credited with not only knowing each student’s name, but also where they are coming from, and where they would like to go. Teachers are available through email, and there are events throughout the year that provide opportunities for parents to interact, which they seem to do regularly and happily. One parent said of the parent community, “I feel like we have so much in common. We want our girls to grow together. We share our frustrations and all, but, bottom line, this is good.” Another added, “We all talk to each other, and we get along, and that’s very important.” The school actively promotes those kinds of parent relationships, and it is otherwise keen to have parents play a role in the life of the school, whether it’s major, minor, or in between.

Given the age of the school, the alumni community is relatively small and young. Even the earliest graduates are still either in university or just gaining a footing in professional life. Some do come back to the school, though, and the development of the alumni community will continue as it grows. Just as the school is keen to have parents involved in the life of the school, so too is their desire to maintain engagement with the alumni population.

The takeaway

HNMCS began in 1964 as Holy Name of Mary School, and it has grown and changed in the decades since. For a time the school was publicly funded, and while it operated continually through the years, it was re-established in 2008 with a new name—the current one—and as a fully independent school for girls. Today HNMCS is supported by the Basilian Fathers of St. Michael’s College School and the Felician Sisters, who co-founded the independent school. The vision of the school has also remained through the years, though was rededicated in 2008. Families who turn to HNMCS are looking for strong academics and values, and indeed they find both. The values that the school promotes those of the Catholic tradition, with an emphasis on empathy, justice, and excellence. The ideal student is one who shares those core values, will thrive within a challenging academic atmosphere, and is preparing for post-secondary education.

The program is defined by a young staff and faculty; new ideas; and an overt dedication to academic challenge, collaborative learning, cross-curricular instruction, and omnivorous curiosity. Because of the age of the school, there is a lot that’s new—such as the technology program, Innovation Time, the Elite Athlete Program, Engineering Career Night, and on it goes. “New” is a word that comes up a lot: this is a school that is developing, right now, in response to the needs of the students as they advance through the programs. Attention is given to areas of interest in which, historically, women have been underrepresented, including science, business, and engineering. Attention is also given to meeting girls where they are and growing with them from that point.

No school is for every student, and that’s true here as well. Holy Name comprises a community of girls who share a penchant for academics, are looking to continue their education at university, and who share a religious tradition and the values that are implicit within it. The ideal student is one who is grounded in the core values of the school, while also willing to grow into the school community and able to thrive in a challenging academic environment. Families are drawn by the academics in equal measure to the profile of the school community, including a very close-knit student and parent population.

Photography provided by Holy Name of Mary College School.