Quebec has the highest proportion of children attending private schools in North America. Seventeen percent of high school students attend private schools, a figure that is even higher in urban areas, such as Montreal, where 30% of high school students attend private school.

One reason is cultural, based in the traditions and the values of the population. Another is because the province provides subsidies to schools based on enrolment. That support is reflected in the quality of the schools found within the province. It has also encouraged the growth of a student population that is one of the most varied in North America and the world, drawing from a broad swath of the socio-economic, academic, and cultural spectra.

The official language of Quebec is French, and Quebec is also the only province in Canada that has just one official language. In other provinces, students can study in either of the country’s official languages—English and French—though authentic French-language instruction is limited and, for the most part, schools operate within an Anglophone cultural context to which French instruction is ancillary.

In Quebec, the opposite is true: most schools provide instruction in French, and English language instruction is limited and ancillary within the public education system. As such, the private schools in Quebec comprise some academic opportunities unique in North America, including that of living and studying in an authentic French cultural and linguistic context. Many families are drawn to schools within Quebec for precisely that reason.

1 | Language of instruction in Quebec |

Quebec has publicly funded French and English schools, schools in which either French or English is the principal language of instruction. The Charter of the French Language, also known as Bill 101, was adopted in 1977, and it remains the central piece of legislation regarding language within the province.

The purpose of the Charter is bigger than language—it is intended as one of various means of maintaining the rich and unique culture of the province, and to do so in a spirit of fairness and open-mindedness for all involved. The bill has raised controversy throughout its life, though the intention has never been punitive. Rather, the spirit of the bill is based in the recognition of the needs of the people of the province.

As such, the Charter speaks to many things. One of them is the place that language has within the public education system, including limits placed on students able to study within provincial schools where English is the primary language of instruction. An important proviso is this: the Charter addresses publicly funded elementary and secondary schools; it does not apply to Québec's colleges and universities or non-subsidized private institutions.

Bill 101 states that children who attend schools that receive public funding must be educated in French from Kindergarten through secondary school unless they apply and qualify for English language instruction. There are three paths that an application might take: to receive a certificate of eligibility, to gain special authorization, or to gain temporary authorization to enroll in an English school. There are a range of criteria for eligibility, and the Charter outlines those as well. Children eligible to study in English-language schools include:

2 | Who is eligible to attend English school in Quebec? |

Students who wish to study at an English-language public school or subsidized private school must apply to receive a certificate of eligibility. The result may be the provision of special or temporary authorization, though the process for all begins at the same place: an application for eligibility.

Again, it’s important to note that if a school doesn’t receive public funding, students are not required to gain a certificate of eligibility in order to enroll. Further, some schools receive subsidies for some programs, while not for others. Selwyn House School, for example, is subsidized at the secondary school level, so students in Grades 7 to 11 require the document on file. However, students in Kindergarten to Grade 6 do not need eligibility to attend the Elementary School at Selwyn House. Note also that some schools, such as West Island College, Emmanuel Christian School, and Villa Maria, offer both English and French language streams in settings that are otherwise dually immersive—in those cases, students who are ineligible for English instruction may nevertheless enroll in the French-language stream. For students in either stream, the experience is of authentic, robust dual immersion.

True, navigating eligibility can be tricky. That said, the school that you are applying to can let you know if you indeed require a certificate in order to enroll. The best case is to start with the school’s admissions officer.

Bill 115, passed by the Quebec legislature in 2010, introduced changes to the Charter (Bill 101). In particular, these changes allow instruction received in a private school to be taken into consideration when determining eligibility for instruction in English.

Under Bill 115 a student’s eligibility is determined using a points system, whereby an applicant accumulates or loses points based on a series of factors including the number of years they have attended English or French schools, and where their siblings went to school. A student must accumulate 15 points to receive a certificate of eligibility. Most students who have attended four years in English elementary school receive 15 points.

To receive a certificate of eligibility, a student is required to have at least one parent who is a Canadian citizen and meet one of the following criteria:

Special authorization for English instruction

Students may receive special authorization to study in English, if:

Temporary authorization for English instruction

There are several cases where temporary authorization for English language instruction can be gained. These instances include children:

Temporary authorizations for English instruction are typically given for a single instructional year, expiring on June 30 of that year. You can learn more about temporary authorization conditions by clicking here.

Whether you’re applying for a certificate of eligibility or a special or temporary authorization, the process is the same:

You will be informed directly of the decision in writing, typically within 10 working days. If the application was unsuccessful, you may lodge an appeal. If the appeal is based on a family or humanitarian consideration, the appeal must be made within 30 days of the initial decision.

3 | Cultural literacy |

Language, perhaps understandably, is an important issue when parents are choosing a school in Quebec, and certainly more so than in other areas of Canada. The Charter confirms that, though it’s also because the Quebec context provides families more options and opportunities for bilingualism, as well as more reasons to pursue them. In Montreal, for example, both English and French are spoken authentically, and students brush up against them every day in the course of their lives in school and beyond. The benefits of that experience can be profound.

“Language is like a door which enables you to learn the world,” says Mrs. Li, a parent in Montreal. “When you learn one language you get to know one part of the world. When you learn other languages, you will get an opportunity to know other parts of the world.”

Dr. Mary Maguire, professor emerita in McGill’s Department of Integrated Studies in Education, uses that quote to underscore the relationship between language and cultural literacy. She and others believe that learning a language can provide students with a more intensive, and ultimately more meaningful, engagement with cultural traditions, both their own and those of others. Further, learning a heritage language—one that is spoken by parents or grandparents—can provide a more authentic connection to ancestry and increased access to literature from that culture.

We typically think of bilingualism in fairly prosaic terms, such as job skills and international communication. But through her research Maguire has found that learning languages is often about much more than that; the languages we learn can impact our identity and our sense of cultural space. Maguire writes that “places are both physical territories with clearly defined borders and culturally constructed spaces through intricate social networks of social relationships.” Language, she suggests, can contribute to a sense belonging and identity within a cultural space, something that she feels is confirmed within the experience of Montreal’s multilingual population.

“Language is like a door which enables you to learn the world”

What Maguire goes on to suggest, is that within immigrant communities, language can create new identities that derive from an understanding of place that isn’t limited to one cultural community, but extend to the community of people who share a multiple cultural heritage. The term of art is “third space,” coined by Edward Soja. While he wrote primarily about geographical spaces, Maguire applied the concept to language acquisition and a sense of belonging within unique cultural spaces: “a new space between cultural collectives and individuals and historical periods.” She writes that “the expression of the self and the construction of the identity are both enabled and constrained by the appropriation of the linguistic and rhetorical conventions.” For example, children living in Montreal who are conversant in English, French, Chinese, or Armenian, will inhabit a larger and likely richer cultural space than, say, a resident of Montreal who is conversant in only one of those languages.

And, indeed, the diversity within the urban centres of Quebec can be particularly impressive. Montreal is often discussed as the closest you can get to Europe without leaving North America, and the lived experience of the city bears that out. Likewise, there are language programs that reflect that diversity, and students regularly come into contact with them. One example is the Montreal Hoshuko School, a Japanese language supplemental school which holds its classes at the Trafalgar School for Girls. Dual-language schools, augment the already significant attention to global education found in Quebec private schools. Alexander von Humboldt German International School, offer a trilingual intrusctional environment. At College Prep International, more than 25 languages are spoken within a student body of just 120 students.

The vast majority of Quebec private schools are dedicated to the promotion of true bilingualism, whether they operate principally in English, French, or both. Again, there are many that offer two streams of study, where others offer English curriculum courses, such as English language arts at Pensionnat du Saint-Nom-de-Marie. “There is really no strictly English school in Quebec,” says Brenda Montgomery of Selwyn House. “Even though we’re an English school, we teach some courses in French.” To varying levels, every English school in Quebec contains an element of French immersion. . Also unlike elsewhere in Canada, schools in Quebec, as Kells Academy, often offer French as a Second Language (FSL) programs as well as English (ESL).

4 | The Quebec Curriculum |

In Canada, the elementary and secondary curricula are set and overseen by the provinces, not the federal government. In Quebec the curricula are set by the Quebec Ministry of Education, Recreation and Sports.

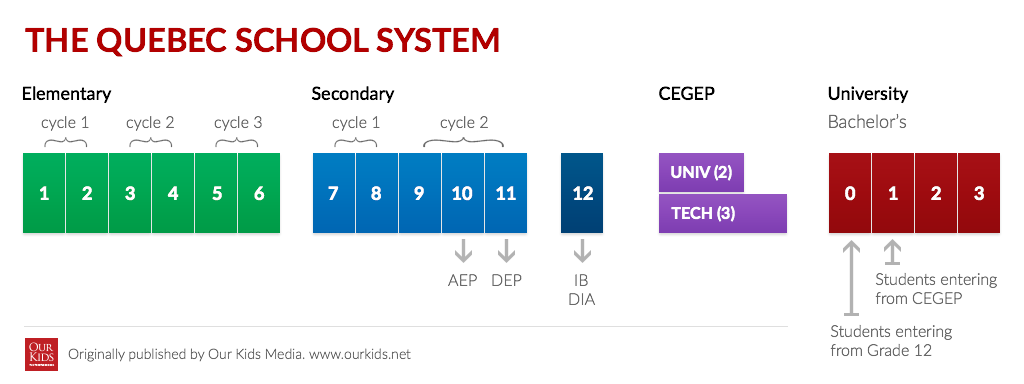

As in all the provincial curricula, the program of study is delivered principally by grade level, and that’s true in Quebec as well. Elementary school is comprised of grades 1 through 6, and secondary school is comprised of grades 7 through 11. Schools teaching to the provincial curriculum are also required to express progress by competencies and cycles, as outlined below.

Competencies are the educational targets specific to each subject. End of cycle outcomes are based in fluency with the core competencies of the subjects taught within the cycle.

Elementary school in Quebec has six grades divided into three cycles:

The cycles are intended to provide opportunities for instruction—allowing topics and concepts to be taught in an arc over the course of two years—as well as more meaningful assessment. The outcomes—termed competencies in the language of the curriculum document—are concrete abilities and understandings that students are asked to demonstrate. All the teaching within a cycle leads to those competencies. Students’ facility with the curricular outcomes are assessed throughout, though most significantly at the end of each cycle. For the student, the end of a cycle can signify a benchmark in their learning, offering a sense of completion and, with the start of a new cycle, a sense of progress and momentum.

The benefits of the cycles extend into course delivery and student experience, in particular in making more longer-term connections with instructors. “It allows us to have teacher teams that focus very much on a specific age group,” says Brenda Montgomery of Selwyn House. “You have the same teachers teaching the same students for two years in a row,” something which allows them to get to know the students better, and to better chart their social and academic growth. “there is a great deal of growth over two years in the life of a child.”

Secondary school in Quebec has five grades (formally given as roman numerals I-V) corresponding to grades 7 through 11. Upon completion of grade 11, students receive the provincial Secondary School Diploma (SSD).

Quebec is unique in Canada in that it is the only province that requires 11 (rather than 12) years of study in order to earn a high school graduation diploma. Students may apply for college entrance with that diploma. Students who intend to enroll at university must attend two years of college, known as CEGEP, and earn a Diploma of College Studies (DEC, Diplôme d'études collégiales) in addition to their high school diploma.

Due to all of that, the divisions that mark the progression through elementary and high school in other provinces—elementary, middle, high—aren’t reflected in Quebec. That said, some English schools will use those terms when talking about their programs, just as some will adopt those divisions within their student body. In those cases, however, it’s an expression of the culture of the school and student life within it, rather than the delivery of the curriculum. All schools, no matter the terminology, are required to follow the provincial curriculum as it is laid out, and to assess and report on student progress per the ministry template.

Quebec is also unique in that students are required to sit province-wide exams, set by the ministry of education, in order to receive their high school diploma. There are five in total, with students sitting science, history, and math exams at the end of their grade 10 year, and English and French exams at the end of grade 11. They have to pass all of the exams in order to receive their high school diploma. Should a student not receive a pass, they can rewrite the exams, all of which are offered three times each year.

All schools in Quebec are required to report student results in the same way, and using the same report-card template. The report cards can appear quite complicated, as indeed they are. competency and course grades are reported as percentages. Classroom assessments are reported numerically, based on a 1 to 5 scale, much like what is used in many European countries.

Report cards reflect the division of the curriculum into cycles, including two-year reporting periods for the majority of a student’s career. The only variance is in the last years of high school.

In Canada, “lycée” most typically references a relationship with the French ministry of education based in Paris, France. In the past, that relationship was of interest to French nationals, perhaps particularly, or to families expecting to move outside of Canada prior to the end of a student’s secondary career.

While that remains, today lycées attract a broader range of families, as at Lycée Claudel. The draw is a strong language program, one that is more robust than found in public schools. Families are also attracted by a curriculum that is delivered through a different lens, one that is more cognizant of the diversity of the global community and more reflective of a student’s place within that wider world.

Some schools offer baccalaureate diplomas in addition to the provincial diplomas. Of those schools offering international diploma program, some offer the International Baccalaureate program while others offer international diplomas from around the world. Alexander von Humboldt School, for example, offers the DIA, the German International Baccalaureate.

CEGEP, at its simplest, is the equivalent of grade 12. That said, there are some important differences, the foremost being that the program is typically more robust than the grade 12 programs offered elsewhere in the country. Some courses may be considered advanced placement courses, applied toward the completion of a post-secondary degree.

In a few cases—Centennial Academy is one—a CEGEP program is offered in addition to the secondary program. Typically, however, students attend a new school for their CEGEP year. They are free to choose between a public college, where there is no tuition required, or a private college, where tuition is required, though often is subsidized. The move places them within a context that is more like what they will experience when they move on to university. That, as well as the course load, can offer a taste of post-secondary education—and what will be required there—in ways that grade 12 programs typically don’t.

Students need to complete both the SSD and the DEC in order to apply to universities or colleges within Quebec. For those intending to apply elsewhere, such as Ontario, the CEGEP year is regarded as an equivalent of grade 12. University programs in Quebec have two entry points for undergraduates, either year 0 or year 1. For those applying to universities within the province, and who have completed two years of CEGEP, they will apply to enter the undergraduate program at year 1. For students arriving from out of province, and having completed grade 12, will enter the undergraduate program at year 0. So, between all of these variances, all students will graduate their undergraduate programs at the same age, and having completed the same number of instructional years.

There are also three schools in the province that offer grade 12 programs, one of which is Alexander von Humboldt School in Montreal. Students there can choose to continue through grade 12, earning the German International Baccalaureate diploma, and then apply to university just as out of province students do, entering at year 0.