Brentwood College School THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Brentwood College School, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Basics/Background

Conceptually at least, Brentwood is one of the older private institutions in western Canada, having been founded in 1923. The school has history, and, in some respects, it’s been a bit of a bumpy ride. Classes were first held in the Brentwood Hotel, overlooking the southern end of Saanich Inlet, and remained there until the school building was completed in 1925. All school activity with the exception of chapel was hosted in that one building, and the boarding houses, Cock’s and Round’s simply occupied separate floors. When it was destroyed by fire in 1947, only the chapel remained. With one term held in Copeman’s House at Shawnigan Lake School, the school then closed in 1948 and instruction ceased until 1961, the year it was reestablished at Mill Bay.

Brentwood was rebuilt through the instigation of alumni, and it was primarily a labour of love. While there was a healthy bit of nostalgia driving the recreation of the school, it’s interesting that it wasn’t associated with the buildings or even the location. Rather it was the feel and spirit of the school that they wanted to reestablish. D. D. MacKenzie had been at the original location. In 1973, as headmaster, he wrote that “the Brentwood of yesterday was small in size and limited in scope, yet it managed to inspire loyalties which have persisted through all the changes and chances of the school’s history.” In the dedication to the inaugural issue of The Brentonian, in 1964, the editor wrote that, “Just a little over three years ago, a group of men, all Old Boys of Brentwood College, met in Vancouver to put this school … into operation again. The new school had no money, no buildings, no staff, and no boys …” It was, in every tangible way, a new beginning.

“Be true to your ideals, guard your honour, set high our standards of excellence. Then, when your time comes to hand on the torch, you may justly feel proud in having played your part in the founding of Brentwood.”

—H.P. Hope, headmaster, in the Brentwood College Magazine, June 1924

So, while the school is approaching its centenary, given the fire, the move, and the ongoing development, Brentwood’s physical plan doesn’t reflect its age. If anything, it provides a fairly stark contrast to it. Only one building, Alexandra House, predates the relocation. It dates to the time of the Queen Alexandra Solarium, a hospital established through royal patronage for children suffering from polio and tuberculosis. A few buildings date to 1961, though the campus is overwhelmingly dominated by newer structures, most notably Crooks Hall, the Centre for Arts and Humanities, and the T. Gil Bunch Centre for Performing Arts, and the newly opened Foote Athletic Centre..

When Crooks Hall was completed in 2010 it became the centerpiece of the campus complex both by its physical prominence—it announces itself quite aggressively—and its design. Brentwood is very conspicuously not a school of brick buildings draped in ivy. The materials—softwood, large windows, high ceilings, overt references to post and beam construction—imply the natural history and cultural heritage of the region.

As a green building, Crooks Hall was intended to restate the values of the school. It includes a living roof, a grey water recycling plant, and heating and cooling systems that use night air and geothermal exchange. The Centre for Art and Humanities, completed in 2012, continues a commitment to place, aesthetics, and sustainability. The new Foote Athletic Centre is an athletic jewel of some 65, 000 sq ft and continues to reflect the west coast aesthetic of its predecessors.

The Eldon and Anne Foote Athletic Centre

The Eldon and Anne Foote Athletic Centre is a product of the 2013-23 Strategic Plan, Setting the Standard. The centre addresses a growing student population, as well as growing diversity within the athletic program. The design continues the West Coast theme of the campus, sitting sympathetically with the existing infrastructure and natural environment. It was dedicated on September 22, 2018.

The Eldon and Anne Foote Athletic Centre is a product of the 2013-23 Strategic Plan, Setting the Standard. The centre addresses a growing student population, as well as growing diversity within the athletic program. The design continues the West Coast theme of the campus, sitting sympathetically with the existing infrastructure and natural environment. It was dedicated on September 22, 2018.

Key words for Brentwood College School: Teamwork. Community. Place.

Atmosphere

Throughout, the development of the school has been guided by a desire to impart a sense of place, a commitment to experiential learning, and a view to providing students with the tools they will need in their academic, professional, and personal lives. There are some long-standing boarding school traditions that Brentwood lays claim to, but the administration also intends to grow the school in ways that are entirely unique and innovative. And, certainly, there are many things—such as the tripartite program, a dedication to cross-curricular instruction—that are clear examples of that impulse.

Still, the place itself is the first thing that commands a person’s attention. “For families that visit,” says Clayton Johnston, director of admissions, “a trained monkey could sell the school.” Frankly, there’s some truth in that. “Once they get on campus and they see the kids, and they see the engagement, it’s pretty much game over.”

The buildings, including a significant use of outdoor instructional space, describe a porous interface between indoor and outdoor environments. The decision to celebrate the outdoor environment, and to make the most of it, stems from a core belief in the impact that environment can have on the educational experience. Bud Patel, head of school, says that “research indicates that setting and environment does have a massive impact on learning,” something that he and the leaders of the school before him have been dedicated to making the most of.

The bay provides a focal point, as rightly it should. A humpback whale took up residence in the bay for three weeks last year, and seals regularly sun themselves on the rowing docks. While most schools are situated around a quad, with buildings describing an outside boundary and facing in, Brentwood is built along a shore, with the buildings facing out the bay and beyond. Sitting in the dining hall, students look out at the snow-capped peak of Mt. Baker, in Washington State, in the distance. The metaphor all of that suggests—looking out rather than in—is embraced.

It’s hard to imagine a setting better able to inspire people to think, work, and grow together. And, by all accounts, that’s exactly what it does. “The students genuinely care for each other,” says Cheryl Murtland, “and they care about the school. So I think that’s becoming more of a trend in independent schools now than it used to be—where it was kind of an ‘us and them.’ [Now] they feel they have some power in how the school is going to go.”

Sixty percent of the faculty live full-time on campus, contributing to the village feel. “The day students want to be here all the time,” says Murtland, and all have the option of doing precisely that. “They stay overnight here on Saturday nights because they don’t want to miss out on what’s going on.” For boarders and day students alike, Brentwood is very much a seven-day-a-week kind of place. “The boarding culture prevails in all that we do,” says Johnston. “It is the hub of what we do. And if you’re looking for a boarding school, I think that’s of primary importance.”

The nearest centres are Victoria to the south and Duncan to the north, and the school is set apart from both, something that recommended the property when the school was being re-established. “There’s a huge advantage,” says Johnston, “because you’re not in the middle of a city, and you build your own community.” Boarding students live on campus in eight houses, overseen by house parents that live in the houses as well. Dorm amenities include a fitness centre, game rooms, and lounges, and laundry service is handled on site.

The academic environment

Harbinder Grewal enrolled her son, Kavi, in Grade 9, and he will graduate this year. The primary attraction was the strength of the academic program, one for which the various metrics of success were in evidence: scores, university admissions, etc.

While she didn’t perhaps think of it then, Grewal feels that the academic environment—one in which social capital was gained in part through academic achievement—was equally responsible for Kavi’s success. “It’s nice to get the great marks,” she says, “but if you’re kind of alone, and you feel alone … [and seen as] just a geek in the library.” At Brentwood, he isn’t. “They respect him there. He feels respected. He feels like his hard work is valued. He just walks taller. … I don’t know if he would have been that way had he not had this experience.”

Glynnis Tidball’s two daughters have both attended Brentwood, despite the fact that private school, let alone boarding school, wasn’t something she had ever imagined as a part of their family life. The academics were important though, again, it was the context that the school offered that ultimately tipped the balance. “I don’t think that I ever would have imagined a place like Brentwood existed,” says Glynnis. “Until [Gwyneth and her father] went over for the tour, Gwyneth’s dad was a hard sell on private schools. After he came back from the tour he said, ‘wow, that’s a fantastic school.’” Her daughters found a school where “it was cool to be smart, cool to be interested,” this in contrast to their experience prior. Lisa Krasny has had two children attend Brentwood, and for them as well, the atmosphere was an important draw, “the way that kids participate, everyone on the same page and wanting to do well.”

Mill Bay can seem a bit sleepy, and it is. The town and the school exist in remarkable sympathy with one another, with members of the local communities coming onto campus for performances and events—the regatta, the annual Concert for a Winter’s Night, the TedX conferences, visiting lecturers—and students going off campus to volunteer in local schools and the health center, and take part in local environmental initiatives.

Shawnigan Lake and Brookes Shawnigan Lake schools are nearby, and they contribute to the community that Brentwood participates in. Also nearby is an international marine research facility, the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre, a campus shared between the biology faculties of five universities. It houses 3000 square metres of state-of-the-art laboratory space, and Brentwood students regularly attend to make use of it, often working in partnership with university faculty and students. Strathcona Park Lodge is a leadership centre “up island” as they say, and the school makes good use of that facility as well.

In all of that, Brentwood benefits from its seclusion as well as its place within a larger, and deceptively diverse, academic community.

Student population

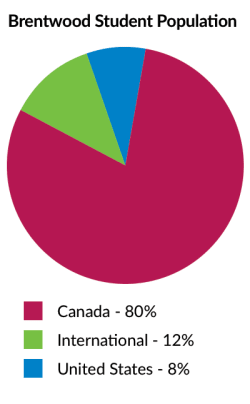

The student population sits at about 559 students, with more than 80 percent boarding on site. Girls were first admitted in 1972. Gender parity was reached in the 1990s, and it remains today. In any given year, 80 percent of the students are Canadian and 8 percent are from the US. The remaining students arrive from more than 40 countries around the world.

“We’re at an advantage at a school like this,” says Murtland, “where we have students coming from so many different countries. … we don’t have to fabricate those situations where we’re asking someone to think in a more global way.” The perspectives represented in the classroom are divergent and authentic. “I have a student from Ukraine in my class and he has very strong opinions about Ukraine, which shocked a few students, because they don’t’ really know that much about it. … you don’t necessarily think about being so passionate about your country in that way. You can be a proud Canadian. But what does it mean when the tanks are coming into a part of your country and another country is taking it from you? And what does that mean at 17 years old?”

Global awareness is, after all, as much an awareness of ourselves as it is an awareness of others. It’s about understanding that we all share a world, and that we all bring our skills, perspectives, and prejudices to it. International recruitment is closely managed to ensure that the feel remains Canadian in terms of values, diversity, and language. Canadian social norms and perspectives are actively promoted, and using that terminology.

Academics

An academic review completed in 2015 provided a means of taking stock and formalizing the goals and the values that had been simmering at Brentwood for decades. The core commitment is to developing literacy, numeracy, and life skills necessary for success in post-secondary education. That said, those aren’t posited as goals in and of themselves. Rather, they are situated within a stated and overarching dedication to some higher-order concepts: curiosity, investigation, student-centred learning, experiential education, global mindedness, and inspirational teaching.

The review process toward creating the academic plan, says Murtland, served to highlight some fairly stark opportunities for the school, including one to take better advantage of the marine environment across the curricular areas. There, and elsewhere, she sees the plan as a truly living, breathing document, one that underscores an ongoing need to dig a bit deeper, now, into curricular development. “If we say we have [for example] a commitment to experiential learning, then that means everybody is looking for opportunities to have authentic learning experiences for our students, whether it’s off campus or on campus.”

The plan is confirmation of the various academic values of the school, though, she says, it has also made room to really dig a bit deeper, and to start conversations around extending those values in creative and productive ways. That includes a dedication to not siloing the various aspects of the curriculum, and otherwise ensuring that the student body doesn’t divide itself into various cliques of interest—where the rowers, say, are distinct from the drama kids and never the twain shall meet. The school takes great effort to highlight where physics, say, meets athletics, or where the arts meet entrepreneurship.

“I’d never seen teachers like this. This was different. They were so inspired and exuberant about the teaching, what he was learning, and how he was doing.”

—Harbinder Grewal, parent

“The arts are the pathways to creative problem solving and collaborative learning,” says Edna Widenmaier, the school’s director of arts, “so I encourage the integration of arts into the academic program,” something that can take a range of forms. She recently worked with Grade 9s studying migration, having them research the wagon trains with the goal of role playing various aspects of that experience. Yes, the result may not be entirely accurate, but Widenmaier feels that the benefits obtain in a greater comprehension of the challenges that settlers faced. It’s one thing to know that there weren’t supermarkets back then, though quite another to make that question personal, where a student is faced with the dilemma of how they will feed themselves and their families.

“Have you done the little more than was required, rather than the little less?”

—Headmaster, Mr. A. C. Privett 1946

Widenmaier has made it her work to ensure that those types of cross-curricular connections are made tangible in the students’ daily experience, as do the directors of the other academic areas. When I toured, students were in the new Maker Space 3D-printing a model of the human brain, a particularly stark example of the intersection of technology skills, coding, and human biology. (And patience. It took hours to print.) Some connections may be somewhat superficial, though others aren’t, and the school’s attention to creating opportunities for significant overlap of interest is admirable.

Harbinder Grewal notes that finding a place in the arts was difficult for her son as well. “He draws stick people.” Thankfully, she admits, he had options, prime among them being debate, which he ultimately took part in competitively. “Both of my children are naturally more focussed on learning than marks,” says parent Glynnis Tidball, “and I think for them the tripartite program has been fulfilling. All individuals benefit from being well rounded in the arts, physical activity, as well as academics. Our family has never been one to push the kids to get good marks. What was important is that they learned, and put their best effort into learning. And I think that is important at Brentwood, too.”

Experiential learning

“I’m a geography teacher,” says Cheryl Murtland, “and if you’d asked me at the beginning of my career [about experiential learning] I’d have said ‘well, we go on field trips.’” She chuckles, knowing that our understanding of experiential, hands-on learning has advanced a bit in recent years, and this precisely because of the kind of work that’s being done at schools like Brentwood.

For Murtland the goal is to create authentic learning experiences, both in class and out. “It’s all experiences … some of them are planned, but others are just taking advantage of the local environment.” For example, there is a fish ladder at the edge of the property, and when the salmon are running, Grade 10 science students assist the volunteers who are grabbing them and putting them in trucks to be taken up stream. Likewise, there is a dedication to finding mentorship roles for students within the larger community, which at times is as simple as becoming reading buddies to kindergarten students within the local schools.

She’s quick to note that it’s more about simply having experiences, but providing opportunities to affect outcomes. The business program, for example, gives students a chance to start a business, run it—for example, they have opportunities to present their business concepts during the annual regatta—and to see their concept succeed or fail. Either way, there’s a lot to learn. “The most impactful part of experiential learning is the reflection on the experience … How it lets them see something differently, or consider something differently.”

Instructional authenticity

When touring the campus, you’d be forgiven wondering if the programs risk becoming a bit too grand, or dedicated to achieving professional standards for the sake of those standards alone. The theatre program, for example, is significantly more robust that you’d expect to find at a secondary school, including a professional performance space complete with professional lighting, seating, and stage materials. There is a costume designer on staff, full time. She is tasked with creating the costumes for the productions and which are afterward rented to other schools and professional theatre companies on Vancouver Island. The school also employs a professional choreographer and professional lighting and sound designers.

That dedication to creating authentic experience is emblematic of the approach across curricular and extracurricular programs. Nothing is undertaken halfway. It’s impressive, but, again, it’s easy to wonder if there isn’t a point of diminishing returns, if all those bells and whistles are necessary or even helpful to students. Widenmaier insists that they are. “It’s important because it raises the bar for the students. And it creates the sense of excellence, that we expect excellence. … It affords, for students who want a really enriched experience, to have it. … We don’t do high school productions.”

That raising of the bar isn’t unique to theatre, but rather is symbolic of an approach adopted across the school. “This team of people is really encouraging students to fly high. It transforms the learning experience that they have, when you have these amazing facilities. … We don’t accept the ordinary here.”

“You can’t be the ‘sage on the stage’ anymore … That’s the old British school system, and it doesn’t work with kids anymore.”

—Edna Widenmaier, Director of Arts

Certainly, they don’t, though that can be somewhat trickier than Widenmaier makes it sound. Ultimately it’s a balancing act. Some students, let’s face it, are ordinary, and exceptional environments could just as easily alienate them as inspire them. Support is important, and raising the bar is only useful in an atmosphere where all feel included in the larger project. To be fair, the school does truly demonstrate its dedication to ensuring that every student finds his or her niche and has a clear understanding of what success means specifically for them. Still, students with special needs could very easily be lost in the shuffle here. It’s intense. Rightly, the school is very attentive to the admissions process, ensuring that students arrive with the tools, the desire, and the dedication to make the most of what Brentwood has to offer. A rich and developing program of pastoral care intends to address any academic or social stressors that arise in a student’s life while at school.

“You will no doubt label me as old-fashioned and square when I speak of those things that I hope that you remember and that will give you a greater chance for happiness and satisfaction in life. Truth and honesty still pay big dividends; there is a joy to be experienced from reward for hard work; tolerance, thoughtfulness, and respect for the other fellow bring satisfaction; there is a difference between good and evil, right and wrong, between honesty and dishonesty. And the difference is important.”

—D. D. MacKenzie, headmaster, addressing the student body, 1973

The instructional day

The average day at Brentwood is busy and challenging. “If you look at their daily schedule, they’re going flat out, says Blake Gage, director of athletics. “It’s non-stop from the time they get up at 7 right through until they go to bed at 10 or 11. Across the board, what I hear from students after their first 8 weeks is ‘I had no idea it was this busy.’ … I would challenge any adult to live a day in the life of these kids”.

Busy in a boarding setting is a very good thing, so long as the schedule doesn’t become onerous, and administrators and instructors are keen to ensure that the right balance is kept between work and leisure. “It’s very busy,” says parent Lisa Krasny, “but they’re all in the same boat. So, it’s not a problem, because everybody is doing the same things. And, you know, I can see the benefit of being busy at a boarding school.”

The instructional day, proper, begins at 8:15 and ends at 1:15, time devoted to pure academics. At lunch time students change out of their uniforms, and spend the afternoon with extracurriculars. Three afternoons each week are devoted to fine arts and performance activities, and students are free to choose from a menu of 37 arts options. Another three afternoons each week are devoted to athletics, with 24 options for students to choose from.

That’s a lot, though not necessarily more than you’d expect to find at similar schools of this size. The difference is access. Through the scheduling—academics in the morning, arts and sports in the afternoons—students are able to take part in more options than they might within a more typical, 5-day instructional week. For example, they aren’t required to choose rowing at the expense of pottery. Instead, the schedule not only allows them to do both, but requires them to; athletes can’t avoid participating in the arts, and artists can’t avoid regular physical activity.

It’s quite cunning, actually, and it’s easy to wonder why more schools don’t adopt a similar model. That said, it’s not entirely a movable feast. To have a similar schedule requires the right context: a student population that is focused on boarding, a day student population with full week access to the campus, and a strong on-campus community that remains vibrant seven days a week. All of which is true of Brentwood.

“One thing I would say,” says Grade 11 student Mark Wheaton, “is that we’re worked pretty hard, for a high school. We’re on six days a week, and even on Sunday there’s homework.” In the evenings duty staff oversee homework from 7:30 to 9:30. Students have to hand in their phones at the beginning of that time, and get them back at the end.

“You do get tired sometimes.” Wheaton notes that, nevertheless, there is time to relax. “There’s a break just about every month, so I get to see my parents lots. The break is normally about a week. For example, mid-term is about a week and a half, and I have week off there. There are three weeks at Christmas.” So, while the days and weeks might be quite full, there are frequent opportunities to sit back a bit and have a breather.

Grade 8 Day Program

The Grade 8 program, in its current iteration, is a recent addition, first offered in 2014. The program was created in response to changes within the local public school system, which had removed middle school, per se, by folding Grade 7 into the elementary years and grade 8 into the high school years.

As such, Grade 8 at Brentwood operates independently of the core 9 to 12 program. It operates around a 5-day instructional week, with classes in session from 8 to 3:30. The program is relatively quite small, with only 20 students enrolled each year.

The ideal student, as you might imagine, is one intending to stay on at Brentwood for their high school career. The one caveat—and it’s a big one—is that participation in the Grade 8 program doesn’t imply admission to Grade 9. It truly is a year and a program unto itself, and students intending to stay are required to apply for enrollment into Grade 9, just as any other student would. Likewise, Grade 9 remains, conceptually and academically, the foundational year of the Brentwood program.

Rowing at Brentwood

Rick Mercer commented in 2011 that “If this high school was a country, in terms of overall medal count, they would have placed 54th out of 200 nations competing at the Beijing Olympics.” Unlike the countries at the Olympics, all of those medals were won in a single event: rowing.

The history of rowing at Brentwood, given that level of success, isn’t what most might suspect. There was a successful rowing program from 1923 to 1947, though of course it languished in the hiatus. Tony Carr says that when he resumed the program in 1964 “what we had were just a bunch of dilapidated old shells, and I spent a lot of time … back at the dock fixing something.” Rowers were continually returning to shore for on-the-fly repairs. “I’d be kneeling down in front of these old boats,” says Carr, “putting bailing twine, wire, or whatever would hold the thing together for the practice.”

“With only three members of our First Eight returning to the school, the prospects for a good season were rather slim … “

—The Brentonian, 1969

When John Queen arrived at Brentwood in 1974, he hadn’t sat in a boat. Nevertheless, that wasn’t seen as an impediment to him becoming a coach for the rowing team. “For me it was an entirely new field.” He was hired as a physics instructor. “The whole thing was strange to me, except that rowing is based almost entirely on physics. The power of the lever. So, from that point of view, all I had to do was apply the principles which I taught in the classroom and, there we go. It was easy.” He chuckles at the thought, knowing that it wasn’t quite as easy as he now makes it out to be.

Queen nevertheless became a storied coach for the school, and his imprint on the program was indelible. His first priority was teamwork, impressing rowers with the need to work together toward a common goal. His second was the need for new equipment. At his insistence the school upgraded the stock, bringing it to a point where the program could be taken seriously. “A couple years later,” says Carr, Queen “had very, very good quality crews and the confidence to take them to championships.”

That competitive aspect of the program wasn’t so much at the instigation of the coaches as it was a student, Joel Cotter. He decided to take part in the 1969 Canada Games in Halifax, and the school chose to support him. When talking about it now, the decision seems to have been made somewhat off the cuff, and perhaps it was. Nevertheless, Carr sees it as an essential turning point for rowing at Brentwood. It was the first time that they thought of the program in the light of national competition. Carr says that Kotter “caused us to open up our eyes.”

Still, it wasn’t pretty. “We spent the whole summer getting over there,” says Carr. Two rowers and two staff climbed into a station wagon—a tent trailer, and all the equipment, coming along behind—for the long drive across the country. Not surprisingly, perhaps, they didn’t place in that Canada games, but it was a start. Within a couple of years they were winning at the BC games.

In 1972 they attended the Henley in St. Catharines, Ontario, with the intention of beating Ridley. To say the least, it was an audacious goal. Ridley was widely considered unbeatable. In the months and weeks leading up to the event the Brentwood team members put up charts outlining the hours of training ahead, and began working methodically toward their goal. Says Carr, “I remember, at that point, saying, ‘they will succeed.’” He perhaps didn’t say it out loud, but he was right. They did. Despite the fact that no one knew them, or that the program was founded just 8 years prior, they took home the Canadian championship. “Success at last,” read an editorial in the 1972 edition of The Brentonian, the school yearbook. It continued, cheekily, that “The long drought is over”—this despite the youth of the program—”and the Brentwood first crew finally showed its true potential in winning the coveted Canadian schools championship in a record time of 4 minutes 25.6 seconds for the 1500m course.”

Attracting the attention of the world

For years Brentwood retained an underdog persona. “We went there very, very humble,” says Jennifer Browett, a member of the first women’s team to race at St. Catharines for Brentwood. “I’ve been to world championships, I’ve been to Olympics, but I still remember this race clear as day.” She’s able to recall very specific details of the race, such as the fact that the fourth stroke in faltered a bit. “I felt so incredible. Like I was a part of something so much bigger than just a crew.” They won gold.

The Brentwood Regatta began in the early 1970s, and initially was a competition of two, though was international from the get go. Lakeside School came up from Seattle, they rowed, had lunch, and went back home again. It remained that way for a number of years, adding a few competitors—Shawnigan Lake was the next to attend—but remained strikingly DIY. Which niggled coach John Queen. He felt that a world-class school deserved to host a world-class event. So, he did what anyone might do if they wanted to start a world class event: he printed a flyer. He then sent it to rowing clubs around the world, and waited patiently for the world to arrive.

“He set his sights incredibly high,” says Carr. “Me being the doubting Thomas, [I] thought ‘this will never happen.’” But it did. The event attracted crews from across the US, Mexico, Britain, and even Australia. Less than a decade prior the program had no crews, no equipment, and a coach who had never sat in a boat. Still, by the end of that decade, Brentwood had become the team to beat and was host of a highly regarded international regatta.

So much of the story is improbable, yet there it is. To date, the program has produced 22 Olympians, and as a club competes at the highest level of the sport. They don’t drive station wagons to the events anymore, but the spirit, in some important ways, remains the same as it ever was. Says Carr, “I would hope that rowing is not just about athletics and about winning. Rowing is about life lessons and creating a platform from which to have a meaningful and productive life.”

What rowing means

Something that isn’t readily apparent about the rowing program is that, since the very beginning, the attraction has been less to the competitive aspect, or establishing a Brentwood brand, than to the analogue it provides within the life of the school. John Queen appreciated rowing as disciplined and reasoned—applied physics—that provided a tangible example of the value of consistency, precision, and dedication.

That approach to rowing—less as an end in itself, more as a means of expressing some of the core values of the school—continues despite the medals, the banners, and the accolades. Rowing is seen as an activity that promotes active living, constructive competition, and teamwork. Likewise, it’s seen as a pure sport, given that it’s not something that students involve themselves in with an eye to achieving a profession. There are no professional rowing leagues. It is what it is, and rowers are aware that it’s only one aspect of their lives, not the entirety of their lives. The Olympics might be wonderful, but students are always aware that there is life beyond, and that they need to be prepared for it. Indeed, the list of Olympians might be impressive, though the success that those rowers have had since is equally impressive. In a sense, the school administrators do themselves a disservice when listing its Olympians by not indicating, in the same listing, the fields that they have gone on to find success within. Some are involved in athletics, but most aren’t. That, too, is an important part of the Brentwood story.

“Rowing teaches discipline, humility, teamwork … all the good things.”

—John Queen

Pastoral care

“We never considered boarding,” says Christien Kaaij, “it wasn’t something that was ever in our experience.” That said, she now has two children currently enrolled at Brentwood. Her son Casper became interested in the school through intramural basketball. That, coupled with his need for a challenge, was the impetus to look more closely at Brentwood.

Even then, she worried. As you do. “I always hated the idea that the kids would be completely gone, that they would really leave the house and I wouldn’t be very involved.” She’s happy to say that they check in regularly. “I must say the school is really supportive of that. They will knock on his door and tell him, ‘don’t forget, this is the time to call your parents.”

The school’s program of pastoral care begins there, in the houses, and extends to a robust program of peer tutoring and academic counselling. Formal university counselling begins at the end of Grade 10 and prior to Grade 11 course selection.

Every student is assigned a faculty advisor that they meet with each week. “It’s about checking in, seeing how things are going,” says student Erin Berry-Dillen. “Maybe a teacher is giving too much homework, or stressing out a class, which will always happen from time-to-time.” She says that, because for all the students in the advisory group—typically it’s ten or so, all in the same grade—it’s an opportunity to reflect on the classes that they all are currently taking. Sometimes the result is a shared resolve to approach whatever challenges a class may present. At others, it’s an opportunity for faculty to reflect on the kind of instruction being given, or how it might conflict with other aspects of student life.

“Advisors call to talk to us about effort ratings and that kind of thing.” says parent Lisa Krasny. “They have a really good parent portal site that they upload things on. They really do know your children there.”

In all, there is a good range of pathways to support. Advisors provide a point of contact for parents. The health centre offers medical clinics twice a week, and includes examination rooms, isolation rooms, and round the clock nursing care. All ongoing care, including orthodontics, ophthalmology, and counselling are managed by the staff of the health centre. The staff includes a physician, nurses, and two counsellors.

“I find them very responsive,” says Kaaij, “but also, proactively, if they see something they will reach out to you. You will get an email from the medical clinic saying, you know, ‘this is what we’ve seen’ that kind of thing.” Kaaij says that she’s regularly in touch with medical staff, administration, and her children’s academic advisors.

When asked about access to care, student Mark Wheaton says, without taking a beat, that “mental health awareness is huge at this school. The health centre is a great resource, and there are counselors there. Intervention is triggered by peers and faculty, if not the students themselves. “What I’ve heard is if a friend or a houseparent notices a person is struggling, they help them seek counselling.” Students are very clearly aware of the support available, and are made cognizant of the various pathways to care and their place within them.

“I know that occasionally, for all teens, there are difficult times,” says parent Glynnis Tidball. “Whenever they’re having a difficult time they talk to their house parents, who have a good sense of what’s going on, and they check in with students regularly. And you sense it whenever you go over there. When you walk through the house or around the campus, you get a sense that the kids are comfortable and happy … and if I ever thought they were entering an environment where they aren’t emotionally supported, in every way, I never would have sent them.”

Addressing diversity

“We’re not from a rich family, so we can’t afford many of the things the others kids are able to do,” says Kaaji, “but that never is an issue. You never hear about excess. It’s really about brotherhood and being equal in how you treat each other. In a community sense it’s nice to see them all hanging together.”

“When we dropped him off the first day they had this parenting meeting in the boys’ house. One of the kids, he was in a leadership position in the house. And, he is clearly a kid that in many schools would have been bullied. It was so nice to see that he was loved by all his brothers in his house, and was appreciated, and that he was also made the leader of the house. I really do feel that all kids are welcome there. It doesn’t mean that you have to like everybody—and of course you don’t have to like everybody. But there is a real feeling of brotherhood, you know, looking out for each other and respecting each other.”

The houses that students live in are very much the front line, so to speak. “Being away from home can definitely be tough for some people,” says Wheaton, whose brother was an example. “He was very homesick, and found it tough being away from our parents. He found that the more he was in the house,” and the more he integrated with the community of his house, “the more he liked it.” He says that “as soon as [new students] get to know the guys in the house, and that the teachers here are very caring and are there to help you,” many of the initial anxieties tend to melt away.

Academic counselling begins in Grade 9. Students are assigned an academic counsellor as well as 10 other students that they’ll meet with throughout their career at the school. Groups meet regularly to discuss any issues that they share, and have opportunities to meet individually with advisors as well.

Admissions

“I only have two criteria to accept students,” says Clayton Johnston, director of admissions. “It has to be the student’s choice to be here, and they have to have the ability to handle a university prep program. So, it’s about desire and potential.”

Brentwood doesn’t typically have open houses, per se, in the way that many private schools do. This is in part because the majority of students board, and also arrive from fairly far afield. Recruitment and information events are held throughout Canada and around the world each year. That said, all families are welcome to visit the campus for a tour, or to attend any of the events throughout the school calendar. The annual regatta, the TEDx conferences, school plays, as well as community events held on site are all opportunities to get a sense of the campus. Tours are arranged through Clayton Johnston, director of admissions.

The admission process includes all of the things that private schools typically require, including completing a detailed application, providing references, and an interview. Completion of a general aptitude test may be required as well. Brentwood has a rolling admissions policy, and applications are accepted throughout the year based on availability.

Often prospective students attend a day of classes and spend a night on campus. Lisa Krasny’s son Carter visited, at least initially, under the advice of his older sister, who was a student. “We really didn’t think he would go,” says Krasny, “And then, after a day there, a sleepover, he came back and said ‘I’m going.’”

Money matters

Almost 30% of the students receive some type of financial assistance, and the school has a robust program of student awards and scholarships. Awards are available to students enrolling as boarders, who are permanent residents of Canada, and who demonstrate high academic ability. Both needs-based aid and merit scholarships are available. Brentwood participates in the Financial Assistance for Canadian Students (FACS) program, operated by Apple Financial Services. While this is designed for Canadian families, all families seeking financial assistance can apply using FACS.

Alumni

As you might presume, any list of notable Brentwood alumni is going to be dominated by rowers. As much as that reflects well, it doesn’t serve to illustrate the diversity of the student population, something which is equally a credit to the school. Graduates, for example, include Rachel Evans Schiller, founder and CEO of KOOSHOO, an online eco-fashion and accessories brand run out of offices in BC and California. At the other end of the spectrum, in some senses, Jamie Johnston runs Mobile PD, a Texas-based tech company creating law enforcement mobile applications. Johnston credits Brentwood with “developing strong work habits, ... the emphasis on creating a balanced life” that set the foundation for his success. Hamish Purdy is a renowned set decorator, having worked on a long list of films including Mission Impossible, Man of Steel, and The Revenant. Michelle MacLaren, director of Game of Thrones and Breaking Bad was in the class of 1982. Wade Davis, ethnobotanist and author of The Wayfinders and Into the Silence, studied here, too.

They, and others (and, yes, the rowers, too) are very tangible examples of some of the key values—entrepreneurship, environmental sustainability—that are the intentional cornerstones of the Brentwood program.

Alumni programs

The annual regatta attracts past students and athletes, and doubles as a homecoming event. An annual reunion occurs each summer, and the school, via the Old Brentonian Executive, also provides support in organizing alumni events across Canada and around the world. “Brentwood has become more important to me as the years have passed,” writes Bruce Foreman. Often the school provides a touchstone for graduates as they continue on in their lives.

“Visually speaking the school has changed,” wrote Marisol Van Vliet after attending a reunion last summer. “Yet Brentwood itself has not. Brentwood, for most of us alumni, was more than a campus, more than a temporary home. It was an experience we Brentonians all have in common, and as such, a sort of bond we share. And while our experiences may have differed over the years and generations, in the end it was an experience we all went through in our own right.” While she many not be explicitly aware of it, Van Vliet’s thoughts mirror those of the intentions of the board when recreating the school in 1961.

The takeaway

All schools pride themselves on being unique, and to varying degrees, all of them are. Brentwood, though, perhaps stands out more than most, and not only because of the intentions that have underwritten the development of the school over its life. There is a nice balance of isolation—being up island and at a remove from Victoria—while close enough to not feel overly remote. While it’s perhaps not initially apparent, Brentwood is part of a much larger academic community, something it quite rightly makes the most of.

The students come to campus because they want to, per the admissions standards, and they stay on campus because, geographically, it’s a community unto itself. The admissions program is robust, and the school reaps the benefits. The student population is engineered to be diverse, yet not prone to siloing based on language or national identity. Academics are strong, and of course that’s something that they share with a majority of private schools that are Brentwoods peers. What differs, here, is how they are presented, with an imperative for students to take part in all aspects of curricular life, and to discover commonalities between them. Some students grumble—not all athletes welcome time in the pottery studio—yet the imperative of the tripartite program and the boarding culture remain, something that parents, perhaps quietly, appreciate. If there is a better means of creating well-rounded graduates—something that all schools intend—it’s hard to imagine what it would be.

No, Brentwood isn’t for everyone, but it’s also not just for rowers or the academically or socially elite either. The program of care many not have all of the branding that it does at other schools, but nevertheless its presence is pervasive throughout student life, ensuring that all get the academic and emotional support they need in order to reach their personal goals. Yes, the physical plan is stunning, though it’s more than the views—the buildings, their orientation, their access points underscore the values of the school in, at times, some deceptive yet equally pervasive ways. The school intends to set the standard for education, though all schools perhaps would say the same thing. With the sustainable buildings, the richness of the programs, and the quality of the school community, in some key ways Brentwood, frankly, is doing precisely that, and its reputation, nationally, understandably continues to grow.