Chisholm Academy THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Chisholm Academy, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Our Kids editor speaks about Chisholm Academy

Introduction

Chisholm Academy is a private school for students who could easily get lost in the shuffle at public schools, yet aren’t suited to the rigorous, enriched academic programs offered by many private schools. It is a perfect setting for students struggling with learning disabilities, ADHD, general academic weaknesses, and mental health concerns like anxiety and depression. It is also ideal for parents who have spent years searching for resources to help their children achieve their full potential. The school provides an individualized, structured education in a highly supportive environment designed to rebuild students’ confidence and nurture their abilities.

With roots in an educational psychology practice, Chisholm’s teaching philosophy views students’ emotional health as pivotal to their learning capacity. “We come at the whole school experience from a unique angle, in that our priority is to create an environment where kids feel comfortable,” says executive director Dr. Howard Bernstein, the clinical psychologist who founded Chisholm. “Students who’ve had a difficult time in school don’t love it. They don’t even like it very much. Some of them have been teased and bullied. When they come here, we make them feel good about who they are. They see they’re not alone. Feeling good is the fundamental starting point for learning. There’s an overarching focus here on wellness and providing for all of the kids’ needs, well beyond just academics.”

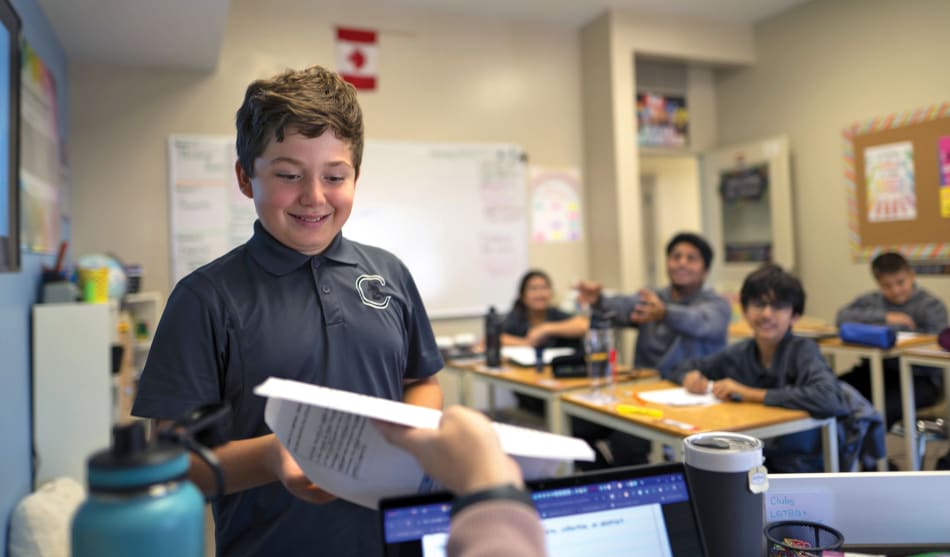

There’s also a focus on fostering strong social skills, since they may also be lacking—or underdeveloped—in some students. “As a small school, we’ve created a close-knit community where we understand every student’s needs,” says Principal Sylvia Moyssakos. “We make them feel welcome and cared for every day. We also organize a lot of school-wide events to promote their sense of belonging. It doesn’t take long for students to make friends and feel accepted here. It’s amazing to see them flourish.” Our visit revealed a school with a warm, welcoming, and relaxed environment. “It’s a family-like, informal, yet respectful place,” says Vice-Principal Graeme Schnarr.

Chisholm calls itself “The IEP School” because every student has an Individual Education Plan (IEP). In theory, these plans—well known to parents of students who have had learning difficulties—are meant to lay out the specific support, accommodations, and strategies that meet learners’ unique needs. In practice, IEPs aren’t always fully implemented due to large class sizes, stretched resources, and lack of special education expertise. At Chisholm, everyone we spoke to asserted that they write exceptional IEPs that teachers not only follow, but regularly revise to align with students’ evolving strengths and challenges. “Our teachers use the IEPs on a daily basis to ensure that students are receiving accommodations and modifications based on individual student needs. Teachers make the IEP part of their teaching philosophy in order to provide special education support. Our teachers use the IEP document as a foundation along with their naturally kind and caring personality,” says vice-principal and head of special education, Farhana Shaheed.

Teachers all have at least the first level of Ontario special education certification. Mentoring and professional development are ongoing, in recognition of the constantly evolving research in neurodiversity, youth mental health, and special education. Forging strong teacher-student relationships as a way to maximize learning is a top priority at Chisholm. There are two child and youth workers on staff to provide additional support both inside and outside the classroom.

While the school casts a fairly wide net in terms of the special education needs it can and will support, there are limits, says associate director Adam Bernstein who handles admissions, business operations, and—occasionally—counselling. “We can’t accept students whose primary diagnosis is behavioural,” he says. “We’re just not equipped to manage those needs. But we fully understand and expect that our students will sometimes have frustrations that can lead to problematic behaviour. We’re not a zero-tolerance school when it comes to reasonable teenage mistakes. We believe in second chances here.”

To be considered for admission, students require an up-to-date psychoeducational assessment. If it’s more than two years old, parents must get a new one at a clinic of their choice or at the affiliated Chisholm Psychology Centre. Admissions personnel also provide recommendations for psychologists in the wider community.

About 75% of the school’s graduates go on to college, and 25% to university. More than 90% are accepted into their preferred post-secondary programs. In line with these outcomes, Chisholm offers mostly applied-level courses in high school, with a good selection at the academic level. A co-op program in Grade 11 and 12 is very popular among students seeking real-life work experience. Extra academic support is readily available, including teacher-supervised study halls at lunch and after school. TA support and one-on-one courses are also available for an extra fee.

The wide variety of inclusive extracurricular activities are part of the school’s broad efforts to cultivate emotional resilience and self-esteem in students—and to show kids who have previously had a negative school experience that school can be joyful. Athletics are for promoting health, self-image, and community, with competition restricted to intramural play.

Chisholm is a rare breed of private school with few competitors. Dr. Bernstein rejects the idea that his students are anything but regular kids who happen to learn differently. Our visit—where we had the pleasure of meeting a group of friendly, bright, thoughtful students from across the grades—confirmed this fact. “Drop by here and you’ll see great kids doing their best at school and at life,” he says. “We make this possible by providing an environment that makes them feel safe, important, and happy.”

Key words for Chisholm Academy: Support. Dedication. Care.

Basics and background

Chisholm Academy is a private, coeducational day school for students with special education needs in Grades 7 to 12. It’s small—limited to 135 students—and has small classes— 12 max, and some are half that size. Located in east Oakville, Ontario, Chisholm is surrounded by retail properties and there is a residential neighbourhood between it and the nearby lake. The 25,000-square-foot space is three storeys at its tallest, and the architecture could just as easily lend itself to a high-end office building. There’s a circular drive for easy drop- offs and pick-ups, an inner courtyard, and a green field behind. Chisholm Academy is also a not-for-profit organization with charitable status.

“We were fortunate to be able to build it from scratch when we opened about 20 years ago,” says Dr. Bernstein. “It doesn’t look like a traditional school, which was intentional in that it’s not at all intimidating.” There are two entrances to the building: one to the Chisholm Psychology Centre and one to the school. Once inside, you’ll see small classrooms purpose-built for an intimate learning environment. The younger grades have most of their classes on the upper level, while the high school students populate the main floor. Student artwork lines the hallways, and the compact size of the whole place creates a friendly, cozy feel. Looking ahead, a new, full-sized gym will soon be under construction and there are plans for a new drama studio to accommodate the very popular drama program.

One unique ritual is the ringing of a big old-fashioned bell, the kind that you’d find in 19th-century schoolhouses. Dr. Bernstein discovered it at a barn in southeastern Ontario and had a bell tower built at Chisholm. “Every morning now, a student rings the bell to start the day,” he says. “They all take turns. It gives us a sense of tradition, stability, and belonging. You can’t help but smile when you hear it.”

The school crest, a sailing ship that looks to be in a strong gale, reflects two aspects of the school. First, of course, it’s located in a lakeside town. The second meaning is metaphorical, according to Dr. Bernstein. “We help guide students through turbulent waters, teach them the skills to stay afloat, and offer them safe harbour when they need it.”

Chisholm’s origins go back to 1971 with the creation of a tutoring centre, one of the first of its kind in the region. It grew quickly over the decade and the founders decided to hire an educational psychologist. They asked Dr. Bernstein, who was working at a hospital at the time, to come on board. “I wanted to get back to working with youth,” he says. After he joined the centre in 1980, the psychology practice grew quickly by concentrating on providing psychoeducational assessments. Soon after, he bought out the founding partners. The name Chisholm, by the way, comes from Oakville’s founding family.

Back then, standard practice was to provide psychoeducational assessments only to schools and health care professionals—not parents. Dr. Bernstein strongly disagreed with this convention, so he changed it. “When I started giving parents access to the assessment, I took some heat from my colleagues in the field,” he says. “But I knew it was the right thing to do. And now it’s the norm.” As his psychology practice grew, he started to see demand in the tutoring centre for more intensive, curriculum-based instruction. In response, he began hiring teachers—including current principal Sylvia Moyssakos—to teach Ontario ministry-certified credit courses to individuals or very small groups of students.

By the late 1990s, more and more parents were asking for a full-time program with small classes and comprehensive support, something they couldn’t find in the public system. Dr. Bernstein, never one to shy away from a new adventure, decided he’d start a school to bridge this gap in the system. In 1999, Chisholm Academy opened its doors to about a dozen Grade 9 students. “We started small and added a grade each year, and here we are today,” he says.

Leadership

The two people at the helm of Chisholm were there well before it became a full-fledged school. Dr. Howard Bernstein and Principal Sylvia Moyssakos—a seasoned psychologist and veteran educator—have complementary expertise and personalities. While he’s known for his sense of humour and she’s known for her poise, they appear to enjoy the same great respect and affection in the school community.

Dr. Bernstein is a natural storyteller, and the tale of how he arrived where he is today is a compelling one. “I grew up in a traditional working-class family,” he says. “My dad was a meat cutter and my mom was a housewife. But it was a pretty difficult home life for me, so I left in the tenth grade. Over the next few years I worked in factories, supermarkets, construction, truck-driving— you name it. Eventually, when I was 19 or 20, I got a job in a juvenile detention home. It changed my life. Some of the kids had a veneer that was tough, but I came to see that they were mostly nice kids who were trying to cope the best way they could. I also saw what a huge difference the right kind of support could make in their lives.”

That experience inspired Dr. Bernstein to go back to school with the aim of attending university for psychology. Once he became a registered educational and clinical psychologist, he worked for hospitals, school boards, and clinics in Canada and the United States. “I did just about everything you can do in psychology, but I was always pulled back to working with kids,” he says. “It’s my passion because you can really make a difference with them.”

As someone who went through harsh times and felt alone as a young teen, Dr. Bernstein empathizes with Chisholm students. “My early experience is the greatest influence on what I do now, and how I do it,” he says. “I tell my students that the hardest things in life can lead to the greatest growth.”

Lorna Hughes, Chisholm’s admissions officer and HR coordinator,

says Dr. Bernstein is like a father figure in the school community. “He has so much knowledge and expertise, but also a personal understanding of how it feels to be a teenager having a rough time. For parents, they know they’re in good hands because of his professional background. They know that they can trust him when they have concerns, and he makes himself available immediately.”

The Chisholm teachers we spoke to appreciate Dr. Bernstein’s down-to-earth manner and warmth. “Right from the first time I met him when I was interviewing, I could tell he was an easy- going guy,” says vice-principal and guidance counsellor Graeme Schnarr. Teacher Yvonne Curic echoes this sentiment, saying she’s never had a more supportive or collaborative administrative team in her career.

Parents agree, with one commenting, “As soon as I started talking to Howard, I could tell he really knew his stuff as a child psychologist. But he’s also a real person and he doesn’t try to confuse you with technical knowledge. He talks to you like an equal and is very honest about what the school can and can’t do for your child.” Another reported that there was “lots of laughter” in her first meeting with him, alongside straight talk. Several parents say Dr. Bernstein was the first school administrator who was genuinely open to hearing—and implementing—their ideas about how their children learn best. “In the past, I’ve been called an ‘enabler’ of my son’s anxiety because he’s very attached to me and often needs me to be around. Dr. Bernstein wanted to hear why I wanted to take the approach of easing my son into Chisholm one class at time, with me being available when he needed calming. He agreed, and the whole process was a true partnership.”

As for working with his son Adam Bernstein, associate director of the school, Dr. Bernstein says it’s a positive and productive relationship—despite the fact that he never intended to work with family. Seeing them together, it’s obvious that their good-natured ribbing is integral to the lighthearted environment. “His experience in mental health counselling is ideal for Chisholm, and the kids love him because he has an inner teenager like me,” says Dr. Bernstein.

Principal Moyssakos also cares deeply for the students. In 1993, she joined the learning centre that was a precursor to Chisholm Academy as a teacher in the individualized credit program, then became coordinator of the tutorial and remedial program.

When Chisholm became a full private school, she was a science and math teacher, head of special education, and vice-principal before becoming principal in 2019. Her qualifications are impressive: an MBA in addition to specialist designations in special education, guidance, and principal qualifications. “I wanted to ensure I had all the information and all the knowledge to be able to help students meet their educational and career goals,” she says.

In our interactions with Moyssakos, she spoke with admiration about her students’ capacity to thrive despite whatever obstacles they confront. “We focus on the whole student at Chisholm, not just their academic aptitude. Our philosophy is to help them see their other strengths and talents.

I’ve learned so much from them over the years. They’re kind and perceptive, they help each other and build each other up, and they have so much to offer the world. According to Hughes, Moyssakos is a quiet, reassuring presence in the school. “She has this calming influence on the teachers and students. She’s been here a long time, which also brings a huge amount of trust with our staff and parents.” In Curic’s words, Moyssakos is “a leader extraordinaire. She has the most positive presence across the school, and everyone—students, teachers, parents—feels they can go to her with anything.”

Academics

At Chisholm, the whole academic program hinges on each student’s IEP. The prevailing conviction at the school is that a thoroughly individualized approach to learning, coupled with small class sizes and extensive support, sets up each student to achieve their personal best. In our observations and interactions with staff and students, it’s very apparent that Chisholm has developed a streamlined, successful method for managing 135-odd IEPs. “I have a documented model of everything that the students are capable of achieving and of their various needs and strengths as learners. I develop all of the IEPs for the students and I work on this fluid document throughout the school year to make sure it is an accurate reflection of what the student is capable of,” says Vice-Principal Shaheed.

There are regular IEP review meetings coordinated by Shaheed. All IEP review meetings include the principal, two vice-principals, psychology staff and every teacher who interacts with a given student to determine how well the plan is working, which learning strategies could be added or removed, and which accommodations are proving most effective. The accommodations could be anything from providing extra time for assignments to breaking down information into more manageable pieces or “chunks.” “We believe that an IEP is not a static document that you write once in a child’s life and it follows them through,” says Adam Bernstein “We treat it as a fluid, living, breathing document that changes as a student matures and develops.” Shaheed adds, “I love being able to see positive change in students and knowing that being in an environment with a tailored teaching approach ensures that students are getting the support that they need to be successful in their individual ways.”

For Curic, who teaches a range of traditional high school courses in addition to specialized nutrition classes, the IEP is a crucial foundation, but she says constant interaction with students is key to ensuring truly individualized education. “In such a small school, we have time to closely observe our students and have lots of good conversations every day, which allows us to constantly assess where they’re at and what they need. We get to know them so well that we understand exactly what they need to succeed. I do my lesson plans 8 or 10 different ways. It sounds like a lot, but it’s just the way we do things, and it works so well for our students.”

Several parents we spoke to commented on the “one-size-fits-all” approach to students with learning challenges at their children’s previous schools, comparing it to the highly individualized attention offered at Chisholm. One parent of a recent graduate says, “My son didn’t fit in the special ed sector in his high school, but he needed more support than was provided in the mainstream. He was right in the middle, and it just wasn’t working for him. At Chisholm, every teacher knew exactly how to give that little bit of extra help that allowed him to thrive.”

Our discussion with students revealed that they’re very aware of how they benefit from individualized instruction. “At a lot of other schools, they think everyone learns the same way,” says one Grade 10 student. “At this school, you can find the answer to a question whichever way makes it easiest for you, and at your own pace.” Says another, “They do different learning styles here. Some kids learn better when the teacher does a lesson, but some like to read and do the work on their own, or maybe watch a video like a TED Talk.” We think this Grade 11 student sums it up best: “They helped me find that key that would open the lock to all that knowledge hidden inside my brain that my last school couldn’t find. I’ll be forever grateful for that.”

In Grades 7 and 8, the focus is on remediation in reading, writing, and math. Assistive technology is integrated throughout the academic program. For example, every Chisholm student receives a Chromebook with Google Read & Write, software that provides support such as text-to-speech and speech-to-text tools. In addition to the core curriculum and preparation for secondary school, there’s a course on social skills that formalizes instruction on building healthy relationships with peers, adults, and, ultimately, society at large.

In high school, three-quarters of Chisholm students take courses at the applied level. Instead of French, every Grade 9 student takes a learning strategies course that fosters crucial skills such as time management and test preparation. Students take an extra literacy course in Grade 9, which offers more intensive preparation for the provincial literacy test that’s required for graduation. In Grade 12, there are two unique offerings to note. The first is a popular co-op program, and the second is a recreational leadership class, where students learn to plan and execute events—including one for younger students at the school and one school-wide celebration.

Beyond the core support of carefully constructed and diligently implemented IEPs, students can attend daily study halls at lunch and after school. Run by teachers, these optional sessions are a convenient way to access extra help in a group setting.

Pedagogical approach

The Chisholm leadership team is extremely selective in faculty hiring, though the teachers are a diverse group. Some have decades of experience, while others are freshly minted. Some have only the baseline special education training, while others have achieved full specialization. But they all have one thing in common, according to Dr. Bernstein, and that’s what he calls “heart.” “It’s the one skill you can’t train teachers in, and it’s a must-have here. Teachers have to want to really connect with our kids, to dig deep and truly get to know them so that they can see the early warning signs when they’re about to shut down or give up. We hire teachers who have that drive and dedication.”

Several teachers we spoke to pointed to the teachers who have been at Chisholm for almost as long as it’s been open as proof of the school’s exceptional working environment and dedicated staff. “When I interviewed here, I immediately noticed that there were teachers with long tenures, which tipped me off that there must be something good about this place,” says Schnarr.

Physical education teacher John Mooney says he initially planned to stay at Chisholm for a year or two to launch his second career in teaching, and now he knows he’ll retire there. “This is a place where teachers have a real chance to make a difference with kids. I get so much joy out of learning about them as people and finding out what they need to learn best. You can only do that in a small school that focuses so much on building teacher-student relationships.”

In addition to individualized education, the school’s teaching philosophy is founded on the premise that students—especially those who have felt unsuccessful in school—can only reach their full academic potential if they trust their teachers. “When kids who have been apprehensive about school in general see that their teachers value their ideas and opinions and care about them as human beings, they feel worthwhile and competent,” says Adam Bernstein. “It doesn’t mean their learning disabilities go away, but they’re just bound to do better academically.”

The teachers, parents, and students we spoke to agreed that the faculty’s “relational” approach, where caring and trust are the foundations for teaching, is the foundation for success at Chisholm. “The single biggest thing that all my colleagues share is that we truly care about the kids,” says Mooney. Parents feel that care and couldn’t say enough to us about how far the teachers go to show it. “They constantly pick up the students when they’re feeling down,” says one parent. “They’re always boosting the kids’ confidence by taking a genuine interest in their lives inside and outside the classroom.” According to another, “The teachers helped make my daughter feel better socially and emotionally, which made her more motivated to learn.”

Most telling for us, however, was how the students spoke about their teachers. Says one, “They’re very patient and spend time with you to help you with your work or give you extra days if you’re having a hard time. It helps to make you feel so much calmer.” A Grade 11 student says, “They try to learn about every kid and their individual learning style, and they’re just passionate about it.” Another student describes the balance between support and autonomy. “The teachers always have your back, but it’s not as if they’re always holding your hand. They teach you how to be independent, too.”

In addition to this emphasis on teacher-student relationships, Chisholm takes a structured—yet active and flexible—approach to teaching. “Our students benefit from having very clear expectations about how classes operate and what they need to do from day to day,” says Moyssakos. “Whenever we introduce new concepts, it’s never just theoretical. We ensure there’s a practical, active component to it by providing real-life examples and applications. There’s also a lot of latitude around how students demonstrate their learning. Based on their learning styles, some students might write a blog while others could shoot a video or create a website.”

Chisholm teachers recognize that consistency reassures students coping with any type of anxiety. Simplicity and predictability are key to the school schedule. Every day has four classes lasting 70 minutes. In Grades 7 and 8, the first three periods remain the same each day of the semester and only the last period changes depending on the day of the week. “It’s very user-friendly, and my daughter loves knowing what to expect every day,” says one parent. High school teacher Yvonne Curic says, “I always let my students know what the current and longer-term plans are, and I like to start each class with an activity that eases them in.” On the day we visited, the white board in Curic’s food and nutrition classroom was covered in doodles from the previous class. “Drawing is not only a soothing activity, but it brings them together as a team to create something and builds social bonds.”

Chisholm teachers are always collaborating, most often to compare strategies for students with similar learning challenges. “They’re continually coming up with new ideas and trying different things to best serve our students,” says Adam Bernstein. The school’s two child and youth workers (see below) are integral to the teaching team, providing mostly non-academic support that enables students to maximize their learning.

Strong collaboration among the entire staff enables everyone to get the most complete picture of individual student’s needs and strengths, and to create the most up-to-date and comprehensive IEPs. “When one of us has a student who’s not keeping up or having issues we can’t resolve, we get together and share our knowledge of that student, maybe from previous years, along with any insights from students with similar challenges, and we figure out a plan together,” says Curic. “All the information goes into students’ IEPs, so we know every staff member who interacts with them has the same knowledge and can provide the same level of individualized support.”

For more formal professional development, the school provides workshops, seminars, guest speakers, and courses on all aspects of special education, adolescent mental health, and neurodevelopment. The affiliated Chisholm Psychology Centre sometimes delivers educational sessions on topics that emerge in the wider social context, such as the rise of anxiety during the pandemic. Several teachers say they sometimes consult the centre’s psychologists when they need expertise on specific learning challenges or mental health concerns.

“Our teachers are not just teachers,” says Dr. Bernstein. “They’re mentors. They’re compassionate, trusted adults in the lives of kids who need that more than most. They understand what it looks like when kids get anxious or frustrated, and they know how to diffuse escalated situations so that everyone can get down to learning.”

Social skills

Whether Chisholm students are in math class or out on the field for gym, they’re learning non-academic skills that are essential to success inside and outside the classroom. The school takes a very intentional approach to developing students’ ability to manage themselves in all types of social situations. Managing conflict, respecting different opinions, communicating effectively, regulating emotions—these crucial skills are integrated across the Chisholm curriculum.

In our discussions with students about the culture of respect at the school, several recited a motto they hear each morning on the announcements: “Treat everyone with dignity, equity, and respect.” Asked how students learn to treat each other with respect, one student says, “We learn it everywhere, from other students, teachers, the principal, even the custodial staff.” Another says, “It’s like the school has a spirit of its own that tells you to treat everyone with respect.”

Every teacher we spoke to emphasized the vital importance of trust and communication in fostering social competence. “We take the view that the social part of school is as important as the academic part,” says John Mooney. “I create an environment where they know they can take chances and have opposing viewpoints, and nobody will ridicule or punish them. By building that trust, I show them that I’m open to their ideas, and they can talk about what’s on their mind. Learning how to share their thoughts in conversation, and understanding it’s a give-and-take process, is such an important skill. So I give them lots of space to just talk, knowing that they’re gaining social confidence and new capacities.” Curic agrees, saying “conversation is such a big part of students’ learning at Chisholm. Just being there to listen when they need to talk is huge.”

Grade 12: Leadership and nutrition classes

Since Chisholm students have all dealt with some kind of academic and/or social adversity, Grade 12 is an especially important milestone. To recognize its significance and arm them with the skills they need for whatever comes next, the school has two courses in the final year focused on leadership and nutrition.

“We thought about what essential capabilities our students would need when they graduate, and these two topics were obvious,” says Mooney. He’s been teaching the recreational leadership class for the past six years. It’s a hands-on course where students take the reins—with some guidance from him and other teachers—in planning, organizing, and executing several school-wide events. “It starts with them brainstorming ideas and learning to integrate everyone’s thoughts on how to run a fairly significant event,” he says. “One recent example was the Terry Fox Run, where the kids did everything from advertising and reaching out to parents to planning the entertainment and refreshments and accounting for donations.”

Other events the students take the lead on throughout the year include holiday-themed celebrations and charity campaigns. They must also devise original games to teach the Grade 7 students and run special games days. “It gives them an opportunity to contribute something to the greater school community, and it brings them together socially because they’re working closely to ensure their plans are successful.”

Curic, who grew up in the family restaurant business and previously owned a catering company, teaches the Grade 12 courses on nutrition and health and another on food and the workplace. “I love these classes, because they combine my two passions—teaching and cooking,” she says. On the day we met with Curic, she had just finished baking homemade multigrain pizzas with students in an improvised barbeque pizza oven outside. Curic says the food-based classes not only teach students the practical skills required to cook healthy meals for when they start living on their own but also draw on math and language skills in following recipes and decoding nutrition labels. “We have a lot of fun, but the kids come away with really valuable knowledge that every high school graduate should have.”

The Grade 12 class is split into two cohorts for the leadership and nutrition courses, but Mooney and Curic make a point of bringing the whole class together regularly for informal conversation. “We want them to feel a shared pride and sense of community in reaching this stage of their education,” says Mooney.

Post-secondary preparation

Just over 75% of students from Chisholm go on to attend college and 25% go on to attend university, so vice-principal and guidance counsellor Graeme Schnarr spends much of his time exploring pathways for this cohort. This doesn’t mean that he isn’t equally dedicated to those headed to university, or the small minority moving directly into the workforce. All the students and parents we spoke to praised his ability to find the right program for every student—taking the same individualized approach that underlies every aspect of the school’s operations. Schnarr, who has a master’s in education, notes that in Grade 10, Chisholm students start required guidance courses to learn about the post-secondary system and future careers. A Grade 11 course that’s an elective at other schools, “Designing Your Future,” is mandatory. “By the time they get to Grade 12, every student is pretty well-versed in the system and its pre-requisites,” says Schnarr. “They’ve also had a lot of time to examine their strengths and interests. In Grade 12, I meet with everyone one-on-one several times to home in on exactly what path is most suited to them.” The students we talked to say they feel good knowing the school helps them chart a path. “I have faith that the guidance classes and Mr. Schnarr are going to help me figure out what I want to do,” says one Grade 11 student. “He gives us lots of advice and suggestions.”

Schnarr also meets with all Grade 12 parents, and parents of students from any grade with questions about the future. “It’s so reassuring knowing that he’s on top of all the different routes to post-secondary for my daughter,” says one parent of a Grade 10 student. “The peace of mind is immeasurable, and I have a much more optimistic view of my daughter’s options than before she came to Chisholm.”

Wellness

We observed broad recognition within the Chisholm community that students who have struggled in school, for whatever reason, require extra social and emotional support to regain their academic confidence. It’s very evident that this is a school founded and led by a clinical psychologist. The staff all seem to share a unique vantage point that combines an educational and psychological perspective.

“The environment is very nurturing,” says Moyssakos. “We spend a lot of time building students’ feelings of self-worth through spirit days and extracurricular activities. We also do this simply by giving them a sense of being part of a caring school community.” The school’s extra attention to students’ social and emotional health begins before their first day of school. All new students, whatever their grade, start school a couple of days earlier than everyone else in September. “It’s all about easing their transition,” she says. “Sometimes, when kids have been unhappy at their old schools, it’s hard to get them in the door here. We want to give them extra time to get accustomed to the building and their teachers. For students with anxiety, that transition can be even longer and more gradual. They might just get to the parking lot the first day, then take a peek in the door the next. We’re very accustomed to accommodating these types of situations.”

The parents we spoke to were effusive in their gratitude for how the school welcomed their children—who had all experienced bullying, exclusion, self-isolation, or all three—and, in a sense, brought them back to social and emotional health. “My son was lonely, withdrawn, and didn’t want to go to his old school,” says one parent of a recent graduate. “Within a week of starting at Chisholm, he couldn’t wait to go to school. We began to see an entirely new sense of confidence and maturity in him. Moving him there was the best thing we’ve ever done for him.”

The students who met with us talked openly about the relief of feeling accepted and secure at school. According to them, the school’s zero-tolerance policy on bullying is real—not window-dressing, as in some of their previous schools. “The teachers absolutely do not tolerate it, because a lot of the kids—me included—came here because we were bullied,” says one high school student. Another says it was a somewhat disorienting experience at first. “I didn’t know who I could trust, and I didn’t want to talk to anybody at first. I was confused because everybody was so nice. Then I got used to the idea that this was a regular feeling—being safe and comfortable.”

Everyone we spoke to in the Chisholm community had a story to demonstrate the extraordinary changes students undergo after coming to the school. “We see massive changes in students,” says Curic. “It’s like night and day compared to when they arrive. They might be very quiet and withdrawn at first, not speaking to anyone, and then I see them again and they know everybody and are chatty and at ease. It just takes them a little bit of time to get used to the fact that they’re safe here and no one’s going to put them down.”

Staff members monitor not just students’ academic performance, but their overall welfare and mental health. “We’re constantly looking for any signs that kids are in distress, so we can address it quickly,” says Adam Bernstein. “We want kids to have positive days where they’re able to do as much learning as they can with the least drama possible. Their brains process things in a different way, and by the end of the school day they’re exhausted. So the more that we can do to make them feel comfortable, the better off they are.” The students we met confirm that they feel this concern and attention. Says one, “They can always tell when you’re having a hard time and will ask you about it to see what might help.” Another comments, “You can tell your teacher if you’re feeling down, for example. They want to know how you’re doing. It kind of makes it feel like you’re talking to an actual person and brings us to the same level.”

Recognizing the range of social, emotional, and learning challenges Chisholm students confront, the school’s approach to discipline tends to have a “softer touch,” according to Schnarr. “The truth is that we don’t have a lot of discipline issues here, partly because our admissions process ensures that we’re bringing in kids who will abide by our values of kindness and mutual respect. We also have in-depth knowledge of students’ triggers and the strategies that calm them. If a student’s having a bad day and is acting out, instead of laying down the law we get them to take a break in a quiet space like a child and youth worker’s office or take a walk to decompress.”

On our visit, we heard a lot of laughter, both in students’ interactions with each other and with their teachers and administrators. Says one parent, “Spending time at the school, it becomes obvious that the teachers are always trying to make learning fun and relatable to everyday life. I know for my son, if everything is boring and serious all the time, he switches off. Also, the school tries to keep things light to avoid giving the children any more anxiety than they might already have.” Another parent agreed, saying, “My daughter thinks the teachers are so much fun. She still doesn’t love every subject and learning can be challenging for her, but she loves going to school.”

Mooney says he and his colleagues are united in their goal to bring joy into the daily life of the school. “Seeing smiles on kids’ faces is something we all work toward. We know they’ve all had a tough time in some way before coming to Chisholm, and making them feel safe and happy is as important to us as the actual teaching, because they can’t learn when they’re feeling bad. One of the things that almost all of our students lack when they arrive here is confidence. Once they’ve been here a short time, feeling the acceptance of students and teachers, they realize they’re as good and worthy as anyone else and are ready to learn.”

To our knowledge, Chisholm is the only private school with an affiliated psychology practice. It’s a valuable resource in several ways. The psychologists help develop students’ IEPs, provide consultation to teachers, and offer counselling to students and parents on request (for a fee). Having two child and youth workers (see below) on staff is also unique and advantageous to this student population. “You often hear teenagers, especially those who are dealing with learning or mental health challenges, say that adult don’t understand what’s happening in their brains,” says child and youth worker Kyla Parsons. “But at Chisholm we do understand, and students sense that. We also empower them to understand how their own brains work. We take the attitude that we all have certain roadblocks in the ways we learn and see the world, but we can find detours and new ways to get where we want to go.”

Child and youth workers

There are two child and youth workers on staff at Chisholm who work alongside the teachers and administrators to support students. “They’re very involved in the kids’ daily lives,” says Moyssakos. “They run clubs and sports, but they’re also available on a one-on-one basis when students need someone other than a parent or teacher to talk to. Their offices offer a nice, quiet space when students need to get away.”

According to Parsons, her tasks and responsibilities all boil down to being a caring adult who isn’t a teacher. “Often a student may be having a difficult day and just need a quiet place to calm down, or we’ll take a walk outside,” she says. “Sometimes teachers call me into their classrooms to help or implement strategies to alleviate a student’s anxiety. Other times I might work with students on their assignments. I also meet once a week with a set list of students who are coping with ongoing challenges so I can check in on how they’re doing. But my door is always open to any student.”

The child and youth workers also help deliver social skills education through guidance classes in Grades 7 and 8 or through individual programs. Parsons leads a twice monthly group for Grade 7 and 8 girls, who get together to chat and explore subjects such as healthy conflict, social cues, and female friendships. “Since participating in these gatherings, I’ve noticed big changes in my daughter’s willingness to approach girls and form new friendships,” says one parent.

According to several staff members we spoke to, one of the child and youth workers’ most crucial roles is keeping tabs on how well students are functioning from a psychosocial perspective. “They’re very good at identifying which kids might not be making friends and who are spending a lot of time alone,” says Adam Bernstein. “They find really creative ways to draw students out and connect them to people and activities that will improve their soft skills.”

The teachers we spoke to all emphasized the importance of students having an equally positive, but different, relationships with teachers and the child and youth workers. “It’s so beneficial for the kids to be able to say to us as teachers, I need a break from you and this classroom, and to know they always have another person to go to who understands,” says Curic.

Both child and youth workers lead several clubs and sports, which gives them another way to gain insight into students’ overall well-being. “Our relationship with students is slightly more relaxed than their relationship with teachers, but it’s still based on mutual respect,” says Parsons, who runs the mindfulness and LGBTQ clubs, among others. “The whole school is built on relationships because it allows us, as the adults, to understand exactly what each student needs to feel safe and good at school. It also helps us understand what students need in their most difficult moments.”

The child and youth workers are tightly integrated with the teaching faculty, participating in all professional development and contributing to IEP meetings. “We’re a close-knit team because we want to make sure we’re all on the same page and we all have the same tools in our toolkit to work with students,” says Parsons.

Co-curricular activities

For a small school, Chisholm offers a wide range of clubs and activities, which mostly run at lunch for maximum accessibility. The school community is especially proud of its drama club, which puts on two productions each year. Soon there will be a new drama studio for club members. “You might not expect that kids with learning and memory issues and anxiety disorders would be inclined to join a drama club, but what they create together is amazing,” says Dr. Bernstein. “Some of our productions have even won awards, which makes the kids feel so good about themselves. And that’s what we’re all about here.” According to one parent of a Grade 8 daughter—who was painfully shy at her old school—

discovering drama and its accompanying social life was transformative. “It was like she was a wilted flower that got watered.”

Sports are an important part of student life at Chisholm, but any competition is internal. Many intramural teams contain students from across the grades, further building strong community bonds. Mooney runs many of the sports clubs that run at lunch and after school. “Our intramurals are incredibly popular,” he says. “Over the course of the year there’s always a team to join, from ultimate frisbee to basketball and flag football. Every lunchtime we’re out there playing something.” A soon-to-be-completed, full-sized gym will enrich the current athletic facilities, which consist of an outdoor basketball court and large back field.

Teachers often take the students to nearby baseball fields and arenas. For students who aren’t interested in sports or drama, there are plenty of clubs catering to a wide variety of interests. Run by teachers and the child and youth workers, they run the gamut from robotics and IT clubs to photography and mindfulness groups. The movie club—where students simply go to a local theatre to watch a movie together—got rave reviews from the students we met. “We prioritize extracurricular outlets because they’re just another valuable opportunity for our students to interact with their peers outside the classroom and gain important life skills,” says Mooney.

Student population

Students travel from most parts of the Greater Toronto Area to attend Chisholm, an indication of how unique it is in the private school landscape. Busing is available from the Toronto/Etobicoke and Burlington areas. “We’ve had families move to Oakville to allow their child to come here,” says admission officer Lorna Hughes. The downside, of course, is that students sometimes have to work harder to maintain their in-school friendships outside. “My son has made wonderful friends,” says one parent, “but a lot of them don’t live locally, which is a shame. We make it work, though.”

Still, Hughes is frank about the fact that, in her dealings with prospective students, she hears some say that they don’t want to go to “a special school.” She reassures them that it feels like any other school, just with kids who happen to learn a bit differently or need some extra support. “I tell them that the only difference is that they’ll receive the help they need to make learning less painful and more successful. Most of them feel huge relief when they get here and understand that, like them, everyone is there for a reason. But it all looks and feels very ‘normal.’ Many students feel like they’ve finally found their people.”

Several Chisholm community members used the same phrase—“everyone is here for a reason”—to explain the sense of belonging students feel, and the compassion they extend to their peers. “Because of their various needs, a lot of our students will have encountered bullying or stigma before—whether that’s somebody else bullying them, or whether it’s internalizing the feeling of not being good enough,” says Schnarr. “Somebody else’s reason might be different from their reason for being here, but students can empathize with each other.” In the words of one student, “I think we connect so well because we’re all here for the same reason. We want to learn and found that our old schools couldn’t teach us. We understand each other.”

Our discussions confirmed that it doesn’t take long for students to find their place in the Chisholm community. “Instead of asking new students to start participating in everything right away, we let them hang back and observe until they’re ready to join in at their own pace,” says Schnarr. “They see kids like themselves playing sports at lunch, joking with their teachers, and attending clubs, and over time they start to understand that this is a safe place where everyone is good to each other.” One high school student says, “There’s a cool atmosphere at Chisholm that I never experienced at other schools, where the kids aren’t mean. For any kid who’s had trouble being around other kids, this is a good place to be.”

We heard several stories from students about their first days at Chisholm, and how other students went out of their way to make them feel welcome. “I felt very awkward when I started, but then I started to open up when I realized that the kids—even in higher grades—were being really nice to me,” says one high school student. It’s obvious that the culture of acceptance and compassion comes from the top; staff members model it in all their interactions.

Kyla Parsons, one of the two child and youth workers at Chisholm, is relatively new to the school and says she’s been impressed by the cohesion across the whole student body. “I think they’re proud to be part of a place where everyone supports each other.” According to one parent, the absence of cliques and in-groups is evident right away. “Arriving at Chisholm, you can feel that everyone is seen as an equal in terms of their value. It’s like one big family.”

Our meeting with a group of Chisholm students highlighted an extraordinary undercurrent of mutual care among individuals who had very different strengths and challenges. There was no evidence of competitiveness, social hierarchy, or even the kind of subtle judgment so common among teens. After hearing so much about the students’ empathy and acceptance of each other’s struggles, it was plain to see. “I can’t tell you the number of times a student is having a hard time and another student will go try to help them, completely unprompted,” says Mooney. “It’s absolutely genuine.”

Several teachers say they’ve learned to be kinder, more patient, and compassionate from observing Chisholm students. “This place has changed me for the better,” says Mooney. “I tell the kids all the time that they’ve helped me grow. Being surrounded by their open hearts is a privilege.” Curic agrees, “My students have taught me true compassion, true understanding, and true caring.”

School-wide special events such as regular pizza days and fun competitions also foster connections across the student body. “The events bring us all together, everyone from each class, and I think it’s great,” says one Grade 9 student. “People are able to learn more about each other and have fun. Everybody gets along so well.”

Getting in

The admissions process at Chisholm has some unique features that align with its unique offerings. The first contact is always with parents alone. It’s an opportunity to tour the school with associate director Adam Bernstein and admissions officer Lorna Hughes, describe your child’s strengths and needs, and ask questions. If the admissions team thinks your child might be a good fit, they move to the documentation stage. Every prospective student must provide a current (within the last two years) psychoeducational assessment. This means parents may have to arrange for this specialized testing in advance of their application, either at a clinic of their choice or the affiliated Chisholm Psychology Centre. It’s important to note that the school is strictly impartial about where the testing takes place.

In the next step, students come in for an interview, which is as informal and comfortable as possible. “We know that this part of the process could be really stress-inducing for the kids we serve,” says Adam Bernstein. “So, we make every effort to help them feel at ease. Sometimes I’ll connect with the kids online before the interview to let them know it will be a very casual meeting.”

Tuition is on par with other private day schools in the area, but Chisholm offers a number of scholarships for its size and budget. They’re all based solely on financial need and most offer partial tuition coverage. “We don’t want to tell parents that, yes we can help your child with learning difficulties, but only if you have a lot of money,” says Adam Bernstein. There are some tax advantages associated with tuition for private schools designated for special education (claimed under medical tax credits). Extra academic and psychological support is fee-based.

Parents and alumni

Parents at Chisholm all have one crucial common thread: the experience of having a child who struggles in school. The reasons for that struggle are less important than the shared challenges of advocating for their child, finding effective support, and navigating complex systems. “By the time parents find us, they’ve often been through an awful lot,” says Hughes. “They can also be skeptical, because their children have likely had IEPs at their previous school and the plans might not have served them well. Our job is to earn their trust and show them that individualized education can really work in the right environment with the right teachers.”

The largest referral source for Chisholm is current parents. “Families often don’t even know that there are private school options for kids with special education needs,” says Adam Bernstein. “They’re so grateful when they find us and their child starts to thrive. It’s exhausting to see your child suffering and be searching for help. They also find great relief in joining a community of parents who get it.”

The intense relief and gratitude at finding Chisholm was

palpable in our discussions with parents. Many had been seeking support for their children without success for years, not just in the public school system, but also at other private schools. “I remember that after our first parent-teacher meeting at Chisholm, my husband and I walked into the parking lot and cried,” says the parent of a recent graduate. “We’d spent the last decade being told what our son couldn’t do, what he was never going to achieve, and how he’d never graduate from high school. Now suddenly we were being told about all the things he could do, all the positive things about him. And they told us he’d definitely graduate—he just had to go about it a slightly different way than the usual.”

Flexibility with respect to parent involvement is paramount at Chisholm, even if it means breaking the “rules” that traditionally separate school and home life. One parent sits in the school parking lot for the first days and perhaps weeks of school each year so his son can come out to the car, see a familiar face, calm down, and return ready to learn. “It’s very much a cooperative process,” he says. “In the beginning, it blew me away because I’d never experienced that before.”

Parent communication is proactive at Chisholm, and the parents we spoke to said they always feel informed and connected. Whether it’s receiving friendly reminders about special events or, as one parent told us, hearing that their child isn’t quite ready to tackle homework without the help of study hall, the staff stays in close contact.

There’s an active parent council at the school, whose main mandate is fundraising and special events. Beyond that, however, Chisholm prioritizes strong, open communication with all parents. “We keep them firmly in the loop at all times,” says Moyssakos. “Regular family input and feedback makes everything go more smoothly. We rely on parents to tell us when their child is having a hard day so we can provide extra support from the moment they walk in the door, or to fill us in on what makes their child feel uncomfortable and frustrated so we can make the appropriate accommodations.”

Vice-principal and guidance counsellor Graeme Schnarr also maintains strong communication with parents around post-secondary

planning. “I might reach out to parents to suggest a particular college program that I think would be well-suited to their child or ask their opinion about a program a student is interested in,” he says. “We like to be proactive in our contact with parents, unlike at some schools where you’ll only hear from the vice-principal when your child runs into trouble.”

It was obvious to us that Chisholm parents can rely on the school to go the extra mile for them and their children. Dr. Bernstein helps parents connect with the wellness resources they need outside the school, for example, such as finding a child psychiatrist and personally delivering webinars on timely educational or mental health topics.

The takeaway

Chisholm was created to address the needs of the kinds of learners who are prone to falling through the cracks of a traditional education. Special needs is the term we might use, though the definition used at Chisholm admits a broader understanding than we typically grant, including students from across the entire academic spectrum. What they share is a need for a more structured academic experience. The school is headed by Dr. Howard Bernstein, a clinical psychologist. The ideal student is one who requires more than they are able to get from a traditional academic setting, and who benefits from a very structured, personal, planned approach to their education. A robust interface between parents and the school is encouraged, and close communication is ongoing throughout the academic year.