Meadowridge School THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Meadowridge School, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Introduction

Meadowridge grew out of a common desire among a number of families to create a school that was challenging, forward thinking, and based in a set of shared values. Unlike many private schools, it began with a blank slate—everything was an option—and has grown from there while remaining true to the initial vision that the founding families brought to the table. There are no ivy-covered walls, and the school doesn’t bear the weight of some of the private school traditions that those walls represent. Since it was founded, administration has been agile, adept, and tied to the local population and its desires. The community stakeholders have guided its development and continue to do so today. This isn’t a school led by decree, and the recent capital development is an example of that. It’s truly been a group effort, and you’d be hard pressed to find anyone within the school—from the administration, to the teachers, to the students, to the parents volunteering in the library—who doesn’t feel part of the development process.

Meadowridge is known for its experiential education and inspires students to academic achievement through involvement and personal engagement. They don’t just teach art, for example—they immerse students within it, including the school’s on-site collection of works from an A-list of Canadian artists, including Tom Thomson, Kenojuak Ashevak, and Lawren Harris. The campus includes a forest, and links between art and the environment are profound. Likewise, gardens and greenhouses provide an entrée to ecology and biology, and a design lab introduces students to technology and engineering. Those, and other examples, provide a unique balance between didactic instruction and experiential learning.

The buildings sit on a 27-acre campus, with proximity to urban centres as well as a range of natural environments. The campus includes green space, a forest, outdoor facilities, and a campground. Golden Ears Mountain sit off charmingly in the distance. While some schools pride themselves on being city schools, Meadowridge rightly has great pride in being set a bit apart from the bustle of urban life. Nature feels close, and it is. There are bears from time to time, which of course is absolutely typical of the region and a sign of the health of the biome that the school sits within. (“The school is very careful about that,” says one student, “and we have designated procedures. And they have announcements, like ‘okay, there’s a bear, guys. Come in.’ And the teachers blow whistles.’)

A creek runs through the campus, and it is rightly seen both as an environmental and instructional resource. Six years ago, a Grade 4 class released 5,000 coho salmon fry into it (the creek once supported a population of Coho, though it no longer does). Six years later, the same students—now in Grade 10—surveyed the population to investigate why the salmon didn’t return. They concluded that a recent roadway construction created a barrier that the salmon were unable to navigate.

That kind of project is an example of the intentions of the program and how it has been developed over the years of instruction. “We’re seeing repeats, connecting points, for students,” says outdoor experiential ecological education (OE3) coordinator James Willms. “In that case it was the salmon.” Those connections are then capitalized on through detailed, informed instruction. In addition to the biological processes, the staff layered in other aspects of learning and development, including, in this case, those associated with empathy and stewardship. “You start to see that empathy build for that natural space,” says Willms, “with the intent that if they can build that empathy for our space, hopefully it translates to other spaces in the world, whether it’s their neighbourhood or where they’re travelling.”

In terms of its physical plan, Meadowridge doesn’t present like a typical private school. There are regular interfaces between indoors and out, including doorways from each of the Elementary classrooms onto shared instructional spaces (some with roofs, and others, such as the outdoor play areas and teaching gardens, without). Even then, this isn’t an environment that denies the presence of weather. A bit of rain or snow isn’t enough to prevent kids from getting outside, and they don’t shirk from it. The approach is ‘this is our weather; it’s part of our world.’ And, you never know, it might be interesting (and if it isn’t, the faculty has a knack for making it so).

Details like that are telling, and indeed there are many of them. There’s a collegial feel across the grades and roles, and an intentional flattening of the social and administrative hierarchies. The school encourages staff and faculty to make good and regular use of the Fitness Centre, for example, even during the instructional day. A phys-ed class could go in and find a teacher mid-workout, on the elliptical or doing weights. “I think it is really good for kids to see that it’s not just a room for PHE 9,” says Scott Spurgeon, director of athletics. “That in real life, once you’re done school, people still want to get in there.”

Across the disciplines, the leadership of the school consistently takes a long view, intending to educate children for life, not just post-secondary programs. “Many schools see themselves as transactional,” says headmaster Hugh Burke. “They promise ‘If you send your child here, they’ll go to a university.’ But all of our kids go to a university, or a national theatre school, or an art program—they all go on to significant post-secondary programs.” Beyond that, Burke adds, “we want our children to live well. We have them work with others so that they can learn to be social beings and get along with others in a complex world.”

Burke’s leadership is as consistent as it comes, having served as headmaster since 2001. It’s hard to imagine anyone more qualified. He’s taught drama, English, social studies, literature, math, philosophy, and theory of knowledge. He’s taught from elementary to post-secondary to professional development. He’s been a union rep, administrator, co-ordinator, consultant, writer, and CEO. He’s been a member of the Faculty of Education at Simon Fraser University, and he was the first non-Jewish principal of the Vancouver Talmud Torah. He is a past president of the Independent Schools Association of British Columbia (ISABC) and a past member of the Board of the Federation of Independent School Association (FISA).

He brings that wealth of experience to the school with seemingly unwavering enthusiasm. He is clearly revered and is a constant presence throughout the school, and he’s not at all inclined to limit his activity to the admin suite. During an all-staff meeting, he sat to the side of the stage—something that felt more comforting than onerous, particularly given the size of his personality. Whenever he’s in a room, you know he’s there, which gives strength to his leadership. You also sense that he is aware of his own fallibility and that he understands everything should come as the product of a conversation, not via executive fiat. In conversation, he will occasionally lapse into silence—not because he’s forgotten that you’re there, but rather that he wants to think things through before committing to a response. It can be a bit unnerving at first, though you get used to it and even appreciate it. It’s important, after all, and that’s his approach: whether you’re talking about your child, or education more generally, it’s right that all decisions be given an appropriate level of thought.

Burke exemplifies the kind of leadership that the school hopes to instill in the students. It’s “leading from the sideline,” says Scott Banack, past principal of the Middle School and recently appointed as deputy head of school, “rather than being the boisterous, follow-me type of leader.” Initiatives are developed as a team, and good ideas are shared, rather than originating from the top down.

Key words for Meadowridge School: Imagination. Stewardship. Community.

Basics

Meadowridge is a secular, co-educational, independent school located 30 kilometres from downtown Vancouver in Maple Ridge. It is a not-for-profit institution governed by a board of governors. Meadowridge enrols students in Junior Kindergarten through Grade 12 and has offered the full International Baccalaureate (IB) continuum since 2012, when the Diploma Programme was adopted (the Primary Years Programme [PYP] and Middle Years Programme [MYP] were both adopted in 2007). All students follow the IB, and all graduate with an IB education and the provincial Dogwood Diploma.

When families first start looking for a private school, they’ll often ask about the “best” school—the one with the strongest academics, smallest class sizes, or most impressive university placement rate. Given that all schools are good and all have strong academics—they wouldn’t last past a few years if that wasn’t the case—culture is the more telling aspect of a school’s life. How does it posit the learner? What is the relationship between the learner and their peers? With the members of the faculty? What is the relationship that a school has with the surrounding cultures? The surrounding ecology and natural heritage?

Meadowridge began, quite literally, with precisely those kinds of questions in mind. There was a group of parents in Maple Ridge and Pitt Meadows—the school name is a portmanteau of the two—who wanted a different, better option. They were reacting to what was happening in public education. There had been some strikes, as well as a dearth of student spaces in the public board. They also wanted a stronger focus on academics, one rooted in the strengths of the individual learners rather than the deficits. They put out a call for like-minded parents and held a town-hall meeting in a local hotel. Soon afterward, a number of them formalized the plan and, within the course of months, they founded the school. Classes began that fall with an enrollment of 85 students. “It was all very grassroots,” says Christy Kazulin, the director of marketing and communications. “It was kind of like a little red schoolhouse. … The parents were there, shoveling the ground because it was uneven … getting the portables ready.” The portables were purchased from St. George’s School to house a program spanning Kindergarten through Grade 8. It was extended to Grade 10 in the early 1990s, and then again in 1996, bringing the offering through to Grade 12.

There were some difficult times along the way. As with any school, growing pains are a fact of life, and Meadowridge has weathered them well. The administration also capitalized on the benefits of starting from scratch, seeing it as an opportunity, and purposefully designing the facilities and the resources with the mission of the school foremost in mind. Rather than retrofitting a space to a new purpose, the administration was able to work from a blank page, creating the spaces and organizational structure that would best meet their Mission of “learning to live well, with others and for others, in a just community.”

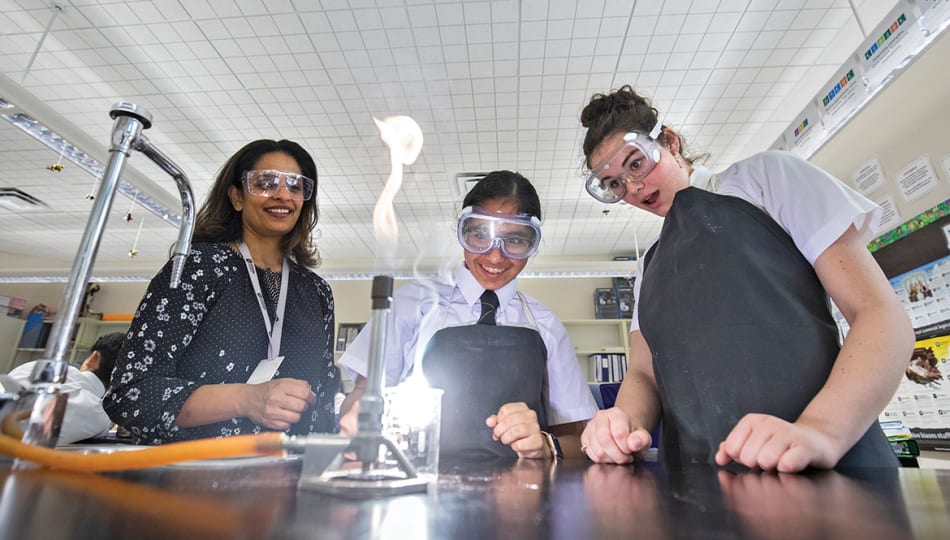

The instructional spaces are varied, dedicated, and stimulating, with ample opportunity to display student work, both finished and in process. In the MYP science lab, one of the walls is decorated with an array of paper bees. “These are bees that have undergone mutation,” says teacher Deepti Rajeev, “so some have an extra pair of wings. We learn about how changes in the DNA sequence will create mutation. And how does that mutation manifest itself? So some bees have two pairs of wings, and some bees don’t have any wings at all. … And we look at the impact of the mutation. Is it a positive mutation? Is it a negative mutation? Is it a neutral mutation?” It’s a charmingly cheerful, busy environment, with lots to look at and, in turn, to think about and interact with.

As in the Elementary grades, the Middle School lab has a door that leads directly outside, something that teachers make good use of. “Every classroom has an external door, and we can often hop over the fence, go for a walk in the forest” during class as well as during advisory sessions, says Rajeev. “We often go for walks. … It is the best place to learn and work.” (“That was probably my favourite class,” said one student of his time with Rajeev in the MYP. “It’s general science. You get to learn about a lot of things—all of the sciences, rather than focusing on one thing.”)

“ ... we think of [Meadowridge] as a garden. Not a garden for children, but a garden of children. Every child, like everything living thing in a garden, needs the conditions for growth that are right for that time.”

—Hugh Burke

There is a flexibility to the property, with additions and renovations happening at intervals throughout the school’s growth. Construction has begun on a new classroom complex which will add nine new classrooms, including a science lab and a science classroom. Glass walls will continue the interface with the property; an open concept and shared spaces will augment the dedication to interdisciplinary instruction.

Academics

Educators Kelly Gallagher-Mackay and Nancy Steinhauser have written that “great schools represent the potential for a more just society and an enriched childhood for every child. They can be engines of universal equality, foundations for strong communities, and vehicles for individual self-definition and advancement.” Great schools are places that will shape and raise expectations, and embrace the complications of families. They build on the students’ strengths, talents, and predilections—working from their assets, rather than their deficits.

The academic program at Meadowridge is based very firmly in that perspective: everyone has gifts, relationships build a community, and curiosity is the seed of learning. Says Burke: “One of the reasons that we have children go outside a lot is that it is good for them right now. And they have fun.” They also experience their world viscerally, intuitively, as messy as it might be. Perhaps most importantly, they begin to formulate a link to the natural world as well as the social world. “We need to understand why water should be clean, where fish come from, how plants grow,” says Burke. “And through an understanding of interdependence with others, they will learn that how we look after the earth matters.”

The development of compassion, stewardship, and an understanding of interdependence is as much a part of the academic program as literacy and numeracy. Instruction is inquiry-based, engineered to ensure that students see the personal relevance and connectedness of what they’re learning. “It’s much more than just academics,” says Kristal Bereza, principal of the High School. “It’s developing confidence, an ability to critically think about things, to be engaged in the world. They move toward a self-awareness … there’s a culture that’s created here that helps them achieve that.”

There’s a nice flexibility in how inquiry and experience are applied within the core disciplines. Rote learning, for example, is understood to have a place, as does lecture-style, didactic instruction. Says Bereza: “it’s about learning the content, but then being able to take it within yourself and analyze it, [so that] it becomes a part of your thinking system.” This is a belief that applying mathematic principles to real-world problems works best when the basics are in hand, such as a facility with the multiplication tables. That kind of mechanical skill development—as well as small-group learning, focused listening, and project-based collaboration—is seen as a tool that has a valuable place within a substantive academic toolkit. “We’re recognizing that education is lifelong,” says Terry Donaldson, director of teaching and learning. “That today is one piece of that lifelong journey. And that everything cumulatively adds up to a person, rather than adding up to an engineer, or a doctor. Life experiences are critically important.”

The academic program is intentionally challenging at all levels. “In that,” says Bereza, “I would say that it challenges each individual for their best. It’s not just about getting the highest marks. It makes you study in areas that may not be your strengths.” As an example, she cites the requirement that all students take a second language all the way to Grade 12 in order to graduate from Meadowridge, whereas it’s only required until Grade 9 in the public system. “They’re not just able to take the subjects that are the easiest for them, or [that they’re the] most gifted in.” She notes that the programming has been developed in order to ensure that students aren’t able to avoid the areas they struggle in, but instead are required to face them. “I think that develops a resilience in our kids, a kind of go-after-it-ness.”

“If they don’t experience some kind of failure,” says Banack, “then we haven’t done our job. Kids learn far more when they fail than when they just kind of cruise through. So it’s about providing those opportunities for the kids to really stretch themselves. … [Putting] them in those challenging situations, with a high degree of support, allows the kids to achieve their best and build confidence.”

“We’re going to stretch comfort zones in all different areas,” says Banack, “and that’s part of the IB as well.” Students spend as much time in arts as they do in math and phys-ed; there’s an engagement in service and an engagement in creativity. That balance is a component of the IB, though it extends what was happening at the school prior to its adoption. The faculty believe that it’s not good enough to just be really strong in any one area, and they understand that families demand that kind of breadth of instruction. Burke speaks regularly of engaging the head, heart, and hands equally. “That is certainly a lived philosophy at our school,” says Banack, “so there’s an emotional attachment, an intellectual attachment, and a physiological aspect through the physical motion of doing something. It makes learning much more profound.”

“Certainly there’s no single pedagogy that you can use in all areas,” says Banack, though he’s careful to offer an important caveat. “To suggest that our classes are only ever inquiry based would be inaccurate … but we believe that kids learn best when they do stuff. And that’s why we have all these Classroom Without Walls programs, and science labs and design labs, where kids get their hands dirty, and they build things.”

The faculty largely leads from behind, providing mentorship, direction, and support. They allow the students to drive their learning as much as possible within the context and the demands of the curriculum. Says Banack “The idea is that kids are able to collaborate around any kind of content [when] you teach them the skill of collaboration: how do you listen, how do you voice an opinion of dissention, how do you share that without bringing a bunch of emotion into things.”

The school works diligently to ensure that all learning is relevant, and that students themselves are always aware of its relevance to their personal aspirations and their lives outside of the school. “Once our kids have knowledge and skills, we want them to do something with that,” says Donaldson. “Action is an important part. We’re really an outward-looking curriculum, looking beyond our school to the communities.” That’s a function of the IB, and one of the reasons why the IB was seen as a good fit for the programs that existed here prior to adoption.

There is a greater amount of international experience at Meadowridge than you’d expect for a day school—faculty and students represent more than 30 countries —and that’s partially a function of the IB in consort with the school’s overall mission. Teachers are given dispensation to work overseas and experience the IB in other settings. Alan Graveson, post-secondary counsellor, was hired in 1991 and has since taught in London, England; Brisbane, Australia; and Shanghai, China. Another teacher has experience teaching at international schools in Romania and Kuwait. Banack has taught in Turkey, the Philippines, and Venezuela. Willms arrived after having taught in an IB school in Thailand. Where some schools might have disparaged overseas experience, Meadowridge is different. “Applying here,” says Willms, “Terry Donaldson was just celebrating that I was coming from an international school, which was great, because the two years I spent in Thailand was some of the best professional development I’ve had.” Hiring has been conducted not necessarily to augment international perspectives, but to add to a diversity of approach with a preference for candidates who bring substantive experience with the IB curriculum.

The International Baccalaureate

The International Baccalaureate (IB) was founded in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1968. Given the spirit of the time, coupled with an exponential growth in air traffic, there was a budding awareness that students would increasingly live in a multinational, multicultural world, with professional and personal lives that existed across borders and cultural boundaries. Likewise, it was surmised that communities of interest would develop independent of the local communities that students lived within—the community of physicists, for example, would be a global one, rather than associated with specific local institutional communities.

It was out of that ethos that the IB was born. It would offer a diploma that was as mobile as the students who would earn it, and it would be recognized readily by universities around the world. While rigour was important—students with the IB could be counted on to have a strong basis in language, math, and science—so was the kind of learner that the IB could develop. In addition to the core curriculum, students would be required to gain a meaningful sense of global issues, economy, geography, and culture. They would be required to learn the fundamentals of communication, creative problem solving, ethical leadership, and international politics. They would work and think across disciplines, applying math concepts to social economies, and science concepts to, say, community development. As such, the IB was, in a sense, at the leading edge of the development of what we now think of as 21st-century literacies.

Not all schools adopt the IB for the same reasons. For some, the attraction is to an internationally recognized curriculum, or university recognition. Those things are important attributes, though the draw for Meadowridge was how well the academic profile overlapped with what was already happening within the program: transdisciplinary, inquiry-based, value-driven, experiential learning centred on play in the primary and middle grades. As such, the transition to an IB Continuum World School was seen as an absolutely natural one to the degree that it supported and augmented the founding mission. Meadowridge earned its accreditation for the IB Primary Years Program (PYP) and the Middle Years Program (MYP) in 2007. With the addition of the Diploma Program in 2012, it became one of the first schools in the region to offer the full continuum. To date, there are only eight schools in British Columbia with the full continuum offering, making the IB a draw for many of the families that enrol at Meadowridge.

“The Learner Profile encapsulates those characteristics that we want to develop in order to prepare our children for an uncertain global future.”

Experiential and outdoor education

“The three Es are for Experiential, Ecological Education,” says James Willms, the outdoor experiential ecological education (OE3) coordinator. Meeting him, it’s clear why Willms was chosen to lead the program—he’s the embodiment of what OE3 was designed to promote: equal parts active living, stewardship, and creative engagement with the curriculum. The day we visited, he was preparing to take the Grade 3 students out for a mindfulness program based on the Japanese concept of shinrin-yoku, which roughly translates as “forest bathing.” “I reflect on my childhood, and I had a lot of time outside, and that was my freedom,” says Willms. “I just loved to roam, and I was afforded that. And so now we’re trying to create opportunities where we can afford that to our students, to allow them to be free and explore.”

In the early grades, the first part of the year is devoted to simply getting to know the forest, getting to know the space. Students go out into the environment at least twice a week, and it can be as simple as exploring sit spots: finding their space in the forest where they can just sit, reflect, and be calm. “It’s amazing to see. There is a range of kids who are really comfortable outside, and there are others that still don’t want to venture off the trail. It’s beautiful to see the challenge by choice,” Willms says. There is a range of learning promoted within the various activities. Hiding games within the forested areas of the property build confidence, though they also offer some very pointed experiences, as Willms notes. “It’s those moments in hiding when a child feels that anticipation, but then they’re getting smells from the earth beneath.” Back in the classrooms, the students don’t reflect on who won the game so much as they debrief the sensory experiences they had while they were involved within it.

Willms admits that a more typical approach to outdoor education—and the one that families perhaps think of first—is adventure, and there are certainly aspects of that included at all levels of instruction at Meadowridge. All children, even the very youngest, have at least one substantive outdoor adventure experience each term. In Grade 3, they start taking overnight trips, including one to Timberline Ranch in Maple Ridge; in Grade 4, they go to Sasamat Lake within Belcarra Regional Park in Port Moody; in Grade 5, students spend two nights at Camp Jubilee, which is up the Indian Arm. A capstone trip in Grade 10 is a five-day, four-night canoe trip, paddling up the Indian Arm in voyageur canoes. All the trips build students’ outdoor skills, and the program is designed to develop abilities and comfort levels incrementally over the years that they attend the school.

Still, the intention is to deliver more than just adventure, including an introduction to both the natural and cultural heritage of the region. In May 2018, the Grade 8 class went out to Qualicum Bay to do some caving and connect with the Qualicum First Nation. “They had a traditional salmon bake; some elders came down and shared stories with the kids,” says Willms. “I felt it was as authentic as a meeting with First Peoples could possibly be.”

He raises the example in order to give a sense of what he feels outdoor education really needs to accomplish. Caving, yes, but also social development. Outdoor activity, yes, but also curricular development. Curriculum integration is what Willms is particularly tasked to do: connecting with teachers and collaborating with them to develop unique learning experiences. “There’s so many things coming at our students, like climate change, clean water, food scarcity, and all these issues that are intimately tied to the natural world that we all share and depend upon,” he explains. However, faculty were finding that, while students were being asked to care for those issues and challenges, they were doing it because they were told it was important, not out of an intrinsic sense of care.

At Meadowridge, there are ample age-appropriate, curriculum-driven opportunities for students to build a meaningful relationship with what they’re being asked to care for. “Instead of having that siloed time—‘okay, we’re going to have outdoor time now, and then we’re going to do math and science’—we’re going to do math and science outside.” This way, students get exploration and experience while meeting curricular outcomes.

For early learners, that could be walking through trails looking for patterns. “Salmonberry bush leaves grow in threes, so they see that this is one of the patterns that can be used to identify the bush,” Willms explains. Back in the classroom, they may be asked to landmark where they saw the various patterns and to think about the larger patterns that they reflect. In turn, they engage meaningfully with mapping skills and learn the names of local species and habitat. The tasks grow with the students, leading to surveying, stewardship projects, and using trigonometry to measure the heights of trees in the high-school grades. Adds Willms, “It’s meeting the outdoor experience without adding anything new. It’s just changing the venue.”

Donaldson felt that, of all the spaces on the campus, the North Forest is most symbolic of the school’s culture. “It’s representative of what we believe is important and where we want to go.” That’s reflected in the development of the area itself. It includes a campground and a fire circle. The day we visited, the Kindergarten kids and their Grade 12 buddies (affectionately called Kinderbuddies) met there to have hot chocolate; the space was being used actively even prior to formal completion. The space needed some picnic tables, but instead of purchasing them, Willms collaborated with the Grade 10 math teacher for the class to design and construct some, with lumber donated by a family. “We’ll meet the measurement and some of the trigonometry curriculum requirements, the outcomes that he needs. [And] we get tables for the campground, and kids get to have tools in their hands. So it’s interdisciplinary.”

It’s hard not to be moved by that kind of thing. It’s also telling that Willms and others, while somewhat proud of the programs, don’t see them as remarkable necessarily. Rather, they are seen as reflective of what the school has done and what it wants to offer the students. Teachers across the disciplines are demonstrably on board. A Grade 12 student who has been at the school since Junior Kindergarten explains: “in the younger grades, if it’s a nice day, it’s up to the teachers if they want to do a class outside, if they can make that work. But it did happen quite a lot.” Says another: “when I was in Grade 3, we had a little garden, and we’d go out and dig in the flower beds and plant.” Another told us how they built trebuchets and launched metal balls, which was a high point, perhaps understandably. “We built castles out of popsicle sticks in the previous unit, so we destroyed those.” Fun.

Learning beyond the classroom

The Classroom Without Walls (CWOW) program is a touchstone of Meadowridge’s overall school culture and its dedication to experiential learning. It was developed in part to give more structure and substance to field trips, and to bring more relevance to the curriculum.

CWOW events happen once a month, and they are an opportunity for instructors to plan unique activities, projects, labs, and explorations. For example, the investigation around why salmon weren’t returning to Latimer Creek (the creek that abuts the campus) was handled largely through CWOW programming. A full day was scheduled for the investigation, which was informed by a short documentary and a visit to a local fish hatchery. Students learned what to look for to determine the health of a stream, and then applied that learning to their investigation of the creek. On campus, they did water testing and surveyed the various problems associated with the waterway, including the accumulation of garbage around a culvert, lower water levels, and a steep drop, all of which were the result of road development.

Week Without Walls

The Week Without Walls (WWOW) is a related program that has many of the same goals. There are two of them, one in September and one at the end of May. The September week is focused on outdoor recreation, providing an opportunity for students to bond and build relationships to start the year. All trips feed off the energy of shared effort. The students also learn about the local geography, ecology, and natural and social history.

Athletics

Meadowridge competes at the elementary level in School District 42, a group of 28 schools (a majority of which belong to public boards). The school also competes in the Independent Schools Elementary Athletics Association (ISEA), which includes schools throughout the lower mainland. In the upper grades, they compete in the Greater Vancouver Independent Schools Athletic Association (GVISAA), which includes more than 33 schools (all smaller independent schools in the Lower Mainland). As a result, there’s a sizable competitive community.

Volleyball, soccer, basketball, cross-country, swimming, and track and field are the school’s foci, though there’s a flexibility to the programming from year to year. The fencing program is in its tenth year, and was adopted because of the availability of coaching: there’s a coach who placed fourth in the Olympics and who was a champion in Europe. The school also hosts a fencing tournament each spring. Other sports are added for what they can bring to the student experience. “I like soccer because it’s not about the best players,” says Spurgeon, “it’s about the best team.”

Spurgeon has directed the athletics program for 15 years. He’s affable and approachable, and he has a good sense of what he wants out of the program and how it relates to the overall student experience. He explains that “we want kids to be broad learners, and not just academically strong, but also physically and mentally strong.” His intention is to bring forward all the things that athletics teaches—“hard work, challenging yourself, how to deal with losses and wins graciously”—rather than totting up wins. He adds that the Meadowridge athletics program aims to foster healthy habits in students for their entire lives. “I want them to do something like this after they graduate, so that Grade 12 isn’t the end of their athletic career. … maybe they get into fitness and they decide to go to run a marathon.”

The fitness room has free weights, machines, balance pads, mats for yoga, and body weight resistance. One trainer, a kinesiologist, does sessions in the mornings for the school’s teams and staff. More than 45 members of the staff are involved with coaching, something that speaks to the place that physical activity has within the culture of the school. The hope, says Spurgeon, is that students will gain “a confidence in themselves that, athletically, they can do something, and a knowledge of how that effort transfers over into other aspects of their lives … the understanding that they can get through difficult times by working hard, having a plan, and working together with the people around them.”

“The first thing I did when I arrived here is I changed all the playgrounds. Made them biodiverse, with a hill in the middle, paths so the kids can run through the woods. We think that the connection to the natural world is critical.”

—Hugh Burke

Athletic instruction begins with Grade 3 cross-country, then swimming and fencing in Grade 4. It continues from there, with ample opportunity for students to participate in a growing range of activities. Spurgeon is careful to not have too many crossover sports—those with overlapping skill sets—and he’s also developed the program to ensure that anything a student starts in Grade 5 can be continued through Grade 12.

Until fairly recently, the school maintained a no-cut policy. However, growth in the programs, as well as the school itself, has made that policy more difficult to maintain. Nevertheless, the underlying intention remains. Until the Grade 8 level, students are guaranteed playing time in all athletic programs they wish to participate in. From Grade 8 up, all students are encouraged to join a team. During tough games, coaching tends to be a bit more mercenary, although coaches otherwise work in the hopes of circulating through all members of the team. When we visited, Spurgeon was juggling getting ready to take the soccer team to a major tournament, embarking on a Costco trip, and packing the bus for the journey. He says that the effort is worth it: “We’ve had the most success in boys’ soccer. This is our fourth trip to [the] provincials in the last seven or eight years. Last year, we were third in the province.”

Student population

Students present as bright, positive, eager, and happy. While some arrive on foot or by car, many of the students arrive by bus, though the routes are local. While there are outliers, the typical student commute is under 40 kilometres. “I don’t live too close to the school, and there was a public school right next to my house,” one student told us of a momentary sojourn at another institution. “They have the IB program there as well, and I needed to organize my [athletic] training outside of school, so I thought we could just make that work.” It didn’t. “I realized that Meadowridge has a totally different level of education relative to public schools. And I really missed everyone here.” The students we met were of that ilk: prone to be proactive, and engaged with the academic and cultural aspects of the school.

Many students arrive in the earlier grades and continue on, so they wouldn’t have been as actively involved in the school choice decision as older students tend to be. “I didn’t want to come,” admitted a girl who arrived in Grade 6. “It’s an IB school so I thought the homework load was going to be pretty heavy. But then after coming, it’s actually not that bad, even in Grade 10.” The feeling is that challenges are real but attainable within the context they are offered.

Students gather in several common areas, of which the cafeteria is a prime location. A majority of the grades gather there, and faculty gather there as well. The atrium is similar to the cafeteria, in that it’s a large open space where students and faculty tend to gather, particularly those in Grades 8, 9, and 10. The hierarchies are flattened, something that those common spaces demonstrate. “They don’t look down at us,” one student told us of the teachers. “We’re all the same. I consider them as friends. It’s relaxed and friendly. I can tell them what I want to say.”

“We talk about being for others because it is really important, in an increasingly selfish world, that one can act unselfishly. And we talk about being in a just community because the way that we treat people, the fairness that we bring to things, creates the world around us. So what do we do well? We teach children to live well with others and for others in a just community.”

—Hugh Burke

Pastoral care

Teachers greet the students at the front of the school as they get off the buses, and the program of pastoral care begins at the front door as well. Each day begins with an understanding that, in Burke’s words, “everyone here is noticed and is important.” Care is rightly seen as the job of everyone, something the teachers clearly take to heart. Daily physical activity is required throughout the grades.

There’s a clear and keen attention to the development of wellness programs, both formally and informally, wherever and whenever opportunities present themselves. For example, Willms noted that the forest bathing exercises “stemmed out of the first Grade 3 inquiry unit … we’re certainly finding, just in general, [that] child anxiety just goes up, up, up—and it’s providing students with the skills to be able to regulate and decompress, to calm.” His voice rises a bit when he speaks about these things, and it should. He and others throughout the school share a dedication to wellness as a daily provision, not relegated to specific units of inquiry or dedicated counselling roles.

“There’s a level of engagement,” says Banack, “where everybody at the school has a different role, but the goal is the same.” There’s ample evidence of that, both in curricular and extracurricular spheres. Says Bereza: “many kids—when they’re solely focused on university, burying their heads in the books—they never learn mindfulness, they don’t learn healthy ways to deal with anxiety, they’re sleep deprived. And, yes, they get in to university, but when you look at the dropout rates at university, they’re unbelievably high because many kids aren’t able to handle the stresses of life as distinct from the stresses of academics.” The attention to those stresses, and preparing students to meet them, is significant.

Each academic year begins with a Welcome Back Fair in order to get everything started on the right note. “It’s really a drawing together of community,” says Bereza. “We’ve opened it up to the larger Maple Ridge community as well. There’s games for the younger kids—bouncy castles and those kinds of things—and our older kids are running those stations. The parents are involved. One year we had a food aisle where parents showcased the foods of their cultures. It’s just a chance for people to be themselves with each other, apart from being in a classroom. It’s a great way to start the year.” It’s an important event in the school calendar and it’s unique in the world of private schooling, showcasing many of the values and the communities that inform the delivery of the programs. While many schools have large community events—the Winter Bazaar at Crofton House, for example—they typically celebrate holidays. The fair at Meadowridge is intended to be more inward looking, celebrating the community that the school sits within. It’s lovely in every way, and it’s an excellent introduction to the school culture.

Within the day-to-day, there’s notable latitude for faculty to comport themselves in the ways that they feel best express their goals, values, and aspirations for the students. Bereza, while principal of the High School, continues to teach a course, something that she’s aware is highly unusual for administrators in similar roles at other institutions. “I still teach a class because I’m passionate about teaching … I believe that, in my role, I need to stay connected with the kids, and that changes everything when they can see me in a different manner than just the person they come to when they get in trouble. For me, it’s those hellos in the hallway, having lunch with the kids … it puts a smile on my face every time.” Nice.

Those kinds of informal structures contribute to and augment the more formalized care programs. The student advisory program begins in Grade 6, with each student assigned to a member of the faculty who provides academic counselling and works with the student to develop daily routines and study skills. Whenever students encounter difficulty, the advisor will reach out to parents, and potentially other faculty and staff. Advisors also work with students through any social issues that arise, monitoring mental health and engagement in the overall life of the school, and developing independence and executive function: organization, planning, and time management. By all indications, advisors and counsellors make themselves available. One student told us that “you can send them an email or book an appointment literally any time.”

Post-secondary planning

There are three post-secondary counsellors on staff, and academic counselling begins in earnest in Grade 9. In addition to the expected interest inventories, the counselling team organizes events, including career round tables for students in Grades 9 and 10 to hear from people who are further along in their careers. Graveson says that these events help students “to see what that progression and development looks like. … We bring in a lot of alumni to do sessions with the students, so they can hear about what it’s really like to study engineering right now, and those kinds of things. And that helps complement the diagnostic assessments.”

There is an easy interface between the counselling offices and the student body. Brianna Just, one of the post-secondary counsellors, notes that “especially in a small school like this, we get to know the kids really well.” Counsellors are dedicated to specific students, working from Grade 10 through Grade 12. “We get to see them develop and watch that discovery happen, in terms of starting to narrow down what they’re interested in, and to begin to see how that’s going to fit into their plans.”

Getting in

The admissions process is, for the most part, what you’d expect of any private school of similar profile. An admissions interview is required for all grades, with the SSAT required for Grades 6 through 12. Entrance at Grade 12 is very limited as it is the second year of the two-year IB program. That said, the admissions team is clearly not interested in rushing potential students through the process, but rather is keen to take the necessary time to make sure the fit is right for all parties. The interview is more a meeting than a test. To prepare for it, “Don’t worry about trying to drill your kids on literacy and numeracy skills,” says Donaldson, “but put them in situations in which they develop all those social and emotional skills, because that’s what’s going to make them a good candidate for our school.”

Donaldson contrasts the school’s admissions process with the one he experienced as a student entering university. “[The] universities had no idea who I was as a person” but looked only at marks. “Now they’re looking at people’s commitment to volunteerism, to community involvement. … Marks are important, but so are all those other things.” He notes this is true at Meadowridge as well: students are assessed on who they are as people, and the admissions team works to bring that to the fore. Further, a family interview is booked for all applicants from Junior Kindergarten through Grade 12, which families are right to see more as an opportunity than an obligation.

A tour of the school and the grounds is recommended, and it’s best conducted while classes are in session. Attendance at school community events can also serve as a valuable introduction.

Money matters

Tuition and fees are commensurate with similar programs elsewhere. Incidental fees are perhaps a bit lower, but as at any school, they are discretionary and largely a function of student involvement and interest. They include fees for field trips, yearbooks, textbook rental, mandatory supplies, workbooks, and graduation fees. The parents we spoke with noted that there were no surprises throughout their time with the school, and that fees, both recurring and incidental, were accurately and efficiently communicated in a timely manner.

There are costs associated with admissions, including a deposit levied for annual re-registration. There is also a one-time deposit, the Meadowridge Education Investment Deposit (MEID), payable on admission and redeemable when the student leaves the school, which many families end up donating back to the school.

Currently there is no financial aid at enrollment, which perhaps is atypical for a school of this size and focus, though the administration clearly intends to develop an aid program. In the meantime, families have payment options, including monthly installments, to allow them to manage fees over the course of the full calendar year.

Parents and alumni

Parents are welcome and visible in the life of the school on any given day. Opportunities for involvement range from shelving books, to participating in events, to membership within the board of governors. When we visited, there were two parents in the library, checking books back in and helping out around the front desk. There is a large school/community garden, including 18 raised garden boxes and a working greenhouse. Parents come in to help out there, cleaning tools and organizing the sheds.

Parents are given a chance to socialize outside of the school setting during evening Parent Socials hosted by the head of school at his home

There and elsewhere in the school, there’s clearly a desire to innovate, and that’s true in parental involvement as well. Once the campground is complete, says Willms, “we’re going to be offering overnights with families. We’ll host it, provide the tents, organize the food, and just talk about camping,” this is for families that might be new to camping or new to the country. “It’s been a long road to get to where we are, but it’s starting to become part of the ethos of the school.” It’s hard not to be moved by these kinds of initiatives.

The takeaway

If you were to create a school from scratch, what would it include? What would you borrow from the past? What would you innovate? Where would you put the school, and what would it sit next to? As attractive as it might be to be located in the heart of a city, you’d know that there’s value in having room to grow and having access to a variety of outdoor learning spaces. You’d want trees to measure, animals to ogle, and leaves to name. You’d keep some private school traditions—houses, for example—while updating others. There would be uniforms, but there’d be options beyond just kilts and ties.

In the classrooms, there would be more tables than desks. You’d want opportunities to build resilience and teamwork, and you’d create spaces with those lessons in mind—just as much as you would develop quiet places to read and think big thoughts. You’d build something that was sympathetic to the environment and sympathetic to growth. You’d build in opportunities to review and the capacity to change. You’d want to be responsive to the people in the building and what they need, knowing that as people grow, some of their needs might change, too.

And that’s precisely what Meadowridge is. It’s literally a product of that kind of questioning, and the result is a school firmly rooted in its time and place. It’s a conscious reflection of the social, cultural, and natural contexts it sits within.

While all schools are unique, Meadowridge nevertheless proves the point. It’s an IB school, though it adopted that curriculum out of an understanding that the IB was an opportunity to formalize the values and the programs it was already offering, rather than adopting the IB and then aspiring to fulfill it. Meadowridge has rightly put its own character on the delivery of the IB, augmenting it in meaningful, creative ways.

And while parents look to schools to offer strong academics, and perhaps strong athletics programs, the best schools are notable for the health of the community that they encourage. Meadowridge is a prime example of that—the students and faculty clearly feel that they are part of something larger, and that they are participating within the life of the school as well as the life of the communities and families that compose it. It’s a vibrant, unique place. While Meadowridge may not be the most famous private school in Canada, it has a very large profile within private education, and schools rightly look to it as an example of how they might develop their programs.

“We don’t see children as needing correction, we see them as needing care, nurturance, guidance, support, and warmth. We want our children to live well. We have children live well so that they learn to live well. We have them work with others so that they can learn to be social beings, and get along with others, in a complex world.”