Upper Canada College THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Upper Canada College, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Our Kids editor speaks about Upper Canada College

Introduction

It’s safe to say that, whatever expectations you might have of Upper Canada College (UCC), a visit to the school will disrupt them. To be sure, people generally arrive with a lot of preconceptions; even those with no experience of the school have lots of assumptions about it, because its profile is so high. It’s the most storied and known institution of its kind in Canada, sitting (in the popular imagination, if not in reality) at the business end of the academic world: competitive, serious and stern, old and monolithic, traditional and unmoving. Julia Kinnear, academic dean, admits that “we probably have a perception out there of being, I don’t know, cold, maybe a little stuffy.”

UCC may have been those things at some point in its history—and, yes, it’s old and has many traditions—but the surprises begin pretty much from the parking lot. You arrive with a sense that this is the kind of place where it would be very easy to park in the wrong spot and risk getting towed. You just assume that there must be a lot of rules here, given what it is, where it is, and where it’s been. So, when a security guard started crossing the lot toward us, the thought was, well, here we go. In fact, he wasn’t interested in us in the least. A smile, a wave. That was it. No corrections. While the buildings are all accessed through security passes (that’s typical of any school), the campus is welcoming to visitors, open to local foot traffic, and lovely in the degree you’re able to set aside thoughts of grandeur—which isn’t as easy as it sounds, given the outward gestalt of the place. But you should, nonetheless. It’s just a school, after all—a really, really good one.

The entry to the Upper School is impressive, to be sure, and sits beneath the clock tower that dominates the campus. Inside is a lot of marble and glass, and there’s a sizeable bronze crest inlaid in the floor. No one steps on the crest, the belief being that it’s bad luck. As we stood there on the crest (we only heard about the curse after the fact), wondering where to put our hands, a man approached, welcomed us, and stood and spoke for 20 minutes before asking why we were visiting. It was Sam McKinney, the principal. The meeting was as charming as it was unexpected, and the experience just grew from there.

“It is about supporting students and guiding their journeys toward their best selves...”—Sam McKinney, Principal

The faculty and staff are, frankly, notable in all kinds of ways, including amiability. Many have taught in international schools around the globe and have an armful of degrees. Jeff Aitken, head of the Upper School has extensive international experience, including leadership roles in several International Baccalaureate (IB) schools. Sarah Fleming, Head of the Preparatory School, began her teaching career at American School Foundation of Monterrey, in Monterrey, Mexico and joined UCC from the International School Bangkok (ISB), where she was Vice Principal of the Elementary School. Originally from Ottawa, she has spent the past 15 years overseas in a variety of teaching and leadership roles.

Both Aitken and Fleming are heavy hitters in the company of a lot of heavy hitters, and within a faculty that is rife in international experience.

That said, there’s a nice mix between business and fun. Despite the school’s lofty reputation, there is a concerted effort to buoy the weight of history and to create reminders that, after all, this is a place for children to learn and grow.

The philosophy of the department of student life and well-being is to guide students to understand who they are, what role they might be able to play in different situations, and the positive impact they can make to make things different. UCC helps to guide students in their journeys toward becoming the best version of who they can be in their world. Every student will experience the world in different ways, but UCC wants to ensure every student knows they can make a positive contribution. “We like to be humble,” says Gareth Evans, assistant head of the middle division of the Prep School, at the risk of undercutting his message. True, it’s hard to be modest in such an august setting, but it’s telling that they try. That said, it’s also right that they don’t hide their light under a bushel. Evans adds: “We provide transformational learning experiences that foster the development of head, heart and humanity and inspire each boy to make a lasting and positive impact on his world.”

Key words for Upper Canada College: Tradition. Community. Challenge.

Basics

The school is located, quite literally, in the middle of Avenue Road (a major north-south artery in Toronto), with traffic diverting around it. The property, known when the school located here in 1891—as it is now—as Deer Park, was purchased before Toronto had extended that far north. Then, this was countryside; today, it’s the heart of one of the toniest and most desirable neighbourhoods of the city. The grounds are expansive—the property is 35 acres—in a manner that would be impossible to create here today, and they include an impressive amount of green space. The beltline trail runs just to the north of the campus, and both it and the campus create an idyllic feel despite the urban density. UCC is a Toronto landmark, and it’s one of the most visible—and visibly arresting—schools in the city.

The program follows the IB curriculum, and runs from SK to Grade 12. UCC also refers to years instead of grades, so the program runs from SK to Year 12, divided between the Primary Years Programme (SK through Year 5), Middle Years Programme (Years 6 to 10), and Diploma Programme (Years 11 and 12). The SK to Year 7 classes are housed within the Prep School, which sits at the southern boundary of the property. The Upper School (Years 8 to 12) is centered around the Massey Quad, the visual focal point of the campus and the area that is most frequently shown in photographs. The clock tower dominates, prominently visible from Avenue Road—the tower really calls out the school and is perhaps responsible for why so many people know that it’s here in their midst. It was completed in 1960 to replace one that had existed here since UCC moved to the site.

The Upper School isn’t as old as it looks (the one in the archival photos is similar but was removed), though it was designed to reflect the traditions of the school and the buildings that had occupied the site prior. The funds to build the tower were provided by the Rogers family headed by Ted Rogers, an Old Boy and founder of Rogers Communications. The building that it sits above was dedicated by Governor General Vincent Massey at a moment when the school was rising to a regained prominence in the life of Toronto and, in a sense, the country.

While small in proportion to the overall student population—there are only 88 boarding spots, divided equally between two houses that sit on the quad—the boarding experience nevertheless has a unique place within the culture of the school. “It’s like living with a lot of brothers,” says a boarder in his first year of the boarding program. When the weather’s nice, you’ll likely find some students taking a breather, as we did, in Muskoka chairs just near the statue of the founder, Sir John Colborne.

School leadership

UCC has two heads—one for the Prep School and another for the Upper School—instead of dedicated heads of different grade level divisions within the school. UCC principal since 2016, McKinney was raised in St. Catharines, Ontario. His first teaching job was in the public system in Guelph. He then took a job at a private school in Australia, and there became a proponent not only of things that independent schooling can do, but also a champion of the International Baccalaureate. Twenty years later, he found himself at the head of UCC—a job that he admits is not one that he, as a young person, would have imagined moving into or perhaps even been aware of.

“this is a human profession, and I believe that’s what education is … relationships matter to me most” —Sam McKinney, Principal

In some schools, the principal or headmaster remains somewhere apart from the student body. In others, they are known to the students and seen somewhat regularly. McKinney is the next best case: he’s known to everyone, is approachable to everyone, and indeed approaches everyone. Some might say that’s not so important, given that the job of the administration of the school is to, well, administer the school. But McKinney sees his role in larger terms, including setting the tone for the ongoing culture of the institution. “Usually you think of the principal as a really high figure in the school,” says a student in the boarding program, giddy at the story he’s about to tell. “But one day last year, he just comes into the math room and says, ‘who wants to arm wrestle?’ And so everybody lines up. And he beats everybody.” Apparently McKinney’s a skilled arm wrestler, so he wasn’t graciously setting himself up for failure, as much as the boys might have thought (or hoped) he was. In any case, the boys loved it, and it’s a story that they are prone to repeating for no other reason than for the joy of it.

His interaction with us, with the staff, and with the students in the hallways made it plain that McKinney sees his role as one of providing, among other things, a model for others to follow. He behaves this way—approachable, friendly, active—because that’s the face and the personality that he’d like to see expressed by the school. He says, “this is a human profession, and I believe that’s what education is … relationships matter to me most,” including those with students, parents, alumni, and colleagues. “I can send emails, or sit behind a closed door, but that won’t give people the confidence and trust that needs to exist for us to be able to achieve what we need to achieve as a school.”

He speaks of the school’s future more than the past, talking less about the school that he inherited, and more about the school that he and others are working to develop. Community and relationships feature highly within that. “What do [the students] take from the school? They take relationships, and they talk a lot about brotherhood, but it’s really about connection—both to each other and to the College itself, including its culture and traditions.” Parents confirm that focus, to be sure. One told us that, “at the end of the weekly assembly … , they all have their arms around each other and are swaying back and forth as they sing the song ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone.’ [My son] didn’t have that when he was in public school” before moving to UCC. “It’s a tradition that’s memorable for them,” she adds, her voice breaking as she does. An alumnus commented on the sheer, unbridled energy when the song is sung. “No boy in the hall holds anything back. And the singing builds to a crescendo, peaking on ‘NE-VER’ in the final stanza.”

While he may not express it in exactly these terms, McKinney sees the strength of the UCC program as a product of its ability to provide a challenging, socially aware community for the boys to participate actively within, both on campus and beyond. One of the first visible projects that he instigated on arrival was one based on truth and reconciliation with the Indigenous communities, and it is telling of his approach. It culminated in a permanent art installation in the student centre. He says that “we have a responsibility to help the students, while they’re here, develop a sense of personal responsibility to make a positive difference in their lives beyond the school.” That includes a responsibility to not shirk from the challenges of history, as well as the challenges we face today.

For him, that means giving students real opportunities to explore; to engage in a rich and robust academic program; to challenge themselves on a stage with a musical instrument, or on a playing field; and to find out things about themselves that they may not know. And, last but not least: “To find out things about their friends that they might not have expected. And to discover [those things] while they’re here.”

Parents confirm our first impressions of the leadership team, one commenting on “how approachable the members of the leadership team are, and how well they communicate both positive and negative issues … In my personal experience, feedback was immediately addressed, in an appropriate manner.”

Background

The school was founded by Sir John Colborne, and his statue—staid, streaked with copper-green—dominates the quad. He was, in every way, a product of his time, namely the age of empire. He served in wars, led troops, and sought to provide British leadership in the new world. In 1828, he was appointed the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, and the following year—as one of the very first things he did in his new role—he founded the College. He didn’t stay long, though of course that was his intention. He wasn’t interested in running a school, but rather in creating a non-denominational institution that would supply the colonies with leaders, educators, and merchants. The College’s board and leadership are considering Colborne’s legacy in dialogue with students and alumni as part of the school’s commitment to pluralism.

UCC, as with King’s College (which was founded just the year before), was created to help maintain the realm. Leaders, and perhaps Colborne in particular, knew that they needed to build a local administration in order to keep young men from travelling abroad to receive an education, allowing them to stay to administer and defend the colonies. In his Throne Speech to Parliament in 1829, Colborne said, in the delightfully convoluted manner of his time, that “unceasing exertion should be made to attract able Masters to this Country, where the population bears no proportion to the number of offices and employments that must necessarily be held by men of education and acquirements, disposed to support the laws and your free institutions.” Upper Canada College was established by an order of the provincial government, and Colborne hired faculty from the UK to teach there, attracting them with the kind of salaries needed to lure them across the Atlantic. It was a bastion of English cultural life—Charles Dickens praised it, and dignitaries visited it—and the school carried on in that vein, as a cornerstone of the cultural life of the colony it was named after.

There was a strong association with the military; boys were expected to be prepared for deployment at any time, as occasionally they were. During the Fenian Raids of 1866, UCC students were mobilized to guard military buildings and the port in Toronto. That said, the expression of military ideals wasn’t formalized until the creation of the Cadet Corps of Upper Canada College in 1869. Through its 127-year history, those military ideals remained an integral part of school life. Students took part in regular drills and exercises, sometimes with active rounds.

The cadet program was developed as an expression of the spirit of volunteerism and the militia movement, and it maintained an ongoing association with the national military. In time, however, it began to feel less relevant—more a relic of an earlier time—especially when real rifles were replaced with wooden ones, or when real training evolved into a pantomime of military experience. Still, it held on longer than you might expect. At UCC, the corps was formally retired in 1987, one of the last of its kind in Canada.

“Private school with a public purpose”

Colborne wanted the school to produce the human resources required to build a nation, and, from the opening bell, that’s precisely what it did. Where some schools of the time addressed the needs of specific communities—Ridley College to the south as an Anglican school, Pickering College to the east as a Quaker one—Colborne wanted a school that would address a more overtly public purpose. Being non-denominational was evidence of that—it was unusual for the time, though it signified a greater, more public purpose. Colborne may have thought of public service differently than we do today, though an attention to the world beyond the school has consistently been a guiding principle of the programs. In 2002, then principal Douglas Blakey restated that commitment during a speech to the Empire Club of Canada. “I think there should be an always-present question never far from the figurative surface,” said Blakey. “How best can the institution, not just its students and graduates, serve the greater public good?”

That commitment has been reaffirmed in the years since, particularly in the lead-up to the school’s 200th anniversary in 2029. It’s also expressed as one of the three pillars of growth at UCC: “embracing a culture of courage, striving for excellence, and advancing the common good.” If there is one thread that has remained through the two moves, the growth, the change, and the years, that desire to look to the common good is it.

“I think there should be an always-present question never far from the figurative surface...How best can the institution, not just its students and graduates, serve the greater public good?”

—Douglas Blakey, former principal

Academics

The program, for approximately the first century of the school’s life, was rooted in a classical education, providing a survey of knowledge with an eye to graduating students into the professions of medicine, theology, law, and military leadership. While there have been countless amendments to the program over the years, perhaps the largest period of change, in terms of the delivery of the curriculum, occurred in the 1960s—in keeping with changes in the wider social culture—with the school moving to a more modern conception of the liberal arts. For the first time, world languages were offered in addition to Latin, for example, though there were lots of subtle changes as well.

All of that provided the groundwork (though perhaps this is only clear in hindsight) for the adoption of the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IBDP) in 1996 and the Primary Years Programme (PYP) in 2003. The school received accreditation for the Middle Years Programme (MYP) in 2020, making UCC the only boys’ day and boarding school in North America to offer the full IB continuum.

In all, perhaps it hasn’t been the most intuitive adoption of the continuum—for 15 years, the PYP and the Diploma Programme bookended a more traditional middle school program. But as academic dean Julia Kinnear says, it made sense at the time—and in any case, there was a continuity to the school that was clear in practice, if not entirely on the face of it. Kinnear adds that the adoption of the MYP underscores an institutional commitment to that IB framework as being the one “that’s really best for us and aligned with what we want to offer across the school.” Her role, primarily, has been to make that happen. “For us, in terms of what our school mission has been, from 1829, that idea of a liberal education,” she says, “I firmly believe that the IB matches that.” She notes that it’s about classroom learning, but also all the other domains of learning, including co-curricular programs, service learning, and educating students to understand their place in the wider world. “Those values that are part of us, and have been a part of us historically, are really aligned with the ethos of the IB programme. It’s very complementary. I’m a big believer in what it brings us as a school, align[ing] where we’ve come from and our values.”

That includes an appreciation of the emphasis on inquiry, with students actively framing their own learning and considering the core concepts through the lens of the global context. One parent commented that the IB’s “strength is in teaching not only information but how to learn, how to ask questions, and what to do with that information.” Says Kinnear: “Interdisciplinary units of study are an exciting part of the MYP that we’re putting our own unique spin on. We’re developing project weeks when all students in a grade will have the opportunity to go off the regular timetable and deeply investigate one topic from the perspective of multiple subject areas. We’ve chosen the UN Sustainable Development Goals as the framing concept for these weeks as part of our commitment to exposing students to issues of global importance in the curriculum.”

“The reason I like the MYP, especially for our students, is that it teaches them ‘how to learn’ and helps them recognize and appreciate their own perspective and the perspective of others at a critical time in their developmental journey,” says Sarah Fleming, head of Prep school. “In our MYP design classes, students use the design cycle—researching, prototyping, testing and iterating—to develop solutions to problems they identify in the world around them. In the process, students develop empathy for the needs of others and learn that success takes time. They also practice the kind of flexible thinking they need to evaluate information critically and apply their knowledge in complex, unfamiliar situations.”

The development of the program in design thinking and digital innovation is an example of how UCC is striving to deliver what Kinnear prefers to call a “liberal education” over a “liberal-arts education,” which is admittedly a fairly fine line. “What that means for us is a notion of students having experiences that cross the disciplines—that idea of disciplinary breadth on the curricular side,” where what students are learning in the curricular realm is augmented through a rich and varied co-curricular offering.

The strengths of the IB, in Kinnear’s view, are many, including an emphasis on transferable skills, long-term projects, and cross-disciplinary studies. IB has a broader range of topics. Even if a student isn’t particularly interested in calculus, they really might be interested in financial math, or they really might be interested in some with vectors, for example. And they get exposure to all three things rather than being funnelled into a narrow field.

Assessments are detailed and frequent, says one parent, “and often include specific examples from their work or learning.” He notes that instructors provide regular updates, both in the weekly school communication and also through direct emails and online portfolios.

UCC awards both the Ontario Secondary School Diploma and the IB Diploma to graduates.

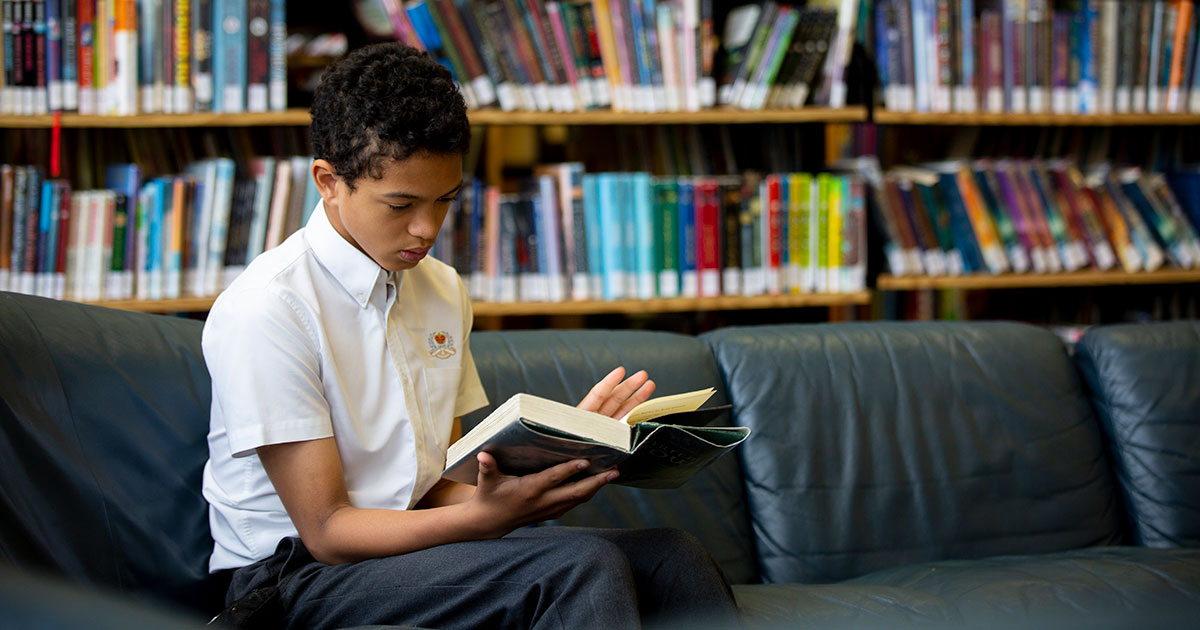

Richard Wernham & Julia West Centre for Learning

The Richard Wernham & Julia West Centre for Learning was established in 2001. Made possible through generous donations, it was developed around four key mandates, one of which is working with boys to offer programming and opportunities for them to understand what their own toolkit for learning is and what their strengths are, and to understand themselves as learners. Despite what the name might suggest, while there are dedicated spaces for the work of the Centre, they are integrated throughout the school rather than in a separate building or suite of offices. This is designed to create a broader interface between the students and support that is offered by the staff.

Says Kinnear: “The piece around leading practice for teachers, and the fact that the school encourages teachers to be engaged in research, that’s something that I find appealing and reassuring.” For students, it provides opportunities for learner awareness and growth, and better understanding of what their own style is and where their weaknesses might be. “I don’t underestimate the impact of that on a student and what that gives them in the way of confidence, owning their own learning and advocating for themselves. … It’s our attempt to really think boldly about the kinds of skill sets, capacities, and experiences that we want our students to have.”

“When the person sitting next to you wants to achieve,” says McKinney, “somehow that helps you want to achieve. …. There’s something that sweeps you along … and when achievement is fostered, and is celebrated in genuine ways, that’s when you see the best outcomes for the students in the school.”

He believes that one of the greatest things that a school can offer students is a sense of confidence in their abilities. To be sure, UCC seems to have no trouble at all in that regard. Someone with a more cynical outlook might suggest that UCC does that job perhaps a bit too well. When asked what he wants to be when he’s older, a student in Year 6 at the Prep School said, without a blink, “I want to be prime minister.”

Jeff Aitken, head of the Upper School, provides a good a snapshot of how these ambitions play out and how the school fosters them: “It means that he is aspirational, and we haven’t, through the process of education, squashed his aspiration. In fact, I hope we’ve encouraged it. It means that he’s concerned about civic responsibility. It means that he’s concerned about others. It means that he’s thinking about ways that he can give back to his community. Depending on the age of the boy, it could mean that he’s power hungry, but [given that he’s in Year 6] it’s not that.… I feel that it comes from a good place and that it’s idealistic, and I think in many ways we try to promote that idealism in our young people, to have hope for a better future and to also not feel that the status quo is okay, that no status quo is okay. It’s an attempt to always want to make things better for you, your family, your community, for those around you. And that’s something I hope we continue to encourage in our young people.” (The student’s own explanation for his aspiration was: “I’m very interested in politics, I like leadership, and I like helping people.”)

That’s a lot, and to be sure, that’s precisely the kind of approach that enrolling families are paying for. McKinney says that one of the jobs of the school is to grant students a confidence to work with what they’ve learned, and to gain a voice that they can take with them into leadership roles. And he’s right, of course. Their job, as educators, is to find the balance between encouragement and false confidence, aspiration and elbow grease. By all accounts, per the parents we spoke with, they’re fairly consistently hitting that mark.

“I’ve got to show you this,” says Shaan, turning to a wall in the hallway connecting the science labs. “These are amazing.” He’s a Year 11 student giving us a tour through the Upper School. What he stops to show us is a wall of science and math jokes. “I love these departments because they are so closely connected that they do extra stuff like this.” Some of the panels are jokes written in mathematical or chemical symbols. Others are more intelligible. One reads: ‘Think like a proton: always positive.’” “Yeah,” Shaan says, chuckling with a hint of self-consciousness. “Well, sometimes they do get a little old, I guess.”

“Everyone is good at something...and everyone has the ability to find something that they’re good at. It breeds a healthy competition where people are focused on being their best selves.”—Shaan, student

It would be easy to poke fun, of course. Laughing at a joke written in algebraic symbols is, to be fair, a bit parochial. Nevertheless, it underscores a culture of learning. Students also find, by and large, that they are learning in a community of people who share their talents and aspirations, even from a very young age. We sat in on a Year 3 classroom and asked what the boys felt that they had in common. “We’re all smart,” offered one, which, when you think of it, is a fairly astute thing to say. They are all smart, in fact, and all operating at the top of their peer groups. Having an outlet for their intelligence is welcome—and this seems to be true even for the younger students. Shaya, who toured us through the Prep School, says he wanted a challenge, and he admits that, here, he got it. Says another: “At times it was challenging, but I would never classify the work as too difficult. I have always been able to complete the work if I created a plan and executed that plan.” That’s something that the Centre for Learning provides resources for, though teachers do as well.

The students are highly aspirational—something that, within this context, doesn’t feel out of place. This is a school, after all, where Stephen Leacock, Robertson Davies, and Michael Ignatieff have all been editors of the yearbook. That culture of achievement is one of the reasons these boys are here—it’s a place where a student can say he wants to go to MIT in the knowledge that he’ll be taken seriously by peers and mentors who, for their part, have a realistic view of what achieving that goal actually requires. In an environment where anything is seen as possible, everything is possible.

There’s a healthy air of competition, though not relating necessarily to marks or overt academic achievement. UCC doesn’t address itself to geniuses so much as it addresses the program to students who are academically ambitious. “Everyone is good at something,” says Shaan, “and everyone has the ability to find something that they’re good at. It breeds a healthy competition where people are focused on being their best selves.”

Resources are plentiful, as are the opportunities for professional development. Says Evans: “if a teacher has a passion or an initiative that they want to run with—if it’s reasonable and connected to the curriculum—it’s going to be supported.”

Facilities

Many of the buildings are quite old, and some spaces show their age a bit, though never to a fault. They grant a sense of place. Of the 42 classrooms and labs at the Upper School, 29 have been renovated in the last five years, the most recent of which is the East Wing which houses science and language classrooms. UCC also has dedicated design labs in the Prep and Upper schools.

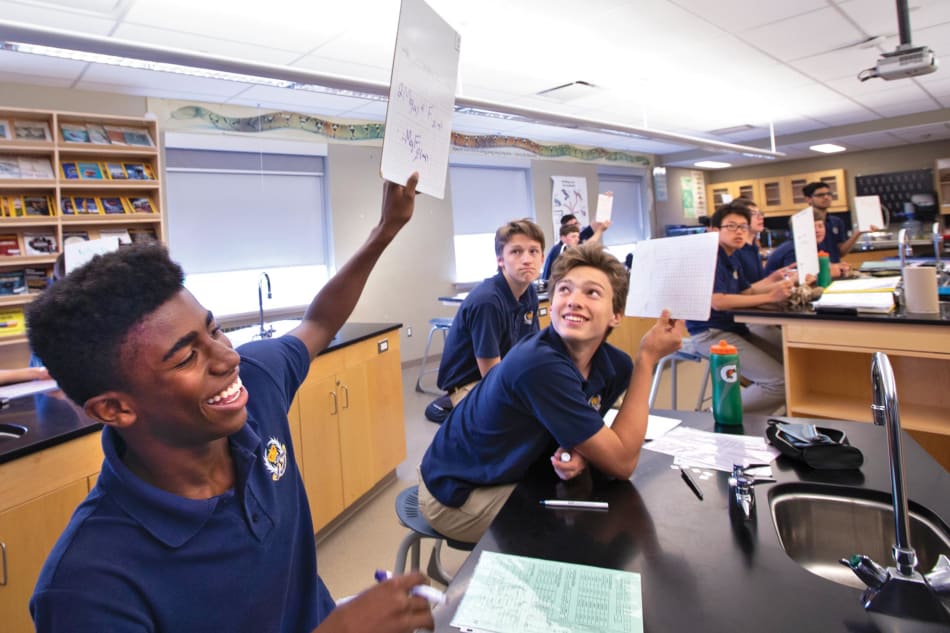

With whiteboards, movable furniture, and, in some cases, movable walls and partitions to create flexible spaces that can accommodate different pedagogies and different approaches, the instructional design of the new classrooms reflects an ongoing dedication to the core of the IB: group work and discussion-based, project-oriented instruction.

The classrooms, for the most part, are open and spacious and admit a wealth of natural light. Different areas of the classroom are used differently—and this is true in both the Prep School and the Upper School—depending on the task students are involved in, and modular furniture is used to facilitate activity and movement. Some spaces have adjustable-height desks, allowing students to stand, while others have Harkness tables. The understanding is that different students study in different ways, and it’s important to allow for collaboration around inquiry-based activities.

The flexible spaces have really come into their own. Whiteboards and smartboards circle the classrooms, with students getting up, moving about, and interacting with others. Mark Ferley, a Year 4 teacher, says, “retrofitting this classroom, we went with the tag line ‘less us, more them,’ ... [and] I feel that I am more in their world, as opposed to them existing in my world.”

Athletics and co-curriculars

The athletic program is a defining feature of the life of the school, made clear by the sports fields that dot the campus. The William P. Wilder ’40 Arena & Sports Complex is the newest building on site, and it houses two rinks: one to NHL standards and one to Olympic standards. The walls inside display photos of past teams and greats, including those who went on to play in the NHL. Hockey is the sport that the school has been historically known for, and that’s a focus that continues today.

All that said—and despite the prominence of the fields on the property—this isn’t a school where athletics are thrust, disproportionately, to the fore of the school culture. Throughout the athletic and co-curricular programs, the faculty regularly seek to affirm the concept of the students being their best selves, with achievement considered in personal terms, rather than exclusively in competitive/comparative terms. “I think one benefit of this school,” says Evans, “is when you’re sitting at assembly—Laidlaw Hall is full, and they sing a song, they all sit down—and they recognize different boys for different things: athletics, academics, music, fine arts, the whole gamut. It’s beautiful when you see your starting wide receiver on the varsity football team be introduced as one of the Blue Notes singers. Blue Notes is our acapella group, and they go up in their blazers, and there’s Johnny, our hard-nosed wide receiver, singing this beautiful melody. Or you have your saxophonist who is also your star shortstop. That well-roundedness—being able to dip into different areas of the programs—I think really makes it cool, and makes it safe, for all boys to delve into those areas. They don’t feel they have to be one-dimensional, and only be a jock, or an artsy person,” the stereotypical silos of high school life.

“Your view on high school when you’re younger,” says a boarding student, “is there’s the smart kids and then there’s the jocks. Here, everyone is everything. I do well in school but I still play two sports”—something he feels is common across the student population. Says Evans: “We like to think we’re a big school with big opportunities, yet we do our best to offer a small school feel, through a variety of different ways, so nobody falls through the cracks. … And because of the breadth of opportunity, everyone finds their niche.” It’s perhaps a function of being a boys’ school that they don’t feel so keenly the need to perform set roles, though that’s likely also a function of the character of the boys themselves. It’s not uncommon to find the star athletes taking part in school plays, or film, or Model United Nations—and that willingness to reach out, to risk trying new things, is a part of the culture of the school and emblematic of the kinds of students it attracts.

The Strength, Agility & Speed (SAS) Fitness Centre is as good a gym as you’ll ever hope to find anywhere, and it’s invigilated by a full-time trainer: “the legendary Mr. Guilford!” says a student, clearly in jest. A unit of the phys-ed classes for Years 8 through 10 are conducted in the fitness centre. Otherwise, varsity athletes are required to attend once a week, though many opt for more, and the facility and the trainer are available to any student who wishes to use them.

There is a focus on participation, and as a function of that, the teams are open to a wide range of participants. “He was able to get on the junior varsity basketball team,” says a parent of her son, “and he was able to get on to the varsity volleyball team, [though] he’d never played volleyball before.” A parent of the Prep School notes that the physical education program consists of one hour daily with a variety of units, including team sports and individual activities.

Outdoor education is centered around the Norval Outdoor School, a property UCC purchased in 1913 with the intention of relocating the school there. With the uncertainties of the war years, the move didn’t happen, and the property became an ancillary campus over time. A 45-minute drive from the main campus, it’s used throughout the year for teaching, especially around sustainability, stewardship, and physical education.

Student population

We asked a group of students to name any alumni of the school, and, to a person, they offered names of graduates that they had known personally, or who had come into the school as mentors or presenters. No famous names at all. “They’re not impressed by the pedigree,” says Emily Moir, vice-principal, enrolment management. “That doesn’t register with the boys at all.” And, truthfully, it’s perhaps nice that it doesn’t. They’re here because of what the school can offer them, not what it offered someone in the past. “I came here because I thought it was a good school,” says a boarder, a sentiment that is shared by a majority of the students. Fair enough.

“First, you have to think: is your child a good fit for the school?” says Evans. “Because it is academically rigorous, you don’t want to set anyone up for failure if they’re not inclined to do homework, and those kinds of things.” That includes being inclined to take a few risks, try new things, and make the most of a wide range of opportunities. While there’s a level of academic ability required to be successful in this setting, what sets the boys apart more substantially is an academic disposition: a desire to learn, and a willingness to put in the effort that academic success requires. While there are no guarantees in life, the boys are, by and large, talented and goal oriented, and the school unwaveringly supports them in all of that. “From my experience,” says a parent of the Prep School, “the boys have interacted well, successfully worked together in groups inside of the classroom as well as games outside of the classroom. There are also several ‘buddy’ systems with the older grades, such as reading buddies from the early years.”

“But I also want [parents] to know that we’re not the UCC of 20 years ago,” says Evans. “Parents ask me: if their boy isn’t passionate about athletics, is this going to be the right school for him? And I think, 20 years ago, that might have been a fair question. Throughout the many years I’ve been here the school has put in a concerted effort to make sure that our athletic program remains strong and expansive, as well as other co-curriculars, such as the fine arts, music, theatre, debate. These are valued just as much, and emphasized just as much, as our athletic program.”

UCC has grown and adapted to reflect the diversity of the surrounding population and the current needs of students. It offers more financial assistance, by far, than any other private or independent school in the country that are designed to ensure that it is accessible to a broad range of families. $5.2 million is available annually to families in need.

Common Ties

UCC has a sophisticated alumni support system, where they link up, in a formal way, various alumni in mentor-like relationships. The program is called “Common Ties.” If you find yourself in, say, London, or New York City, or LA, or Tokyo, or Dubai, there will be an ‘embassy’ of UCC alumni there to greet you and help you integrate.

Well-being

Well-being is a core value at UCC — grounded in the belief that it’s important for students to have a sense of autonomy and feel like they have influence in their school, because that engagement and ownership of their school life deepens their connection to their school culture. UCC’s ongoing process of re-examination around personal well-being includes the appointment of Dr. Alejandro Adler as dean of student life and well-being. Resiliency is a focus, and it is somewhat emblematic of our time. “One of the most important things for a student to leave any educational institution with,” says McKinney, “is perhaps the hardest to teach, and that’s confidence. …. It’s experiential, built on little successes along the way that develops that self-belief. Where does confidence become over-confidence, or false reality? And that’s where I believe the emphasis we are undertaking in the area of well-being [comes in], which is around the importance of not succeeding at different points in time. … If I don’t succeed, that’s important for learning.”

“I think we have a responsibility to help people understand the importance of humility, gratitude, empathy, and true acceptance of different perspectives and difference.”—Sam McKinney, principal

That’s perhaps especially true in the rarefied environment of UCC, in which examples of success are rampant, from the Old Boys and alumni who have endowed development, to the boy sitting next to you. To provide an antidote is something that faculty have dedicated themselves to, in some degree.

Says McKinney: “We do understand the challenge of stress and anxiety and how that manifests in individuals. I think we have a responsibility to help people understand the importance of humility, gratitude, empathy, and true acceptance of different perspectives and difference.” Active programming helps bring that about, as do the structures that exist within the school to mediate the student experience. Boys are all assigned to a house when they arrive, and they stay within it for the duration of their time at UCC. They also have a form adviser and meet in their forms regularly throughout the year. “During our advising periods,” says one student, “our form adviser sends out topics for discussion that are very thoughtful about mental health and world issues.”

The well-being staff includes a psychologist, clinical social workers, registered nurses, and an athletic therapist, Sonya Pridmore, who has managed the UCC sports injury clinic since 1994. Students are also assigned to a university counsellor whom they meet with regularly in offices just off the student centre.

Admission

The admission process is about assessing promise and potential as much as experience. UCC is aware that “if it’s only about the CV, then you fall short, and you will continue to exclude those who have already been excluded. And that’s the challenge. As a result, the interview is a significant element of the admission process, because that’s where you can, as an experienced educator, have a conversation and be able to understand what they’re dreaming about, what are their hopes and aspirations, what do they want, how can they reflect on their past and think about their future. The interview is not the most scientific way to gauge ability or potential, and it also isn’t the only factor for consideration. Nevertheless, it’s an important tool, given that the school posits the learning experience in broad terms, and principally as a relationship between a boy, his family, and the school. It’s about “getting to know the person as an individual, their co-curricular pursuits, and getting to understand what they’ve been through and how they see the future as a result of that.

There is a false perception that legacy families are accepted preferentially, and that a sizeable portion of the student body are sons of alumni. In fact, the admission process doesn’t use legacy as a selection criteria, and only a small portion of the students enrolled fall within that category. There are some, of course, though not out of proportion to what you’d find at any school of similar academic mandate. The admission team is more interested in enrolling students who are a good fit for the program and are likely to thrive within it. Academic ability is, of course, an important criterion, though it’s not the only one. The school is interested in boys who show a breadth of interest and intellectual curiosity, and who will be comfortable in a co-operative academic environment. There may be a school somewhere that is looking for solitary geniuses, but UCC certainly isn’t it. The atmosphere is social, collaborative, and active, and the school is particularly keen to enroll boys who can make the most of the entire offering.

Parents report a satisfaction with the tone of the admission process as well as their children’s acclimatization to the school. “From the time of entrance to the school,” says a current parent, “new parent events are held where questions are answered and parents are given the opportunity to engage not only with faculty, but with current parents. This continues as the school year begins with coffee mornings and parent receptions. Parents are welcomed to the school regularly for events, in-class learning displays, whole-school community events, and the opportunity to bring their expertise into the classroom when the learning fits.”

Tuition and financial assistance

Tuition is, as you’d expect, commensurate with the size and scope of the program. The financial assistance program is far and away larger than most would expect, and it’s the biggest of any private or independent school in the country. Admission is based on academic strength and breadth of interest. Financial assistance is awarded based on demonstrated family need. The impact is felt more in the Upper School, perhaps understandably. Year 5 is seen as the year that the school is able to predict with a bit more certainty the potential of a boy and his ability to benefit from what the program offers.

The ability to provide that kind of financial aid is a product of the unequalled fundraising power of the school. UCC raised 100 million for its capital projects and financial aid program in 2016. That’s a testament to the commitment of alumni to the school. An alumnus who went to both UCC and Queen’s University told us that “I chip in some money to UCC. I don’t do that for Queen’s,” something he feels is simply a reflection of the place the school holds in his life and, perhaps, his heart.

Parents report that fees meet their expectations, though there are incidentals through the year depending on the activities a boy chooses to be involved in. Incidental costs are listed on the school’s website so parents can plan ahead and anticipate.

Tuition is, as you’d expect, commensurate with the size and scope of the program. The financial assistance program is far and away larger than most would expect, and it’s the biggest of any private or independent school in the country. Admission is based on academic strength and breadth of interest. Financial assistance is awarded based on demonstrated family need. The impact is felt more in the Upper School, perhaps understandably. Year 5 is seen as the year that the school is able to predict with a bit more certainty the potential of a boy and his ability to benefit from what the program offers.

The ability to provide that kind of financial aid is a product of the unequalled fundraising power of the school. UCC raised 100 million for its capital projects and financial aid program in 2016. That’s a testament to the commitment of alumni to the school. An alumnus who went to both UCC and Queen’s University told us that “I chip in some money to UCC. I don’t do that for Queen’s,” something he feels is simply a reflection of the place the school holds in his life and, perhaps, his heart.

Parents report that fees meet their expectations, though there are incidentals through the year depending on the activities a boy chooses to be involved in. Incidental costs are listed on the school’s website so parents can plan ahead and anticipate.

The takeaway

Upper Canada College (UCC) is one of the oldest and most storied schools in Canada. Its alumni include a who’s who of Canadian political, business, and cultural life. Its history is, in many ways, the history of independent schooling itself; to attend is to become a part of a Canadian cultural tradition, one that retains a prominent place in Canadian education. The school leads in the provision of financial assistance, intended to attract the brightest students regardless of their financial circumstances.

American journalist and political commentator Bill Moyers once said that “the most heroic of all acts is the courage to discover who you are and what you would like to be.” In a very real sense, that’s the understanding that informs the program that UCC offers today. It’s not a place to become good at one thing, but rather to grow in all areas of your life, to indulge existing curiosities while finding new ones. The coursework is challenging, and the school demands a lot of the boys who enroll. When they enter, they join a community of constituents—students, faculty, alumni—that is supportive and encouraging, and which demands that all, in turn, offer their own support and encouragement. Success is a function of how deeply you can connect with the culture of the school and take advantage of the full range of experiences and opportunities it offers. UCC is looking for students who are prone to just that.