Rosseau Lake College THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of Rosseau Lake College, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Introduction

“I had a bit of a crush on Rosseau Lake for a long time,” says principal Graham Vogt. While working at other independent schools in various roles, he says the school always exerted a pull, partially because of where it was—it’s easy to harbour dreams of a life in this part of the world—though more for what it was. “The outdoor focus was appealing,” he says, “and how that intersected with the delivery of the curriculum.” Vogt says he and his wife, who is now also on faculty, “idealized it as a place where our own personal pedagogies, based on our own values systems, maybe would have a chance to take off and thrive. … In the summertime, whenever we were in this area, we’d drive by, sometimes drive in, and just wonder, ‘What if?’”

If there is a tradition at Rosseau Lake, existent from day one, that’s it in a nutshell: a shared set of values and pedagogies, and a disposition to ask, “What if?” The school was founded by Roger Morris and Maurice East, both of whom weren’t professional educators, though they believed in the power of education to change a young person’s life. The founding headmaster, Ronald H. Perry, felt the same way. He was an amateur naturalist and expert canoeist. During the war he was a squadron leader in the RCAF. Perry had recently vacated his position as headmaster at Ashbury College in Ottawa, seemingly content to step away from his career in education and settle into retirement. When he learned of the concept of Rosseau Lake, he changed his mind. He would serve as head at the school for the next eight years.

Morris, East, and Perry were moved by developments in the world of education around experiential learning and were directly influenced by the work of Kurt Hahn. As an educator, Hahn founded schools in Germany and the UK, as well as three co-curricular programs that are now delivered around the world: Round Square, the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award, and Outward Bound. All expressed what Hahn wanted education to do—or what he felt education could do better—namely to give students a sense of purpose and prepare them in mind, body, and intellect to go out and change the world for the better. Today there are terms for this, including outdoor education, wholistic learning, and experiential learning. While Hahn didn’t use those exact terms, every school that does, including Rosseau Lake, is referencing the impact he had. Famously, Hahn believed “there is more in us than we know.” It’s that idea that animated the founders to create a school. When a property came available—56 acres in a natural setting, on a lake, with some buildings in place—it was that question that tugged at their lapels: What if?

Key words for Rosseau Lake College: Community. Gratitude. Resilience. Authenticity. Diversity.

Basics

Rosseau Lake College (RLC) is an independent coed day and boarding school offering Grade 6 through Grade 12. It was established in 1967 as an all-boys’ school—it became coed in 1983—on a rural property in northern Ontario, on one of the province’s most famous lakes, about a 2½-hour drive north of Toronto. Dotted with pristine lakes and tracts of hardwood forest, the region can feel a world away, though it’s hardly the back of beyond. Known for its rugged beauty, it’s also one of the busier tourist destinations in the province, receiving in excess of two million visitors annually. Muskoka has long been a prized location for the development of summer homes, and that’s more true today than ever before. Properties range from modest cottages to mansion-like summer estates. Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks, Mike Weir, Cindy Crawford, Martin Short (who has a home right across the lake from the campus, and has visited a number of times) among many others, all have summer homes here.

The school sits at the northern tip of Lake Rosseau on a wooded lot that includes 3,300 feet of lakefront. It’s a small school in all the best ways: intimate, active, and personal. The student body is evenly divided between international and domestic students. Those arriving from overseas represent in excess of 20 nationalities and 19 dialects, which is remarkable—few schools, let alone one of this size, attract such a diverse range of international students. A majority of students board on-site, and a majority of the teaching staff do as well.

The property was once home to a grand Edwardian estate, though the buildings from that time are now long gone, replaced by those that are more sympathetic to the natural environment and matched to the thrust of the academic program. Today the campus has a traditional, delightfully modest feel. There are outdoor classrooms, including a teepee and a natural amphitheatre by the water’s edge, which instructors make consistent use of. Windows line the indoor spaces, ensuring the outdoors is a constant presence in the student experience.

The approach to all aspects of student life is challenge by choice, encouraging students to reach further in terms of their academic, physical, and social development. In addition to mastering the core curriculum, students are asked to consider how they can serve their communities, and they are given ample opportunities to do just that. Those communities include the First Nations for which the area is home and who partner in many of the programs offered.

Outdoor education is a focus, and the campus is a prime resource in that regard. There are canoes, climbing walls, kayaks, sailboats, and a snowboard terrain park. Trails throughout the campus are used for hiking in the warmer months and snowshoeing and skiing when there’s snow. In all seasons, in all weather, students spend a good portion of every day outdoors, sometimes in physical activity, other times just drinking it all in. “I took it for granted when I was there, because that was my normal,” an alum told us when thinking of the hours he spent outdoors. “I think back at my time at Rosseau, and it almost doesn’t seem real.” The natural environment, even when students are indoors, plays a prominent role, and the experience the students have outside the classroom feeds the experiences they have inside.

The architecture is reminiscent of summer camp and was designed to echo that kind of collaborative, outdoor environment. There are brown buildings with red trim, in keeping with the context and, to some extent, the cultural history of the Muskoka region. It all feels very familiar. The location is somewhat remote, if not isolated, and students don’t tend to leave campus in the way those in urban schools might. That’s seen as a great strength of the property: when students are here, they’re really here, able to focus on their work and engage with the people they share the school with.

The winters can be cold and long, though there’s a sense of getting through them together, as a team. Kids dress warmly, and away they go. Says a recent alum, “Almost without fail, every spare I had in the winter, I’d throw on my snow pants, my big winter coat. I’d find someone else who had spare, and we’d go sledding; we’d go build snowmen. One of my favourite pictures I have from RLC is this big snowman I built on spare in between my math classes. We had 50 minutes, and we just went outside and built a snowman.” Reflecting on that thought, he adds, “Winter is awesome.” Perhaps there are moments when it isn’t entirely enjoyed, but all agree it adds to the sense of place and the shared experience of it. (Past head of school Joe Seagram once said, “Nature is a great leveller.”)

Resilience is a word that comes up often in speaking with staff, faculty, and alumni. What other schools call character education and hive off into a separate area of programming is more integrated within school life itself. As an alumnus told us, “It’s a great place to learn who you are as a person, grow more, try new experiences you won’t necessarily get anywhere else.” The experience of winter is one of them.

Background

Rosseau Lake College was founded and remains on a property that was once the Eaton family estate. They were owners of a national chain of wildly successful department stores, renowned for their wealth. It’s easy to imagine high tea on the lawn in front of a colonnaded mansion, and for a time in the 1920s and 1930s, it was that kind of place. There really was a mansion; there really were columns. Ironically, perhaps, the only building that remains from that time is the most rustic one: a log cabin Lady Eaton used as a sewing room. (It’s been suggested that she employed it as a means of getting away from the family in the main house.)

Lady Eaton never liked the estate, preferring to stay in the city, and in time that’s exactly what she did. The family sold the property to the government during the Second World War, and it was used as a rehabilitation centre for returning soldiers. It later became a private lodge, the Kawandag Resort. Morris and East took over the property in the mid-1960s, a bit unsure of quite what to do with it. It occurred to them that it would be an exceptional location for a school, so in 1967, they and a band of intrepid teachers mounted a summer session. It went well, there was interest from families, and the first full academic session started in the fall of that year. There were five staff members, in addition to the headmaster, who also did some teaching.

There were 27 boys in the first cohort, and founder Roger Morris’s son Bill was one of them. He remembers it as a unique time. “Part of our curriculum was helping improve the school,” he says. That included everything from raking leaves to picking up brush to tending the extensive gardens. Physical exercise was an important part of daily life, and everyone was encouraged to be active. While we might describe it as outdoor education today, at the time, says Morris with a chuckle, “we just didn’t know any better.” He loved it. “There was plenty of time to explore, and we still had all the outbuildings of the estate. … Some of the best times of our lives were with guys who really did become our brothers.” The students were mostly Canadian at the start, though the school was already attracting international attention. In Morris’s year there were boys from Bermuda, the US, Trinidad, and the UK. By the time Morris graduated, the school had quadrupled in size.

At that time, all of the school’s buildings dated from the turn of the 20th century and were framed in wood, and they suffered the fate of so many buildings of their vintage. In 1972, the main building was consumed by fire. It had housed much of the infrastructure of the school, including classrooms, the headmasters’ residence, and key recreational spaces. Morris was still a student then, and he recalls that Perry, the headmaster, was visibly heartbroken. “He looked like a broken man.”

The loss was understandably a huge blow, and the idea of recovering from it wasn’t something many at the time could reasonably conceive. A meeting was held at the Royal York Hotel in downtown Toronto to announce to the primary stakeholders that the school would be discontinuing operations. The board members were there, as were students and parents. Bill Morris was there, too. He recalls that, at least at the outset, it felt like a wake, with the headmaster laying out the reasons they really didn’t have any choice but to close. But then the mood changed from one of resignation to one of possibility. A parent asked why they couldn’t bring in some temporary buildings. As it happened, one of parents—a man who would later go on to serve on the school board—was a senior vice-president for TransCanada Pipelines. He had experience building temporary work camps and felt he could do it here as well. Someone else asked how the school could get insurance, given that it has just come through a fire. Says Morris, “So somebody else who was in the room was a senior insurance executive, and he says, ‘It wasn’t your fault. As long as the facilities that are in place are of a good quality and meet building code standards, insurance won’t be a problem. I’ll guarantee you’ll have insurance.’” And on it went. When someone wondered out loud how they might pay for permanent structures, Morris recalls people simply opening their chequebooks and asking, “Okay, how much do you need?”

“When I think about it, it was pretty emotional for everybody,” says Morris. There were a few students who spoke, including the head boy, who said, “The school is about survival.” Within several weeks there were temporary 15-person dormitories in place, and two trailers had been joined to create a workable canteen. School was back in session while, concurrently, plans were being drawn for the new campus.

That meeting has entered the mythology of the school, a touchstone for the sense of community and resilience that remains even now. “It was nothing short of miraculous,” says Morris. They had solved the problem of how to continue, though it was more than that. It was a moment that galvanized the core values of the school and its reason for being. “We’ve always been a school that’s a little bit different. I’d like to believe that, now, that’s the fundamental school value—it doesn’t always get talked about, but the concept of resilience, of figuring it out.”

Vogt says the 1970s rebuilding and the years that followed had a lasting effect on the school “The reason the school is important to us is because we feel that’s part of our fabric. … We are a school that finds its way through challenge and helps students find their way through challenge. It’s a place to build an amount of resiliency and resolve—ideally, not because our viability is being tested,” he adds with a chuckle. “I don’t think it’s been that school for a long, long time. But that is at the core. It seems to be a part of who we are.” There is a sense that Rosseau Lake College was founded by a community that shared its values, including the passion and tenacity to keep going. And, through it all, that passion, tenacity, and sense of community is still here.

Leadership

The school has had twelve heads since it was founded. They were first known as headmasters, though now the title is “head of school.” The current head of school is Dave Krocker, who arrived in 2021. When we met one morning, instead of sitting in his office, we walked a trail that circles the campus. On the way we stopped at the teepee near the entrance to the property, which was a gift from the Wasauksing First Nation, and is maintained by members of that community. Krocker noted that that morning he had hosted a staff meeting there. We ducked through the entryway and stood on either side of the firepit. After a moment he said, as much to himself as to me, “Isn’t it great?” It really is. “As I said when we were in here this morning, this is maybe the most unique faculty meeting that I’ve ever had.” The embers of the fire were still glowing, the smell of the woodsmoke still in the air. The fire had been lit for warmth—it had been a cold fall morning, snow seemingly not that far off—as well as all the other things we associate with a campfire: gathering, sharing a moment, looking at something other than screens.

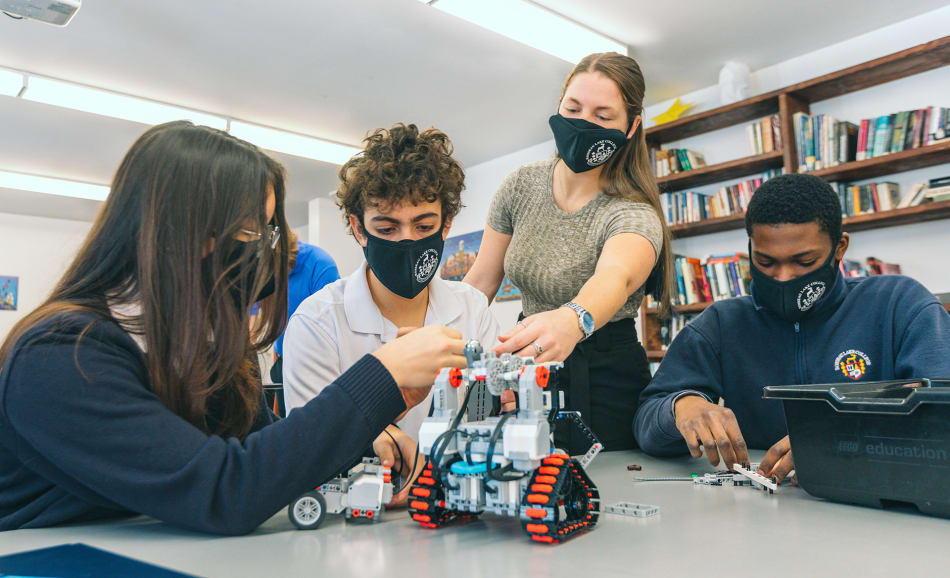

The connections with the First Nation communities and the uniqueness of having such a range of learning spaces are things that Krocker visibly relishes. One of the things that he loves about RLC is how the campus disrupts expectations and, in turn, encourages new ways of thinking, inspires new ideas, and develops deep relationships. “We need to be building innovators, creators, thinkers, problem solvers, communicators,” he says. Just as important if not more so—actually, when he said this, it was clear that this was the more important end of the equation—“we need joyful, good people.”

All of those things—innovation, disruption, joy—have arguably been the defining aspects of Krocker’s career in education. When he started his career in Alberta, the province had just launched the Alberta initiative for school improvement. As a result, he and two colleagues found themselves in the enviable position of having a million-dollar grant with which to improve education, seemingly in any way they saw fit. “We blew it up, literally,” he said, meaning that they used the grant to redesign the school and, with it, the style of academic delivery used there. They removed walls and partitions; “we combined the entire thing into an experiential humanities program.” The smaller spaces that had been there prior—no doubt set with rows of desks facing the front of the room—were repurposed to allow for collaboration, experiential learning, and a move away from chalk and talk. After the redesign, the students would meet in groups, facing each other rather than the front of the room.

It wasn’t about being different just to be different, just as true innovation isn’t just doing the opposite of what’s been done before. Rather, as Krocker describes it, it was a renegotiation of the learning experience with the intention of granting the students the skills, postures, and literacies that they would need as they moved ahead in education and in life. Times were changing; this was near the advent of the digital age. These were kids, in his estimation, that would need to work together to solve problems, rather than recalling facts or rendering data. Yes, math was important, but so was delivering your thoughts and ideas effectively while being attentive to the thoughts and ideas of others. Krocker sees that experience—having the responsibility but also the freedom to think in bold ways about education—as a defining moment in his career. “I was a brand new teacher, and that really set the appetite of thinking differently about learning and the possibilities of teaching.”

From Alberta, Krocker set off to see the world, eventually filling administrative roles at the International School in Bangkok, Lakefield College School, and the Colegio Interamericano in Guatemala City. “I have a very strong sense of adventure, no question,” he says. “I’ve always loved that sense of, ‘I don’t know this, and I’ve got to really figure this out.’ That sense of actually not knowing the answer, of not being comfortable. I loved being pushed.” When I ask what he feels the hiring committee at RLC saw in him, he says “I think that experience and exposure to the world, that sense of the possibilities of what can be.”

On the face of it, RLC doesn’t look much like those schools in Bangkok or Guatemala City. They aren’t located on lakes in rural Ontario, for one. But what they share is that they attract students from around the world. Within them, success requires that students learn to work together, as uncomfortable as that can be at times. It’s a style of learning that RLC excels in, which was Krocker’s attraction to it initially. Getting kids from around the world managing a canoe trip, for example, can be a uniquely valuable learning experience in lots of unforeseen ways. Which is why he says, “I believe our major strategic advantage as a school is our diversity.” It grants a sense of the world, yes, but also “the challenges of a true multicultural environment.” Simply by living together over the school year the students naturally navigate cultural norms, become aware of their own and others’ sensitivities, and learn how to fit into a community that, at times, can present competing interests.

Krocker has said that leadership is about reflection and asking the right questions, “making sure that you take the time to consider all angles.” He was brought on, in part, to bring that kind of deliberate reflection. He’s notably keen to listen, and as we talk, he comments on things that he took away from a recent parent survey. The parents had praise, but also posed some hard questions, including a pressing need for additional staff housing. He says, “I love that our parents are identifying these things.”

He listens to the students as well, stopping to talk with them as he moves about the campus, and makes a point of meeting and greeting them every morning. “The best ideas come from your users,” he says. “The kids live this—they eat the food, they sit in the classrooms, they live the schedule we create—and they come up with the most amazing ideas.” This is as much about what the school is doing right as it is about things they feel could be improved. To be sure, that kind of student agency is something he holds close to his heart. He speaks of a recent survey that was created and completed by students. He gave them the headings—campus life, academics, co-curriculars, food service—and asked them to design questions because, simply, “they know the right questions to ask.” Students were involved after the data was collected as well, gathering the feedback and using it to inform action strategies. “They have to be part of it, because they know it.”

In his time as the head of school, Krocker will oversee a major capital campaign. It will bring new facilities as well as upgrades on existing facilities. That could mean a bold departure, though Krocker’s intention is to keep things traditional and sympathetic to the school’s history and the region of the world it sits within. He anticipates growth, though he is careful with that concept, knowing that growth can mean different things. “I think the growth we’re looking for is to become even more intentional about the value of relationships.” That’s something that has defined the culture of RLC since its inception, but he knows that it shouldn’t—in fact, that it can’t—be taken for granted. He says, “the other area of absolute growth that has to happen is around sustainability and innovation, of really developing stewardship.” Environmental stewardship is part of that—it’s hard to imagine a school that lives this closely or as in tune with the natural environment—but also stewardship of the community of the school and, ultimately, all the various communities that the students will participate within as they move on in their education and their lives.

Krocker feels that the campus, both through its size and location, has a unique ability to bring all of those things forward. That the place, ultimately, plays a role. At one point during our walk we pass a copse of trees where an outdoor ed class had recently slept out in hammocks. “I don’t know of another school where, you know, when it’s going down to two degrees at night, there are kids happily sleeping outside.” There are very few schools at which it would even be an option.

As we walk we spot some fresh deer tracks. Moose are here from time to time. Closer to the shoreline there are some buildings from the original estate which reflect the historic use of the property. Turning, there’s the view across the lake. After a pause he says, “I’ve really landed somewhere special.” It’s clear that he’s not thinking of the natural beauty, or at least only of that. He feels that this leadership role, at this school, at this point in time, is one that his career to date has been preparing him for, if not overtly pointing toward. “This needs to be the best small school in the country” he says. No doubt, if it isn’t already, it will be.

“Setting goals is so important in all aspects of life. … In many respects, outdoor education is about setting goals.”

—Joseph F. Seagram, headmaster 1999–2008

Academics

In 2018 Graham Vogt was hired as the director of academics. His mandate was to oversee the academic program while making the learning even more immersive in the outdoors, further blurring the lines between traditional academic delivery and outdoor education. “We’re an experiential school,” he says. “We believe the best learning happens when it is immersed in experience. … One of the things we know is that when we create that experience, we help the learning to be applied in alternate settings, and it resonates more strongly with students.”

There are certain subjects that lend themselves more to the outdoors, such as geography, history, and the sciences. The challenge, says Vogt, is to figure out how others do as well. A current Grade 9 student told us about how her English teacher asked some of the students to go outside and use descriptive text to write about something they saw. Then, with only those descriptions in hand, others went out to see if they could find what they described. “Also, for most of our science we were outside, at the lake, studying the physics of canoes—learning about Newton’s three laws and how they apply to canoeing.” When she described it, we could hear her smile through the phone. “It definitely made it a lot more enjoyable than just sitting in a classroom and working by textbook all day.” It’s also a good example of what Vogt means when he talks about experiential learning being more lasting. That student could tell us all about Newton’s laws—with more animation and enjoyment—because they were part of that experience she had, with others, in canoes on a lake one sunny fall day.

“That’s our balance as a school,” says Vogt. “We believe strongly in the outdoor experience and what that provides for students both as learners and as people.” He means that in the broadest sense, and not limited to just a canoe trip once or twice a year (though they do that, too). As a current parent told us, “It’s a when-in-doubt-get-out-and-enjoy-nature kind of philosophy.”

• • •

Rosseau Lake is a preparatory school in the classic sense. All the students are preparing to enter post-secondary programs, and as they approach Grade 11 and Grade 12, instruction focuses a bit more intentionally on that next phase of life. Learning becomes a little more classroom focused, in part because of the demands of the curriculum, but also in part to acclimate the students to the more standard academic settings they’ll move into.

Academics are rigorous, following a progressive liberal arts model. The average class size is between 10 and 15 students. There are aspects of the school that remain more traditional, such as having students sit final examinations, but even those are viewed through an experiential lens. “We’re not so worried about exams as an outcome that measures learning,” says Vogt. “We are a little bit, but we’re much more concerned about providing the experience of exams and the opportunity for students to build identities as exam takers. … We treat them as formative experiences.”

The school, understandably, attracts teachers who are committed to outdoor education. All are dynamic, creative, and self-starting. Currently there are staff from Nunavut , Nova Scotia, and everywhere in between; many have international teaching experience. As a current Grade 9 student told us, “My math teacher makes all these puzzles and stuff for us to figure out. … We’ll go around the school and find clues with math.” As if reminded, she adds, “And, oh, my English teacher, he does these really cool things where you get through your work in fun ways, where we can still get everything done but less painfully [than in a more typical academic setting].” You can tell, even over the phone—we connected with her at home during the pandemic—that she’s beaming ear to ear as she talks about math, English, and her teachers. “And my outdoor education teacher always has something on the go. … One time he threw us out in the bush and told one person to go find an object and then to lead their partner around—not touching them, not giving directions—just to describe the general area and what the area looks like.” As evidenced in the tone of her voice, she loved it.

“We spend so much of our time behind screens. Let’s get out from behind the screens. Let’s get out there and do. And I think that is the essence of what our school does.”

—Tia Saley, Teacher, Round Square coordinator

Rosseau Lake doesn’t offer the International Baccalaureate (IB), though it shares many attributes with those that do: the geographic diversity within the faculty, for one. It also shares the tradition of thinking globally—the IB is heavily influenced by the work of Kurt Hahn—particularly in the sense of global citizenship, which has been a core feature of Rosseau Lake’s DNA since its inception. Learning experiences are stretched out over longer arcs of time. The school year is semestered, so courses are offered over a period of months. That’s mirrored in the daily and weekly schedule, with longer blocks of time in the afternoons for students to get involved in projects in a deeper, more committed way. Because of the variation of the daily schedule through the week (Wednesday afternoons, for example, are on a flexible schedule), there isn’t a sense of being pushed from class to class, discipline to discipline, whenever the bell rings. Instead, there is time offered to get into a task and stay with it, largely free from pesky distractions. The dissection of a frog, for example, might take a whole afternoon. As well it should. This is a school that believes in the value of taking time, that learning is an experience to be savoured.

Instruction is project based, and there are many points within the academic calendar for students to engage in bigger projects than more typical coursework would allow. There are Term Courses every January and May, and month-long projects. When we spoke with teacher Tia Saley, she was in the middle of the May term, teaching a course in environmental science. “It’s a bit of a bummer, because I was so excited for it to be a month-long field course,” which, outside of a pandemic, it would have been. “We would be outside all day, every day, literally getting our hands dirty.” Instead, she made the best of things, convening students online—all day, every day—with study in the evening. “I based it on the four elements: earth, water, air, and fire, and tied in environmental issues that go with each element.”

During Earth Week they talked about soil and planted things wherever they were (some international students were distancing on campus). “You could re-root a carrot top, say, and over the month, they are emulating an environmental issue with their plants.” Those on campus built a butterfly garden and planted vegetables. One of them was Ouelhore Diallo, a Grade 11 student who arrived from Tanzania. “We dug up some trees. We were planting beans, zucchini, and corn. And then we did some experiments on them because we had to do a lab report.” These are the Three Sisters, a tie into the Indigenous curriculum. “The corn grows tall, the pole beans grow around it, and the squash grows flat on the ground. So they all support each other.”

Similarly, during Water Week, students debated “to dam or not to dam” and did research on the pros and cons of a fictional dam ostensibly proposed for Lake Rosseau. “It’s all very hands-on and tactile,” says Saley, “which is the purpose of the January terms and the May terms. You’ve got this month-long immersive course. For my students now, they’re eating, sleeping, and breathing environmental science.”

The academic year culminates in Discovery Week, during which students complete and present a project of their own design, applying and demonstrating the knowledge and skills they’ve developed throughout the year. It’s a design-process project that begins in January. From then on, Wednesday afternoons are given over to the project. It begins in entirely blue-sky, out-of-the-box thinking, with students considering their passions and the things that animate their imaginations, and then working ahead from there. They are also required to tie their projects back to the courses they’ve been taking throughout the year. “So the kids who are in my class,” says Saley, “their Discovery Week project has to have an environmental component.” She says that could be an environmental issue or environmental impact. “But then they have to tie it back to math or into the content of their English course.”

There’s a formal scaffolding that takes the projects through design to creation to presentation. “Say some kid wants to build a tree fort. Okay, great. What are all the steps you need to do in order to build a tree fort? What supplies do you need? What’s your location? What skills do you need to learn beforehand? The idea is that they put together their proposal,” Saley says. Recent projects range from auditing the effects of road salt on the local environment to designing and marketing a line of lip balm products to designing and building a motorized car. Afterward, students reflect on what they’ve done through a presentation. “It’s not based on, you know, did they build the best tree fort. It’s what did they learn from trying to achieve that?” That means everything from measure-twice-cut-once to creating a workable budget. “There’s a wide array. We’ve got one girl who’s doing a net-zero diet, but she’s trying it for a month leading up to Discovery Week so she can do net-zero for the entire week,” Saley says. In that case, the reflection is on the net cost of her life, essentially her carbon footprint. “It’s beautiful.”

Using design thinking, in the Discovery Week process and beyond, is a thrust of the academic program. Rote learning and sitting behind a desk isn’t the way things are done. “We want to learn alongside you,” says Saley. “We’re here to help you and to guide you and to definitely point you in the right direction, but we also want to give you hard and soft skills.” Getting out in doing, out from behind the screens, being immersed in the work at hand. “That is the essence of what our school does.”

“[There was] good communication by the teachers, explaining content, and why it was important, [they were] great at providing constructive feedback, and also making time for extra assistance if required. We had more frequent academic monitoring than public school systems, and as such, the teachers were aware much sooner if we were not understanding or struggling in any way and would immediately assist in correcting that, usually with extra help, student tutoring, or extra study time.”

—Jenny Spring, ‘05 alumnus

The school follows the Ontario curriculum, and students graduate with the OSSD, though the progress through the grades is highly sequenced and unique to Rosseau Lake. Grades 6 through 8 are the Foundation Years, which, as the name suggests, are designed as a time to develop a good basis in the fundamentals. Instructors work closely together so that when students move up, their strengths, challenges, and talents are known. The school prizes individual, student-paced learning. Says an alumnus, Jenny Spring, “I felt like the teachers paid attention to people’s learning skills, how they learned, and how that was different from student to student.”

With the size of the school, all students have access regularly to whatever support they might need. Further, there’s an understanding that every student can benefit from personalized learning—every student has their strengths and their struggles—and staff use the term Individual Student Strategies in order to refer to the formal structures around that. Rather than having a majority of students on a common plan with a few singled out for modifications—as would be the case in a typical school—all students are granted a personalized learning strategy.

Academic environment

The formation of the school coincided with the Canadian centennial celebrations, something not lost on the founders. The first prospectus, printed in 1966, read, “As Canada prepares to enter its second century, there is a pressing need to equip its future citizens socially, morally, and intellectually so that they may meet the challenges of ensuing decades with courage, intelligence and understanding.” These weren’t people given to thinking small. It continues: “The nature of the terrain—Canadian lake and woodland … is such that academic studies will be blended with unique outdoor recreation programmes, all of which will be distinctively Canadian.”

The school remains very much that today, if not more so. It sees itself as entirely unique, and indeed it is; it works to blend the setting with the delivery of the academic program; and it prides itself in having an ethos of intelligence and understanding. There are some obvious comparisons to summer camp, and while it’s possible to take them too far, there is also value in recognizing what Rosseau Lake shares with non-academic outdoor programs. The buildings are reminiscent of summer camp structures and the social environment is as well. (Classes are held in the RAC and the Perry Building, both of which are modern, though fittingly modest, in keeping with the campus feel. Indoor spaces are bathed in natural light, with windows out to the grounds and the lake beyond, such that, even inside, there is always a connection to the outdoors.) “We do very camp-like things, quite frankly,” says Vogt. There are camp-outs on the property. There’s an informal polar bear club, with staff and students challenging themselves to get into the lake at least once a month throughout the entirety of the school year; when there is ice on the lake, a hole is cut through it with a chainsaw. There are regular coffee houses, where students perform songs and skits. In warmer months, many go for a morning swim before breakfast.

The entire school gathers in a circle every morning. “We’re all looking each other in the eye and noticing each other,” says Bissonette. They sing and make announcements. “It’s very special.” The circle is seen as a symbol of the school community, granting a sense of a whole that staff and students carry with them into their days. The feeling, says Vogt, is that were the student body to ever get so big that standing together in a single circle was no longer possible, that would be a point when they would know the school had become too big. “What are we after that? I think it’s probably an identity crisis,” says Vogt, chuckling. He’s making a bit of a joke, but he believes it all the same. Size and identity are two sides of the same coin. And beyond a certain threshold, the school as people know it would cease to be.

They turn off the internet for a few hours every Saturday afternoon. The kids don’t love it, at least not at first, says Vogt. “But we don’t worry about what they say in the moment—we worry about what they say when they’re leaving us at the end of Grade 12.” At which point, they’ve come to appreciate it.

“One thing RLC taught me is to step out of my comfort zone, and it is all because I had teachers and friends around me to push me and encourage me...I’ve learned that challenging myself is a pretty exciting thing and failure is not the end of the world. Just keep going and keep trying.”

—Siyun Zoe Shao, ‘21 alumnus

Outdoor education

In many schools, outdoor education programs are secondary, offered only as co-curricular activities. At Rosseau Lake, they’re integrated throughout the day and the curriculum. There are annual events, including theme weeks; in 2021 they had an Earth Week, with each day presenting opportunities to think about different aspects of the natural environment. Included were lessons from Kory Snache-Giniw, the Seven Generations lead, on Indigenous topics relating to the theme. (“It gives us a whole new perspective,” says Vogt.)

Assistant Head of School Cheryl Bissonette describes the program as a land-based education, in part to suggest that it’s not just going outside and doing hiking or canoeing instead of phys. ed. Rather, instructors are using the outdoors every day, capitalizing on all the experiences and activity it can offer and weaving them through the curriculum. “We talk about our graduates being prepared for life—not just post-secondary programs,” she says. “The land-based, the environment connection is that appreciation and that skill base that’s going to carry them for a lifetime.” She and others at the school relate the sense that learning in the outdoors—in the immersive experience of the environment—adds depth to the learning itself. Says Bissonette, “The kids are more engaged, and therefore it’s different learning. And with that comes learning that’s going to be sustainable. It’s not the typical memorization to get the marks they need on that test or to get into university; this is skill-based, where they’re going to learn the skills they need for lifelong learning.” Even there, when Bissonette mentions lifelong learning skills, there’s a sense she’s talking about something much more than just, say, good note-taking or time management. She’s referring to the posture the learner takes with the world around them, the qualities of being open and observant, interacting with it, being curious about it, and really availing themselves of the world and the people all around. She and Vogt both talked to us about learning that is sustainable, meaning that it has those deeper connections between the content of the curriculum and the learner.

And then there’s the polar bear dip. As much as the outdoor component of learning is important, the more typical aspects of outdoor education are as well. There are trips and camp-outs, swimming, hiking, and canoeing that everyone—faculty, staff, students—all take part in. “Yes,” Bissonette says, “I have done it twice.” This, after insisting to the last head of school that, while she likes the concept, jumping in the water in winter through a hole in the ice just wasn’t for her. But then … she did it. She also leads the lighthouse swim at the end of September and May (when the water is warmer, true, but still not entirely for the faint of heart). There’s a lighthouse about 400 metres out from the main dock, and all are invited to participate. It’s an event, one that animates the life of the school. Swimmers go out together, followed by supporters and lifeguards in canoes.

“My 10th grade history teacher, for a unit on archaeology, buried things on campus in a designated area and actually taught us proper technique for a dig. It was amazing.”

—Jenny Spring, ‘05 alumnus

Graeme Smith is the outdoor education lead, which would be a secondary role in most schools. Here, it’s central to the academic program, as well as the co-curricular offerings. Were you to visit on a typical day, you might see him leading survival classes, shelter building, or fire lighting. Then again, he may be teaching wilderness first aid, or canoeing, kayaking, or even swimming. When there’s snow on the ground, he might be out with a group cross-country skiing or building quinzhees.

When we ask Smith why parents should find any of this important—fire lighting, for example, is not something students will be including on their university applications—a spark appears in his eyes. “Have you ever seen a kid light a fire without using matches?” he says. “Using flint and steel?! It’s one of my favourite things in the world.” He compares it to seeing a child catch a fish for the first time. “It’s just a sense of accomplishment, a sense of, ‘I didn’t think I could do it. But now I can.’”

For most schools, outdoor education is a trip at the beginning or end of the year. At Rosseau Lake, it’s about that: showing kids that, whatever it is, they can do it. “I always talk about the transfer of learning,” says Smith. “That you can learn these hard skills and apply them to a really concrete, tangible task or outcome.”

There are trips, of course. Students are required to go on three a year. Not all students relish the thought, at least, not at first. Some arrive never having been in a canoe, never having swum in a lake. Tia Saley told us about a girl from China who had never been in a canoe before and, soon after arriving—literally days—she was out on a canoe trip. “She said when she came back and got to eat in the dining hall, she was so thankful for that,” Saley says, chuckling a bit as she does. “And when she got to have a shower, she was so thankful for that. Through the mere act of taking away those luxuries, she said it was the biggest triumph for her, ever, to finish that canoe trip. She was so proud of herself to have pushed her comfort zone and to have done something new. And then to be able to come back and share that experience, and appreciate the things we have at our fingertips—I think that shows a lot of growth and personal learning.” And, with the next canoe trip, she was first in line to do it all again.

It’s a lot, but staff is aware and ensure that, whatever the students’ familiarity, the trips are never onerous. They are also keen to really underscore a sense of accomplishment, which is considerable. If a child starts in Grade 7, by the time they graduate, they will have spent in excess of 50 nights out on trips. There’s one major outtrip every fall when the entire school is out for five days. Many of the academic courses also implement outtrips in the programming. “I think it would be safe to say that the students sleep out in the winter and in the springtime as well, every year,” says Smith. Because there are optional weekend trips, some students push it well beyond that, taking as many trips as they are able. In winter, students build quinzhees out of snow and, while entirely optional, most spend a night in one.

The challenges are physical, to some degree, though there’s a lot of joy as well. “A well-rounded life outside will give you that,” says Smith. Of the trips, he says, “I hope students take on the passion of wanting to spread that joy to others. The things I’m teaching them, they could potentially teach their children, or nieces and nephews, in the future.” Environmental stewardship is part of it, too, as is an appreciation of mentorship, both receiving and giving. “That’s my biggest goal,” Smith says. “Just to create a group of kids who love spending time outside and love teaching what they know to others.”

When we ask Bissonette to describe a typical student, she says it’s one “who is willing to give interest, to take some risks, to think outside the box, to be willing to sleep outside under the stars,” adding, “that adventurous spirit.” She admits that not all arrive with it, but that, taking cues from others, “it’s not hard for them to realize they want to be a part of that.”

“It’s a lifestyle,” says Smith. “Outdoor education isn’t separate from education or environmental education. It’s all interwoven.” There’s education in the outdoors and there’s education for the outdoors, and they’re both related. It includes everything from reading under a tree to mastering survival skills. The lasting lessons are many, the foremost being a sense of what accomplishment feels like. “You learn all these soft skills—sense of accomplishment, the fact that you can.” Students build a feeling of efficacy within themselves, that they can learn skills and postures—curiosity, humility, resiliency—and apply them to a range of challenges. “Even things like knot tying,” says Smith. “A lot of kids struggle with the tactile process of tying a knot. But once they learn a couple and realize the applications, it’s really simple stuff, but it becomes really important and useful to them.” Again, the lessons go well beyond merely tying knots.

Seven Generations

There are so many things that mark Rosseau Lake as innovative, and Seven Generations is one of them. The program is grounded partially in place and the awareness of the First Nations communities for which the region is home. What makes the program distinctive is that it doesn’t begin and end with the expression of gratitude, the land acknowledgement, at the start of each day. Far from it. It’s an active engagement with the local First Nations, which includes formal academic partnerships. Through them, the school works intently to integrate indigegogy, Indigenous ways of knowing and teaching, into the curriculum. A primary intention is also to ensure First Nations students access the school, particularly those from communities within the Parry Sound and Muskoka region.

It’s not uncommon for schools to include Indigenous knowledge and history within the curricula. What’s uncommon here is how it’s done and why. “Most of the way they see Indigenous people is all deficit-based,” says Kory Snache-Giniw of typical non-Indigenous students. “Within the media, within education, it’s always a negative focus. We highlight what’s great about communities, and what’s great about Indigenous contributions in all aspects of life.” Rather than positing us and them, it’s about us. Rather than an historical discussion, it’s about how history informs our experience in the here and now. By the time they graduate, students of RLC will have met with elders, learned aspects of Indigenous knowledge and history, and lived and worked alongside members of First Nations communities, just as they have lived and worked alongside students from other cultural communities. It’s hard to overstate how important that is. While other schools may intend for their students to appreciate these heritages (and any effort there, it should be said, is a good effort), too often there isn’t a sense that we’re all walking together and all represent living, breathing, vital aspects of Canadian life.

The formal mechanism for committing to those various outcomes, the Seven Generations program, was launched in 2016. Kory Snache-Giniw is the Seven Generations lead and a member of the Anishnaabeg community of Rama First Nation. “It refers to an Indigenous understanding of decision-making,” he says of the program’s title. “[Where] people look at seven generations ahead and seven generations in the past before they make any major decision.”

Snache-Giniw first came to Rosseau Lake through a position with Outward Bound Canada. He was seconded in order to offer professional development around cultural competency in teaching students from Indigenous communities. That quickly grew to include the integration of Indigenous perspectives within the core curriculum. Now on faculty, he does all that and more, including language instruction. He sees the benefit of the initiative to non-Indigenous students as a more inclusive outlook and having ways of incorporating inclusive practices into personal and professional life. “Understanding that not everything is one way,” he says, “that there are circumstances they need to consider when working with other groups, culturally, systemically.” Key is an awareness that not everyone has equal access to elements of civic life, that everyone faces different barriers to success, and then understanding why that is. Snache-Giniw also feels there is beauty in other perspectives and other ways of knowing.

Athletics

Sports are mandatory for all students between 3:30 p.m. and 4:30 p.m., and there’s a variety to pick from throughout the school year. Given the size of the school, the success of the varsity teams is surprising. Says an alum, “It just shows that Rosseau is able to encourage students who maybe have never played that sport before to join the team and try something new.” There are more varsity teams than perhaps you’d expect to find, and they compete with schools throughout southern Ontario. The field hockey has won many competitions many times. The ultimate rugby team, too, is very prominent in competition.

The school doesn’t have a full complement of sports facilities, as you might find at an urban school. The gym is small, for one. It’s beneath the dining hall and lovingly referred to as the Dungeon. (It’s actually bright and inviting, but more a space for weight training than, say, basketball.) They make good use of local resources beyond the campus. There are opportunities for competition, though there is a focus, too, on accomplishment, active living, and healthy lifestyles.

One of the athletic highlights of the year is the Hekkla, an 18-kilometre run, walk, and jog or a 28-kilometre bike ride. It’s been mounted every year since the school was founded. The culmination is a steak dinner, and for those who complete the run within a prescribed time, there’s lobster, too. It’s a considerable challenge, but there’s also that piece of showing yourself that you can do it. And it’s teamwork. (Bissonette recalls a moment a few years ago when a young boy was nearing the finish line and fell down. A senior student stopped, put his arm around the boy, and stayed with him until the end.) When they gather for dinner, there are spirit awards that are an opportunity for students to tell stories of what they saw and what was special to them. For that, and much else, the Hekkla is invariably reported as unforgettable. A more recent addition, smaller Hekklas—delightfully called Hekklets—are mounted by alumni in Hamilton, Toronto, and internationally in London, Tokyo and elsewhere.

Co-curricular activities

Throughout the school, it seems the legacy of Kurt Hahn is never all that far away. That’s true in the co-curricular offerings as well, of which Round Square, founded by Hahn, is a key aspect. Tia Saley, Round Square coordinator, describes it as the school version of Outward Bound. It’s based on six pillars, which are called the Ideals: International Understanding, Democracy, Environmental Stewardship, Adventure, Leadership, and Service. Saley has worked with Round Square in various capacities over the past two decades, including a position on staff at Round Square leading trips in northern India. More than 200 schools participate, and there are various opportunities for students to experience different cultures, including immersive ones, for which they travel to take part in international service projects. International conferences bring together students from around the world to work toward some common goals. “This year, they’ve been virtual” —we reached Saley during one of the pandemic lockdowns—“but it’s been pretty neat, when travel has been so limited, to have a different group of people from around the world to talk about the same things.” That included all the many kinds of lockdowns. “Some of our senior boys joined in a women’s forum and got to meet with 70 other students and talk about different women’s issues that exist around the world.”

In more typical times, Saley is dedicated to developing and planning cultural exchanges between schools. In 2019, that included exchanges with schools in South Africa, Australia, and Romania. Rosseau Lake College also sent a delegation to a conference in India, where the theme was “The World We Wish to See,” and it coincided with the anniversary of Gandhi’s birthday. “They had artificial intelligence come. Her name was Sophia—she was a robot—and she did the presentation and answered questions,” Saley says. The opening speaker was Kailash Satyarthi, a child’s rights activist who was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 2014. There was a performance artist, an electronic music producer. On the final day of the conference, participants took part in a three-kilometre run alongside Major D.P. Singh, a retired officer of the Indian Army and a war veteran known as India’s first blade runner, as he runs on prosthetic legs.

“In our own school, we’re bringing those kinds of things in,” says Saley, talking about internationalism, service, and global citizenship. One means is through theme weeks. When we spoke, the school had just completed Earth Week. Every student in the school is also part of a committee organized by the Round Square prefect, a student leadership role. That prefect oversees, for example, Multi-Cultural Week, organizing students around a series of events. There’s an adventure component as well. “Last year, we went up into the mountains, into the foothills, which was beautiful. And then we did whitewater rafting on the Ganges. So there are some pretty memorable things you get to do as part of the experience,” Saley says. While the school is in a rural setting, the Round Square program provides a window onto the world. “We’re in this peaceful, beautiful calm,” she says, “but then we get to have this flavour of all these other things as well.”

Student population

“I wasn’t your typical learner,” says Jenny Spring, who grew up in Huntsville, Ontario, and graduated from RLC in 2005. “I don’t enjoy sitting in a classroom. I found Rosseau Lake College way more engaging. The small classes and the emphasis on outdoor education really helped me focus more on my education and helped me get into university.”

Those are the kinds of stories you typically hear when speaking with students and alumni. They turned to Rosseau Lake because they wanted something more. “I didn’t feel like I’d grown up yet,” says student Nils Deiter, who arrived from Germany. “I wanted to use RLC as a gap year, to grow up a bit and … to be a child a bit longer.” He describes enrolling as “the best decision I had made so far in my life.” He explains, “I went there with the idea to be a totally new person. I think I’m a different person when I am here. And I think I am a better person when I am here.”

The student population is evenly split between international and domestic students, and is divided into four houses: Perry, Ditchburn, Kawandag, and Eaton. Day students come from Port Carling, Huntsville, Bracebridge, Gravenhurst, Parry Sound and others from closer by, including Rosseau itself.

The boarding community is notably diverse, particularly given a student population of this size. In any given year there are typically around 20 different nations represented—from Austria to the Cayman Islands—within a boarding community of slightly more than 75 students. About 25% of the boarders take weekend leave, which, of course, means a majority stay. Weekends are a mix of activity and downtime.

It’s a small school, which has benefits and, for some students, drawbacks, too. “The challenge of the circle is there’s nowhere to go,” says Vogt, in reference to the school community. “That can be hard for certain people. There’s no one to hide behind.” Yes, it’s not for everyone. While the varsity offerings are impressive given the size of the school, it’s also true that this isn’t perhaps the right place for those particularly invested in, say, elite basketball.

Most students who attend, however, are attracted in part by the size, the close-knit feel, and the fact that the school is located outside a large urban centre. “It is pretty small,” a Grade 9 student told us, “but I find small kind of works for it.” She feels it’s more fun, with more interaction with teachers and stronger relationships with peers. All the students we spoke with also appreciate living and learning with a relatively small cohort of like-minded people. Many talk about the school feeling like a family, though you begin to see what they’re really referring to is connection. This is the place where they started meeting people they could really talk to. The classes are great and fun and important. But the most important places in their lives are the dining hall, the residences, and the lakefront—in short, the places where people gather in small groups to sit and talk.

The students clearly understand the school is unique, and they appreciate the opportunities it offers. “She knows she’s lucky to have it,” a parent told us. It would be easy to assume that all the students are drawn by the sense of adventure and share an adventurous spirit, though that’s not the case. Yes, there are kids who attend precisely because outdoor education is their element, yet most are attracted simply because they need something different and more traditional academic settings aren’t the right fit.

Parents & alumni

Parents comment regularly on the strength of the Rosseau Lake community. “I really believe all of that has fostered Zoe’s individuality,” a parent told us, “and has taught her to think independently.” One told us, in light of the range of mentorship relationships, that he has been impressed with the kinds of ones his son has forged with other students during his three years at the school. “There’s nothing better than a mentor your own age.”

Another parent described the school to us as “supportive, friendly, and fair.” The character education, too, features largely in all the discussions we had with parents, many citing the school’s ability to foster independence, resiliency, and confidence in the students’ abilities: “The school nurtures the students’ creativity, but [it] also thinks of ways to best utilize what they’re given.”

The move to online education at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic is often cited as an example of RLC’s agility. “The school didn’t miss a beat,” a parent told us. “They took maybe a day off.” Online classes were up and running the day after that. “They were able to just jump back in and say, ‘We can do this.’ I was really impressed by that.”

Communication is characterized as exceptionally open, and parents feel a part of the life of the school, knowing they are free to be involved. Most are remote from the school, but those nearby are welcome to participate in events, such as the annual work weekend. Parents comment on the sense of service and the ability to think independently that students gain. Says a parent, “Rosseau Lake gave him the opportunity to be the best he could be, in all fields.”

Pastoral care

“We are with the kids 24-7,” says Bissonette, “or at least in their waking hours.” Many of the faculty live on campus. Each is on a house parent team and has one day and night shift every week when they are directly responsible for the kids in their house. They coach. They offer clubs. They eat meals together, sharing the tables in the dining hall. “We get to know them not just as students but as people as well,” Bissonette says. They see them in the classroom, but they see more than that, too. “Students aren’t always the same in the classroom as they are out on the sports field or as they are singing and dancing and cheering outside, and being their true selves. We’re a part of all that.”

Part of Bissonette’s project when she first came to the school was to create a counselling program that would blur the lines between the counselling office and the student population. The head wanted to ensure counselling wasn’t just the thing over there that the kids would go to only when they needed it or accessed only by appointment or referral. What attracted him to her plan was that it would be everywhere, all the time. “We could sit at a picnic table, we could sit on a rock, we could go for a walk around the property,” she says. That’s what he wanted counselling, and the counselling relationship, to look like. “We have enormous opportunities because the students board … the gift of time … the important experiences they have when they’re not in class.”

All the students are greeted outside the dining hall each day as they go into assembly. Teachers shake their hands. “They look me in the eye,” says Bissonette, “and I can tell by them looking in my eyes how their day is and how they’re doing.” That kind of interaction is something she’s worked to develop during her time at the school. “At first, it was just the head and assistant head who greeted students each morning,” she says, though it slowly grew. On a typical day today, a majority of the teachers are there. They then move together into the dining hall, and the entire school population stands in a circle. They sing a national anthem—sometimes Canada’s, other times, one from one of the students’ home countries. “We’re very big on expressing gratitude.” Then there are announcements. “There is no hierarchy,” Bissonette says, as one person says what they need to and then another, maybe in the style of a Quaker meeting house, were they to think of it that way. “It just reinforces that aspect of community.” The students then go on to their classrooms, and the day is begun.

It’s not the typical approach to social, emotional, and academic counselling, though that’s perhaps why it works so well. There are, of course, formal structures within the counselling program, the most visible being that students meet with faculty mentors twice a week, one of the highest frequencies of that kind of thing we’ve seen. Academic counselling follows a fairly strict schedule, with students and alum reporting that they had post-secondary applications in well ahead of time, which means all that goes into them—selection, research—happens well ahead of time, too.

All Grade 12 students are asked to deliver a community talk, which is equal parts reflection—they talk about how they’ve grown, what they’ve learned, experiences they’ve had, and relationships they’ve formed—and thanks. Some talk about the teachers who have helped them along the way. They might discuss some aspect of their life circumstances or challenges they’ve faced in their lives. Some compare the differences they’ve seen in themselves from the moment they arrived on campus and the person they’ve become. Community talks are delivered in the morning circle, and from January on there are about two every week until the end of the year. The talks are cathartic and emotional, though they also serve to galvanize the community. Students reflect on who they are, how far they’ve come, and where they’re going. That the entire school—all grades, all faculty— is an audience for the talks means they provide a unique reflection for all, a time to think about some big, important ideas about who we are in the world. They aren’t an aspect of the wellness program, though they clearly have an important wellness function.

The takeaway

Rosseau Lake is a small school—the student population, including both boarding and day students, sits at 110. Located on a lake in Muskoka, it offers a lot to get excited about. It’s intimate and active, and the physical plan is stunning. The school recently used its 50th anniversary year to renew its commitment to providing a very personalized, forward-looking educational experience.

Throughout its life, Rosseau Lake has forged its own path, its own tradition, which itself is a primary draw for students and faculty alike. It’s true that every school is unique, though that’s especially true here. In so many ways, it’s one of a kind, beginning with the integration of outdoor education into all aspects of student life. The Seven Generations program, too, is a model for others to follow. And on it goes. The students come because they want an education, yes, but also because they are looking for more. They want to be engaged, to find a place within a community of kindred spirits. They intend to go on to post-secondary studies, though they also understand that school should never be only a stepping stone to some future accomplishment. The school rightly prides itself on graduating students who have a strong sense of identity as learners, are able to describe who they are, and analyze the experiences they’ve had. And while many schools will say those kinds of things, Rosseau Lake can actually point to them. In addition to earning a degree, students leave having spent the equivalent of two months on outtrips. They’ll have paddled canoes, tied knots, and, for many, travelled the world. Despite the small size of the school and its location beyond urban centres, they will also have learned alongside others from diverse communities around the world and down the street. As alumni invariably say, they will have also gained a profound sense of community, having experienced how important they can be to a group, just as they’ve been lifted by it. Both Vogt and Bissonette noted to us that Rosseau Lake may not be “the school for everyone,” but, in many ways, perhaps it should be.