St. John's-Kilmarnock School THE OUR KIDS REVIEW

The 50-page review of St. John's-Kilmarnock School, published as a book (in print and online), is part of our series of in-depth accounts of Canada's leading private schools. Insights were garnered by Our Kids editor visiting the school and interviewing students, parents, faculty and administrators.

Our Kids editor speaks about St. John's-Kilmarnock School

Basics

SJK is a small learning community by design, where strong relationships are fostered and contribute to the overall student experience. Both curricular and co-curricular programming provides opportunities for students in Junior Kindergarten - Grade 12 to collaborate, learn, and play together. Students, teachers, and staff know each other not only by name but also importantly by their individual passions and pursuits. This level of personal understanding enhances the shared experience and broadens the depth of the learning journey. The result is a connected community where big ideas and a global perspective live.

“Academic excellence is foundational to who we are,” says Cheryl Boughton, Head of School. The school’s strong commitment to the International Baccalaureate (IB) Programme across the school, a program that is academically rigorous while also embracing arts and service, is an expression of the school’s ideals. SJK offers the IB Primary Years Programme (PYP) for students in Junior Kindergarten through Grade 6, the IB Middle Years Programme (MYP) for students in Grades 7 to 10, and the IB Diploma Programme for students in Grades 11 and 12.

“We are constantly challenging our students to be the best version of themselves,” says Boughton. “Our graduates are well-rounded, and we want them to go out and have an impact in the world.”

Authentic relationships are at the heart of the SJK community. At SJK, people are known and valued in a community where all members have a voice. Students, teachers and staff, parents, alumni, and its community partners all contribute to the vibrant and diverse learning environment at the school. Fundamentally, SJK believes in the power of developmental relationships and that students learn best when engaged in purposeful, healthy relationships between teachers and young people.

Today, SJK includes a Lower School, comprising Junior Kindergarten through Grade 6, and an Upper School, comprising Grades 7 through 12. At all levels, the school offers a small learning community by design, where strong relationships are fostered and contribute to the overall student experience. Both curricular and co-curricular programming provide opportunities for its youngest and oldest students to collaborate, learn, and play together.

The school grew and developed considerably over the years, now occupying a property that was acquired in 1988. It was a blank slate—there were no buildings of any significance on the site when it was purchased—and therefore the facilities have been constructed entirely to meet the needs of the SJK program in general and the IB specifically.

Development completed in 2016 affected the entire campus. The addition of a new building called “Newton House” added a unique focal point for school life, one that includes a dining hall, a meeting space, and a learning commons. The outdoor play spaces, too, reflect the culture and growth of the school, including the addition of a boathouse for environmental education activities.

In March of 2023, SJK began adding a new art and design media centre to its campus, bringing together all the school’s multifaceted creative programs, including media production, visual arts, and design of all kinds. It was set to open in the fall of 2023.

All of the additions carried out over the years since the school’s move to its current location have been wisely integrated with existing facilities, and visitors would be hard-pressed to find the divisions between the old and the new. Throughout, the presentation is crisp, modern, seamless, and up-to-date.

“We are constantly challenging our students to be the best version of themselves. We want our students to graduate very well rounded, and we want them to go out and have an impact in the world.” —Cheryl Boughton, Head of School

The school’s rural location was chosen not only for what it offered in terms of space, but also for its proximity to the communities that the school was serving, several of which are within a 20- to 30-minute drive. As such, the school is transportation dependent.

“We have bussing from Cambridge, Kitchener-Waterloo, Guelph and Elora,” says Britt Leeking, Director of Enrolment. Students need to live within those cities or near enough to get to a bus stop. “A number of our families rely on school-provided transportation,” says Leeking, “while others drive their children.” The semi-rural setting offers welcome exposure to nature for children who come from city or suburban neighbourhoods. “We feel fortunate to have the unspoilt forest area,” says Karen Baird, Assistant Head of School. “The outdoor [experiential] education teacher takes them out there to play and learn.”

Leadership

The current Head of School is Cheryl Boughton, who assumed the role in 2019. Prior to that, she’d been at Elmwood School in Ottawa for more than a decade, and before that she had worked for four different independent schools in the UK.

“It was too good to pass up,” says Boughton. “I had learned leadership skills, and I had learned in a variety of schools. I think of myself as a transformational leader. I saw a job open up here and I said to myself: Okay, here is a good school, and let’s make it even better.”

Boughton arrived just in time to help the school find its way through a global pandemic. Her experience as a change leader meant she was able to help faculty and students cope with how the pandemic affected learning environments during 2020 and 2021, and then how everything changed again once after public health restrictions were lifted in 2022.

“One of the things that I’m committed to is environmental sustainability,” says Boughton. “I’ve been committed to that my whole career.” Advancing sustainability practices was difficult during the pandemic, she admits, but she was proud of improvements that were underway during the 2022-2023 school year. For example, the school implemented a new composting program to divert food waste from landfill.

Sustainability is an issue that’s close to the heart of students at SJK as well, and Boughton seems delighted to collaborate with them. She invites ideas and input. One recent project proposed by Grade 2 students reveals how student input is taken seriously. The students approached Boughton with an idea for a bee pollinator garden as part of their bee preservation project. They wrote the proposal and delivered it in person to her office. It was approved, and the Grade 2 students—and the bees—will soon have their garden.

Making change that sticks is about responding to feedback, says Boughton. “It’s about listening, and basing what you do on feedback that you’ve received,” she said. By listening carefully to the students, she identifies patterns of change, then tries to enhance the change that is already underway. “That’s what can make change really effective and impactful.”

David Bennett graduated from SJK in 1985 and confirms that the school is in a constant state of evolution. “[T]he school has evolved immensely. It is, quite frankly, a different school in all but name, [though] the principles of a strong community and breadth of experiences remain intact.” Bennett enrolled his children there, and is now chair of the board of governors.

The student body and faculty is divided into two schools, with Kindergarten through Grade 6 designated as the Lower School, and grades 7 through 12 the Upper School. Each has its administration, with Lower and Upper School directors filling the role of principal for each, and reporting to the Assistant Head of School.

Director of Lower School Ron Clark has a long history of working in independent schools, with 26 years as an administrator and teacher at Rundle College in Calgary before coming to SJK. If Boughton’s leadership focus is sustainability, Clark’s is connection.

“The kids are people here,” he said. “They’re not a number. I know all the kids’ names, and that’s one of the real true benefits of such a small community.” His desire to connect extends to families as well. “I do outdoor traffic duty (at drop off) because it’s a way to connect with parents. It’s a great way to be present, and that was especially so with COVID, when families couldn’t come into the building.”

The school does not have an intercom system, he noted in a phone interview with Our Kids. But for him, that lack of technology was a positive. “It makes me intentional about getting around the school to talk to staff face to face.”

For her part, Director of Upper School Jill Watson brings an international perspective, having taught in Asia for 18 years before landing at SJK. In a phone interview with Our Kids, she spoke of her enthusiastic commitment to creating well-rounded students.

Watson is particularly active in the arts program, and teaches drama to Upper School students. She also actively encourages co-curricular activities and notes that these activities are designed to help students discover possibilities.

“We have good partnership and support systems to help students to help them find their unique talents, their unique ways of getting involved,” said Watson. “We really go out of our way to make sure that every student is engaged.”

Key words for St. John's-Kilmarnock School: Activity. Creativity. Service.

Background

The idea for the school, including its academic profile, was first described at a meeting in Elora in November of 1971. Soon afterward, a board was formalized, and in September of 1972 the first classes were held within the Church of St. John the Evangelist in Elora. There was no formal association between the church and the school beyond the community that gave it a context, shared space, and shared values.

The impulse to found the school was ad hoc, and care was clearly given to ensure that it presented as organized and efficient, with all the various ducks in a row. And, in every way, they were. The Ontario Legislature passed the St. John’s School (Elora) Act on April 25, 1972, after which it was given royal assent; the school was then dedicated on November 5, 1972, by the Bishop of Niagara, the Right Reverend J.C. Bothwell.

Certainly, if you want to inspire confidence at the creation of a new school, that’s how you do it. Where some schools are created in a series of unrelated stages, St. John’s (its name for the first 12 years) had a clear mandate from the beginning, to which it has been faithful throughout its life. Then, as now, the mission was to serve the community it sat within, adding an important piece to the regional educational mosaic.

St. John’s would offer a challenging academic environment that would inspire and support students toward the values of ethical citizenship and community leadership. There has always been an association with the Anglican Church, though the intention was to use that faith tradition as a starting point, rather than an end point, underwriting the values that inform the life of the school, including respect for oneself and others.

The school is based on the Anglican model, though it is not a parochial school. Services are sometimes held in the chapel, though the feel is that of a school-wide assembly. It’s a time to celebrate the members of the school community, their accomplishments, and to underscore the foundations of the community they all share. The school quickly grew beyond the capacity of the church. A sister girl’s school, St. Margaret’s, was founded in 1976, and later, in 1981 a co-ed secondary school was opened in Waterloo. By 1985 the schools had been combined and had a shared name, St. John’s-Kilmarnock, inhabiting a number of leased buildings.

While the program was academically and socially strong, the division across the various properties created some redundancy within the overall infrastructure, and was becoming a stumbling block to a consistent delivery of the curriculum. A dedicated property would be necessary to the maintenance of the range and quality of the academic and co-curricular offerings.

The current property was purchased, a 36-acre lot in Breslau that included green space and the remnants of a quarry. That there are no traces of the quarry today is rightly a point of pride.

The campus was dedicated in 1990 by Reverend Bothwell as well as Lincoln Alexander, then the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario (and soon to be named chancellor of the University of Guelph).

“There has always been an association with the Anglican Church, though the intention was to use that faith tradition as a starting point, rather than an end point.”

“There has always been an association with the Anglican Church, though the intention was to use that faith tradition as a starting point, rather than an end point.”

Academics

As it evolves for the modern era, the school returns to its mission statement for inspiration and focus: “Our mission is to discover the unique talents of each student, ignite their love of learning, and build their capacity for global action.”

That admirable mission continues to drive development of facilities and programs, including the growth of the IB programme. The IB distinguishes SJK and is a draw for many families.

“The IB programme meant a lot to my husband and me,” said parent Meena Sharify-Funk. “We appreciate global pedagogy,” and certainly her family is not alone in that among the school’s parent population.

“All of our students are engaged with the IB diploma,” says Director of Enrolment Britt Leeking. “Because this is the only program we offer, our students share the same goals, and we’re all speaking the same language.”

The result is an opportunity to really focus all the activity of the school on the delivery of the IB, both in terms of infrastructure—spaces are tailored, for example, to the collaborative elements—as well as supporting the values that undergird it. That includes an international perspective, experiential learning, project-based instruction, and peer collaboration. “I think the IB Programme is a benefit to the school because of the way it’s taught,” says parent Jennifer Shingler, “the ideology behind it.”

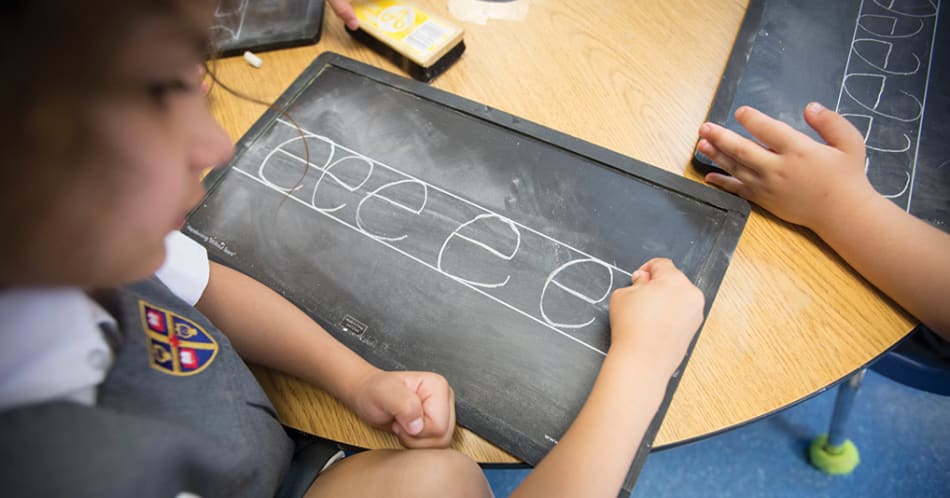

Classes are small, with an average class size of 17. Teachers work alongside students rather than lecturing from the front of the room. The school has been experimenting with classroom organization and has furnished classrooms with modular furniture that can break up into different configurations and be moved aside if necessary. Students have a range of seating options, including rocking stools, and they are free to choose among them.

Smartboards are used in the Lower School. Students from JK to Grade 3 have access to shared iPads in classrooms. Students from Grade 4 to Grade 12 bring their own devices. Devices are used within strict guidelines, one of which is that no devices are used in the dining hall during meal times.

“Our belief is that the best way to teach the fundamentals is when things are contextualized, are relevant—you can connect them to other things that make sense to you.”

In the classroom, the fundamentals are a focus, but teachers work hard to adapt the curriculum for a diverse, modern student body.

Chair of Arts David Newman explains: “Our belief is that the best way to teach the fundamentals is when things are contextualized, are relevant—you can connect them to other things that make sense to you—and so that really underlies that IB philosophy.”

Behind the fundamentals, for Newman, is understanding the process of thinking that goes into them. “You’re not just being taught how to read and write, add and subtract. You’re also being taught how to think about those things.”

Everything is a balance, and the program at SJK has navigated it particularly well. Students aren’t required to parse sentences, say, but they do need to know the basics and be able to apply them. There are big ideas, too. Theory of Knowledge is a required course, per the IB curriculum, for all students in the diploma programme. It’s a philosophical underpinning for courses in other subject areas and students are expected to make connections.

It’s perhaps easy to see that academically inclined students will thrive at SJK, though there is a demonstrated attention to a broader spectrum of learners. While the focus on academic rigour has not lessened, the school continues to expand its holistic approach to education, said Boughton.

For example, during the pandemic, a greater emphasis was placed on outdoor learning for the younger grades, she explained. In the Upper School, “Our kids were learning how to cross country ski. There was a walking group, and snowshoeing. There were definite times where it was better if they could be outside connecting with each other, breathing fresh air.”

The school’s spacious campus allowed classes to thrive even during the most restricted periods, said Boughon. That caused families to spread the word about SJK. A number of new SJK families found the school during and after the worst of the pandemic. “School just became more important for a lot of families,” said Boughton. And some new families found the school after moving to the area from larger cities during the pandemic exodus from big cities to smaller cities and towns.

“I don’t think we needed to do the same sort of recovery that other organizations did. We’re really growing,” says Boughton. “There is so much interest in our school. But how do you balance that growth with who you are? We could expand very quickly but we would lose important elements of who we are. So we are growing intentionally and sustainably.”

Underway in 2023, a renovation of a new multi-functional space for art and design programs will develop the school’s offerings. Teachers of creative subjects had been working in spaces that were spread out throughout the campus. The school decided to bring everything together into one space in a previously underused space beneath the school’s chapel. It had been underused, and seemed an appropriate space that could be reclaimed for creative pursuits.

“We’ve always had a strong design program,” says Boughton. “Teachers have been working in facilities that were good, but we wanted to give them spaces that were more conducive to what they’re doing.”

As the school was getting underway with the renovation in March, 2023, Boughton described the vision. “We’ll have a dedicated visual arts room, with different zones for different types of media,” she said. “They’ll be working with a wet area for clay, and a section for digital art. You have to have the space and equipment coupled with that. There is a gallery, where we can show the students’ artwork.”

Boughton is proud of how the infrastructual developments came from a collaboration with the school’s community. She recounted how the vision came together with help from a committee that included three faculty representatives.

Jory Breen was one of three teachers who helped envision the arts and design space. As a teacher of English Literature and Theory of Knowledge, Breen sees how a creative centre for the school will benefit all its students.

“Even if you’re not going into an artistic field, having creative opportunities is so important. That’s going to make more well-rounded students. Even for those highly academic students, having some time to think outside the box, that’s to everyone’s benefit.”

A focus on the whole child

The IB programme, particularly at the diploma level, is often perceived as an elite academic program, and it is. But SJK strives to create a balanced approach to academic rigour.

As one example of how that looks, students sometimes go outside to do their academic work, says Boughton. “Yesterday, I looked out and there was a science class measuring things outside. I thought, that looks like a great lesson. And not long after that, I saw them coming back. They were all rosy-cheeked, and they were really engaged.”

Though many students choose science, technology, engineering, math and business paths after graduation, Boughton herself considers a general arts education to be excellent preparation for the future. Academic diversity is celebrated, she says, pointing to SJK’s school song, “Become the Greatest” as an example of how each student is encouraged to find their own route to success.

With words and melody by SJK music teacher Andrew Craig, the song premiered in the fall of 2022 as part of the school’s 50th anniversary celebrations. It expresses the essence of what it’s like to be a student at St. John’s-Kilmarnock.

“There’s a line that goes: ‘I’m proud to be part of a community that will always feel like family,’” says Boughton. “And then it goes: ‘Here I feel the freedom to be me,’ ” she says, laughing when she admits that the song’s sentiment sometimes brings her and others to tears at school celebrations.

Teaching

The arts really seem to matter to the SJK community. It’s one of the ways the school reaches out to its surrounding communities.

“I practice what I do,” says Catherine Paleczny, art instructor for the Upper School. She has studied in Calgary, Michigan, Japan, and Australia, and has been artist in residence at the Banff Centre, the International Ceramic Center in Denmark, the International Ceramic Sculpture Symposium in Poland, and the Experimental Sculpture Factory in China.

Not only are Paleczny’s artworks found in collections around the world, and in various public locations around the K-W area. Students can interact with her work in their local environment.

That might seem unique—it’s true that most high school teachers are not also practicing in their fields of expertise—though it’s actually somewhat typical of the hiring practices at SJK. The school takes pride in retaining faculty that are active beyond their work within the school.

For example, music teacher Andrew Craig worked as a national broadcaster for the CBC for nearly a decade, in addition to hosting high-profile events for organizations such as the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the Glenn Gould Foundation. He is also the founder of Culchahworks Arts Collective, which shines light on stories of impact made by Canadians of African and Caribbean descent.

In addition to being involved in unique ways in the community, many teachers on the SJK faculty arrive with international experience on their résumés. They can provide a global view of the world to students because they have lived globally.

SJK’s approach to hiring faculty adds authenticity to the student experience. “They are very engaged in what they teach,” says parent Jennifer Shingler. “They believe in it. I have yet to have a teacher that isn’t interested in what they’re teaching.”

And the teachers seem to relish the mandate to be involved in the community. “That ability to be involved in things outside the school does give you something back,” says Newman. “Part of our belief is that being involved yourself informs the work that you do and the approach that you have with students.”

Students grow into an awareness of the kinds of things that people do through a relationship with people who actually do them, he added. “There’s a level of credibility, and that sense that people actually do this outside of school. It isn’t just something that you learn in a classroom.”

Faculty development

The school’s leadership is aware that professional development can mean different things to different people. Most obviously, those who have been teaching for decades have different requirements than those new to the faculty. While newer teachers take part in general professional development, more seasoned teachers are encouraged to develop higher-order thinking and teaching strategies, including workshops and courses specific to their personal areas of interest. The intention is to bring authentic experiences and expertise into the classroom.

Indeed, it’s that aspect of the school that attracted Baird to SJK. She started as an elementary teacher and has been at the school for 18 years. “I loved the fact that we were given a certain amount of autonomy about what we taught and how we taught it. And we’re given a huge amount of support from our faculty and from our families too. Which just brings back the joy to the teaching.”

She and other faculty have found a welcome flexibility in what they’re able to offer students, informed particularly—at least in Baird’s case—by previous teaching experiences in the public system. “Every year in grade 3, you taught this, and every year in grade 4 you taught that … At this school we’re able to think more conceptually. We’re able to say ‘let’s take this and this and put it together because that makes sense—it’s a big enduring understanding—and it gives us more flexibility to shuffle things around.”

The outcomes of the provincial curriculum are certainly met and exceeded, though they are met in different ways and, at times, at a different schedule or pace. French instruction, for example, begins at SJK in junior kindergarten, rather than grade 4 per the provincial curriculum. Therefore, “we can’t follow those grade 4 expectations in grade 4,” explained Baird, “so we shift them down and we do them in much earlier grades, because that’s when our students are doing them. … We love the fact that we can do what we need to do, and more.”

That’s emblematic of the IB programme, though also of the ways that SJK chooses to promote it. Says Baird: “The content has to be conceptualized, but what we do is we start with the conceptual piece, and the content and the skills pieces fit into that. You can’t have one without the other: you can’t teach conceptually without having something real and meaty to get your hands into.”

Individualized learning

A signature of the SJK approach is a personalized learning experience, says Jill Watson, Director of the Upper School. “What makes the school unique is the individualized focus and attention that we give to students and their families,” says Watson. “The school goes above and beyond in making sure students are happy, that they are getting the support they need.”

Each of the IB programmes ends in a culminating project, presented at an Exhibition, which students work on over the course of their final year within each programme. “It’s totally student-driven,” said Carey Gallagher, Assistant Director of Upper School, who was overseeing the setup of the exhibition when Our Kids visited the library.

The projects require students to follow their curiosity, said Gallagher. “They figure out what their passions are, and we develop their lines of inquiry, questions. They’ve been off campus visiting places and talking to experts. A group went to the humane society. We have a group looking at brain health, so they’ve been to SHIFT, which is a concussion clinic. We have a group that went to 10,000 Villages and a fair trade coffee shop. One group connected on a Skype call with the Vancouver Aquarium to talk about animals in captivity.”

They’re big topics. Child labour, animal cruelty, consumerism, environmental impacts. The intention is to develop the students’ curiosities and interests, empowering them to contribute to a solution within their communities, and to develop leadership opportunities within the school.

The school supports the projects in a range of significant, and often surprising ways. One group chose to live a day animal-free, during which they worked with the kitchen staff to develop and prepare vegan meal options. “Tomorrow’s the big day,” says Gallagher, “they’re just putting their displays together. They had to do creative pieces. Some of them have written songs, created pieces of artwork. We give them the framework and off they go.”

One of the students was presenting on rock music, and during the setup was practicing classic, heavy-metal licks on an electric guitar. His talent was clear. So was the fact that his interest was taken seriously, and he was supported in using that as a way into a project around music and culture.

“I just found AC/DC and I went from there,” he said. It was as lovely as it was impressive; teachers are clearly keen to meet students wherever they are.

“That’s one of the things that I like about the school: there’s more of an opportunity to impart your personal flair to what it is you’re contributing. Your own passion.” —Leanne Dietrich, Director of Athletics

Creative Arts Programming

Alongside a strong focus on academics and STEM oriented subjects, SJK takes the arts seriously. From the early years until graduation, students have opportunities to participate in visual arts, music, dance and theatre arts programs, both through curricular and co-curricular activities.

Students begin learning music in the early years, first with Orff instruments and rhythm-based movement activities. They begin playing instruments in grade 4. Since the school’s inception, choral music has always been a foundation of the music program, and that focus continues today. Students perform at the school and in the community in such events as the annual Conference of Independent Schools Music Festival (CISMF) at Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto.

When it comes to theatre, SJK embraces its location in southwestern Ontario by engaging with professionals at the renowned Stratford Festival. Beginning in grade 4, students see a production at Stratford every year and experience workshops related to the play.

For example, in 2023, Grade 4 and 5 students attended the Stratford production of Little Women. Other grades have also attended plays, and the school’s drama students went to Stratford to attend a week-long annual drama event known as the CIS Drama Festival. Hosted by the theatre and arranged through the Conference of Independent Schools of Ontario, the festival is a chance for student actors to work with Stratford company members and perform on one of Canada’s most renowned theatrical stages. The students also do an annual theatrical performance. The 2023 show was The Laramie Project, a play that has been part of a grassroots movement against homophobia. As Chair of Arts David Newman described in his director’s note about the play, it was a dramatic and technical test for students, but they rose to the challenge.

Outdoor programming

Outdoor education is focused around the boathouse, the pond, and the forests. The pond is used for outdoor studies in the fall and spring, including a 24-hour pond study for the Grade 7 class. Students camp out overnight.

In winter, the pond is maintained as a skating rink. An adjacent green space provides opportunities for instruction and recreation, including a maple project each year. At graduation, the grade 12 class celebrates by jumping into the pond.

One positive change that emerged from the pandemic era was that the school invested in creating a functional outdoor classroom. To accommodate a greater desire for outdoor learning, SJK built a beautiful outdoor classroom with a living roof. It has no walls, and is nestled in forest located on the school’s 36-acre campus. Benches convert to tables to allow for flexibility in use of the outdoor space.

Community involvement

Assistant Head of School Karen Baird describes how the school creates interactions between the school and its surrounding communities. The goal is to reach a bit further than whatever the curricula might allow. “What kinds of things can we bring to our classrooms every day that will help our students learn and grow? “We have people come in to talk about what it’s like to do different kinds of work in the community, whether it’s a parent or grandparent. And we try to build partnerships with universities in the area. Some of our teachers teach at Wilfrid Laurier University, for example. And some of the (student) teachers there come here to learn about being teachers by doing a practicum. We are trying to build partnerships with universities and local businesses because it expands the opportunities for students.”

Faculty are supported to explore their personal interests, and challenged to find community resources that can expand upon classroom learning. Says Baird: “We’re trying to bridge out … [to] community fellowships or connections where teachers can go to a business or a factory and learn about, maybe, idea generation, or design processes [and so on] and how they work in the real world.” She admits that, within any school, there can be a sense of isolation. “We want to break out of that silo and go and explore what’s really happening in the world, and then bring that back to our students.”

Such outreach can lead to projects that connect students to service opportunities in the local community. For example, as part of their Grade 9 design class, groups of students spent time at St. John’s Kitchen, a Kitchener-based organization that helps people who are at risk of homelessness. The students prepared and served meals, put together first aid kids, and sorted and organized a donation room.

Another group of students visited the Grand River Regional Cancer Centre, a local cancer center that looks after 300 people each day with screening programs, chemo and radiation treatments and support services. The students made care packages for patients, toured the facility to learn about cancer treatments and talked to doctors planning treatments.

Co-curricular activities and events

The size of the school, with an annual enrollment of about 480, is large enough to ensure a broad offering of curricular and co-curricular programs, yet small enough to ensure that all students are known within the school. “It’s not like a huge high school,” says Anne Huntley, an alumni parent of the school. “Everybody knows everybody.”

Academic achievement isn’t the only means of gaining social currency among the student body, though there is a shared appreciation for the value of academic work. The school has a high rate of participation in co-curriculars. Programs run for six to eight weeks and students can choose activities related to arts, academics, athletics, clubs and service.

Most programs are offered after school, usually from 3:30 to 4:30 p.m., about once per week. Athletic options range from intramural opportunities to varsity level competitive sports.

An important event in the annual calendar is Eaglemania day, a games day organized by the student council with help from the Parents’ Association. Students compete with their houses, so all age levels are integrated throughout the day.

When Newman describes it, his appreciation for the event is palpable, particularly in light of the cross-grade interaction. “You’ll see a grade 12 student with a JK on his shoulders, moving around with their team, going through all these activities. There’s a great sense of bonding and togetherness.”

There and elsewhere, Newman notes that there isn’t the kind of isolation—between the middle and upper years, or the upper and junior years—that is perhaps typical in a majority of schools across the province.

Throughout, there is an appreciation of individual voices, as well as an emphasis on the strength of diversity. A new rainbow crosswalk located on campus, which is based on the Progress Pride flag developed in 2018 by non-binary American artist and designer Daniel Quasar, makes a brilliant commitment to inclusion. According to the school’s Instagram post about the crosswalk, the redesigned flag recognizes the diversity of the LGBTQ2S+ community.

Many subtle yet persistent reminders—from meal choices in the dining hall, to the focus of the world religion course, the names of the houses, to the topics raised in chapel—quietly reinforce the diversity of the student and faculty population.

Teachers are enthusiastic about participating in co-curricular activities. For example, teacher Jory Breen expresses excitement about the school’s investment in the arts and design centre, which will provide new media-making opportunities for the school’s magazine club.

“Seeing the school invest in this new project really shows that they’re leaning into a hands-on creative vision for a school. “I’m very optimistic about that vision right now,” he says.

Student population

While SJK admits a broad range of learners, the students who do best here are those who respond well to challenges and are keen to make the most of the opportunities that the school provides. “I think our biggest goal for our son at the time was just that I never wanted him to be bored at school,” says Jennifer Shingler, and certainly he hasn’t been.

The school is very much a university prep school, and the curriculum is delivered with post-secondary education very firmly in mind. There are students with identified learning disabilities, but all are able to reach the academic program, and thrive with the level of challenge the school presents.

Teachers are communicative if they identify an area where a student needs extra help. “If I’ve ever had a concern,” says parent Anne Spruin, “they say ‘Come on in, let’s have a meeting.’ But they’re also proactive, and they come to you. With one of my children, the teacher was concerned about his fine motor skills. They put together a package of materials to help him practice writing. To me, that really showed they care.”

The school gets to know each student’s needs and goals, says Jill Watson, Director of Upper School. “Our mission is to discover the unique talents of each student, ignite their love of learning and build their capacity for global action.”

In the younger grades, getting to know students is the job of Ron Clark, Director of Lower School. He’s obviously a social person, and is enthusiastic about that part of his job. When a child has a birthday, he knows about it.

“One of the things I love to do is, I sing happy birthday to every child in the building. It’s awesome. One student said I sounded like a dying goat, but I just love it!” It’s Clark’s way of creating a personal connection with each and every student. “I want them to know they’re valued. That’s so key. I’ve always said I want them to be sad to leave and so excited to come back the next day.”

Clark also works hard to create opportunities for younger children to interact with children in the higher grades. Co-curricular activities are a good place to make those connections. For example, in dance club, senior children might teach dance to children in grades 1 to 3. Senior children may act as counsellors during after-school camp. The house system also allows for cross-grade interactions. “We’re a small school so there are those opportunities,” says Clark.

Supports are available to address learning differences, including ADHD and processing issues. More important, though, is the attention that faculty give all students, and a willingness within the culture to provide individual support.

“We aren’t seeking students for whom school is a breeze,” says Director of Enrolment Britt Leeking. “We are looking for students who are motivated to try their best and ask for help. The goal is to find a balance between academic and co-curriculars.”

Students most commonly join the school in JK, and grades 7 and 9. But they are welcome at any stage of education. The school helps each student meet the challenges that come with the IB program. “We find that the IB program motivates students to rise to the challenge,” says Leeking. “When you’re surrounded by motivated peers and teachers who are helping you achieve success, it’s easy to feel motivated and engaged and excited about learning. Our students rise to the challenge.” “We’re a small community,” says parent Jennifer Shingler. “I’ve always said to my kids that if you are misbehaving I’m going to find out. It’s been very much that kind of experience.” The result is that the students are, by and large, respectful and self-regulating.

That was the quality that Anne Spruin first noticed when she toured the school prior to enrolling her daughter. “I remember walking through the Upper School hallway,” she says. “I had my younger one in a stroller and my older one wasn’t yet in JK. And the high school students were so respectful. They moved out of the way for the stroller. They held the door for us. I didn’t have to worry about what my little ones were hearing. I don’t think you see that kind of respect in most high schools, so I was really impressed.”

The community is tight-knit despite being geographically spread out, notes Spruin. “My kids have friends in Guelph and Waterloo, but everyone makes the trek for birthday parties. The parents make an effort so the kids can have that social time,” she says.

Boarding School

In 2023, about 35 members of the Upper School population were international students who lived in a residence located in Waterloo. The boarding facility has capacity for about 50 students. “It’s right in the hub of University of Waterloo,” says Karen Baird, who is responsible for the boarding program. Students are bussed to school and back at 5pm, after co-curricular activities are wrapped up.

The residence’s location means students have access to nature during the school day, but they can be part of a vibrant local community outside of school hours. “It’s very attractive because the students aren’t in the countryside,” says Baird. “We have a dining hall, a rec room and a fitness room, so it’s all very self-contained.” Students can also access public transit from stops near the residence so they can explore the cultural mileu and have varied experiences.

Boarding opportunities start in grade 9, and a large percentage of students come from China. A few have also come from Thailand and India. Baird notes that grade 9 is a great time for international students to enter the school. “The language of instruction is English. We help them get their language up to par so they are fluent enough by grade 11 and finish up with strong English by the end of grade 12.”

Athletics

“You’ve probably heard about the bubble,” says Leanne Dietrich. Certainly, we had; the defining feature of the athletics program in the past was the athletics bubble that had initially housed the sports programs. The bubble, alas, is long gone now, replaced in 2001 by a sparkling new facility. It’s a 15,000 square foot facility that includes a double gymnasium, a combatives room that is also used as a dance studio, and a fitness centre. Students also have access to four groomed outdoor playing fields.

SJK values physical activity, as signaled by the playing fields and outdoor ed facilities that are front and centre. The staff and faculty, too, promote activity, both in their classrooms and their lives. Ian Carswell, head of guidance, is a particularly good example of that. He has represented Canada in long-distance running, and also is a member of Harvard University’s Athletic Hall of Fame, having been recognized as Harvard Athlete of the Year in his graduating year. Not all the faculty have those kinds of credentials, though they all, to varying degrees, promote physical activity and provide examples of the benefits of active lifestyles. Dietrich joined the faculty in 1998 and has served as Director of Athletics for many years.

Competition is part of the SJK sports program. The school competes with other independent schools via CISAA, particularly competing with teams from Toronto and its surrounding area. But Dietrich is a vocal proponent of the non-competitive values of activity, participation, and outdoor education. There’s a strong core of non-competitive offerings, and an equally strong promotion of overall health, something that Dietrich helps lead through her participation on the Health and Safety Committee.

The athletics participation rates are higher than those in public schools. The school reports that nearly 90 percent of the students participate in the competitive varsity program—something that reflects the school’s mandate that students are involved in a range of co-curriculars.

The school has access to a local area rink for its co-ed ice hockey club, though a rink is created on the pond each winter by the Director of Development, Andrew Duszczyszyn. It’s occasionally used for recreational skating, which is as picturesque as it sounds.

Some sports, like hockey, wrestling and cross-country running, offer co-ed athletic opportunities. Other sports create separate teams for both girls and boys. Boys soccer and girls field hockey, for example.

Field hockey is an area of focus for SJK. The program began in 1985 and has thrived ever since. Dietrich, who coaches the teams, played the sport as a student at University of Waterloo and went on to coach the varsity field hockey team at the University of Western Ontario while completing her Masters of Education.

The school offers field hockey opportunities to seasoned athletes as well as beginners, and it also offers pre-season training and a focus on nutrition. Students have travelled to the U.S. and Europe.

Pastoral care

A chapel on campus provides a place for quiet contemplation and school celebrations. Featuring soaring ceilings, stained glass windows and an exposed pipe organ, the chapel pays homage to the school’s past and its Anglican roots. Students and faculty attend a monthly service in the chapel.

This service is an opportunity for SJK to gather as a community; today’s chapel services focus on the exploration of a variety of faiths to honour the diversity of SJK’s community. Events can also be recorded and live streamed so that community members can join from remote locations when necessary.

“We have students of many different religions and people with no faith,” says Boughton. “So it’s a question of, how do we gather in the chapel in a way that is meaningful for everyone? I think people are enjoying what we’re doing because it feels welcoming and relatable to students’ lives.”

Reverend Judy Steers, in her role of School Chaplain at SJK, is responsible for the wellbeing of the students, and brings experience in working with young people to the role. She broadens the student understanding of world religions to include a multi-faith perspective.

“She goes into classrooms and shares ways to be mindful,” explains Assistant Head of School Karen Baird. “

With the Lower School, she does a spiritual wellbeing class once every three weeks. It might be deep breathing or yoga, and she also brings in spirituality.” Though the school has a foundation in the Anglican faith, students are exposed to other world religions. “We might do a reading from the Bible,” says Baird. “But we might also do one from the Qur’an, or we might do something that’s more general, just about love.”

Baird notes that students reach out to Steers when they need help. “She has a deep knowledge of working with youth, and that’s one of the reasons we find her valuable. Students trust her.”

In addition to support from Steers, students also have access to a full-time registered nurse, who is trained to respond to mental health concerns, among many other things.

The houses, as well as the daily community assemblies, further contribute to a sense of community and regular contact with peers, mentors, and faculty. In many ways, all of those things offer the front line of the program of pastoral care within the school.

Discipline, when required, is handled empathetically, swiftly, and effectively, and in line with the overall values of the school. The parents we spoke with had no reservations at all in regard to the application of disciplinary action. “The kids learn that there are rules and they are meant to be followed,” said alumni parent Anne Huntley.

“Parents speak of the strength of their children’s friendships, ones that carry over into their lives outside the school.”

“Parents speak of the strength of their children’s friendships, ones that carry over into their lives outside the school.”

Getting in

For parents involved in researching schools, several recorded webinars are available on the school’s website, offering a rich view into the life of the school.

A school visit is recommended. Prospective students are invited to shadow another student for a day, and that, as well as attendance at one of the open houses, is also a great first or second step in getting acquainted with the school.

SJK is interested in mission-appropriate students, those who are able to get the most out of the program, while also feeling at home within the school community.

There’s a reciprocity—they want the right students, and parents want the right school—that goes well beyond academic ability.

The admission process begins with the completion of an online application, and SJK begins accepting applications in August, more than a year in advance. Atypical for private schools, SJK does not have an application deadline, instead stipulating that the process is on a first-come, first-served basis. Once spaces are filled, no more applications will be accepted for the upcoming school year.

Successful applicants are notified by the school, and are then requested to set up a school visit and provide supporting documentation. Students enrolling in grades 6 through 10 are asked to write an entrance test. Also fairly atypical in the world of private school, students are then asked to attend a day of classes, during which they are paired with an enrolled student. This occurs during the school year prior to the one that the student is applying to enter.

There is no cost associated with application, though new Canadian Day students are asked to pay a non-refundable registration fee of $3,000 at the time of enrollment. Families of Boarding students and International Day students are asked to pay $5,000 upon enrollment. Only successful applicants pay this one-time fee.

In June, newly enrolled families are invited to attend events where they have opportunities to meet other families, teachers and administrators in advance of their child’s first day at school.

Money matters

Tuition for a JK Day student entering SJK for the 2023/24 school year is $22,490, including the one-time registration fee for a new student. Tuition for Day students increases as the student progresses, reaching a maximum of $33,900 for a returning Grade 12 student.

Tuition for returning Boarding students in grades 9 to 12 is $75,840. Tuition for returning International day students in grades JK to 8 is $47,655. Multi-child discounts are applied to the third and fourth child only.

Tuition covers instruction and all activities associated with the delivery of the core program. Not included are bus transportation, uniforms, school supplies, and fees associated with extracurricular activities. Families can opt into a hot food program at the beginning of the year, and parent Anne Spruin enthuses at the quality of the food and the choices available to students.

That can sound like a lot of incidentals, though parents reliably report that there are few, if any, surprises along the way, and that prices are fair.

Financial aid

“There is a cost to coming to the school,” says Britt Leeking, Director of Enrolment. “But we are continuing to work to make this school accessible to students who would benefit from it.”

A number of scholarship and bursary opportunities are available to students whose families demonstrate financial need. Assistance is only available to Canadian students.

“We’re not just looking for the kids who are the straight-A students and are doing well,” says Leeking, “we’re looking for students who can benefit from our program, and who can reach their potentials because of our environment.” Financial aid initiatives are designed to help bring those mission-appropriate students to the school.

Parents and alumni

The parents we spoke to, virtually without exception, spoke glowingly of the culture and the community that the school provides. Families report that communication with the school is regular, with weekly updates from teachers. Parents report that prompt email responses from teachers are typical.

The connections between parents, too, are significant, encouraged perhaps by the events that dot the school calendar. “I don’t think I’ve ever missed a carol service,” says alumni parent Anne Huntley of the holiday event.

The school has worked hard to rebuild community among families following the difficult pandemic period when engagement wasn’t possible. “The 50th anniversary events were an opportunity to come on campus and meet other parents,” says parent Anne Spruin.

Spruin has also participated actively in the school’s parents’ association and finds volunteering to be a good way to make connections. Events such as fundraisers provide diverse opportunities for parents and grandparents.

The takeaway

Perhaps understandably, many parents turn to private school for academic reasons, and that’s true of SJK as well. The IB programme is a draw, particularly because the school offers the full continuum, but also because it only offers the one stream: all students are in the same IB boat, as it were. That offers a good focus for the school, unequivocally set on the IB curriculum and the values that inform it. As you see in the display near the front foyer, this is a school dedicated to that one approach, and is appreciative of all that it offers the student population.

That said, parents with a longer experience of the school are more likely to talk about the community and the culture of the school, often in stridently glowing terms. “It’s about the quality of education, knowing where my kids are at all times. The continuity,” says Jennifer Shingler. “I feel envious that my children get to do their education in that environment.”

Yes, the athletics facilities are excellent, the curriculum challenging, but you’re equally likely to hear about the connections formed at the family skate on the pond. Parents appreciate all of that, and certainly the students do, too. SJK has a lot to offer, including simply belonging to a community that shares a set of core values and a perspective on the world. For many students, that alone is a transformative experience.