The York School KEY INSIGHTS

Each school is different. The York School's Feature Review excerpts disclose its unique character. Based on discussions with the school's alumni, parents, students, and administrators, they reveal the school’s distinctive culture, community, and identity.

What we know

- The York School is the definition of an urban school, one that identifies with, reflects, and makes significant instructional use of the urban context.

- Character programs and staff development illustrate a commitment to building positive relationships as the foundation for learning.

- Innovative programs give life and breadth to a strong core academic program.

- The York School was created to appeal to learners who are inclined toward academic achievement.

Our editor speaks about the school (video)

Handpicked excerpts

Every school is unique, and The York School is particularly adept at proving the point. Just in terms of the basics, it’s an IB, gender-inclusive day school in downtown Toronto, and that constellation of attributes alone makes it stand out. It’s also true that every school has its own culture and its own character, and The York School is a particularly good example of that as well. With the latest developments, the school has truly arrived, and the evidence for that is ample. The leadership brings a unique, fresh take to the entire project of learning. It’s supported by a significant program of care, exemplified by an active, engaged wellness team.

ON THE PHYISCAL ENVIRONMENT

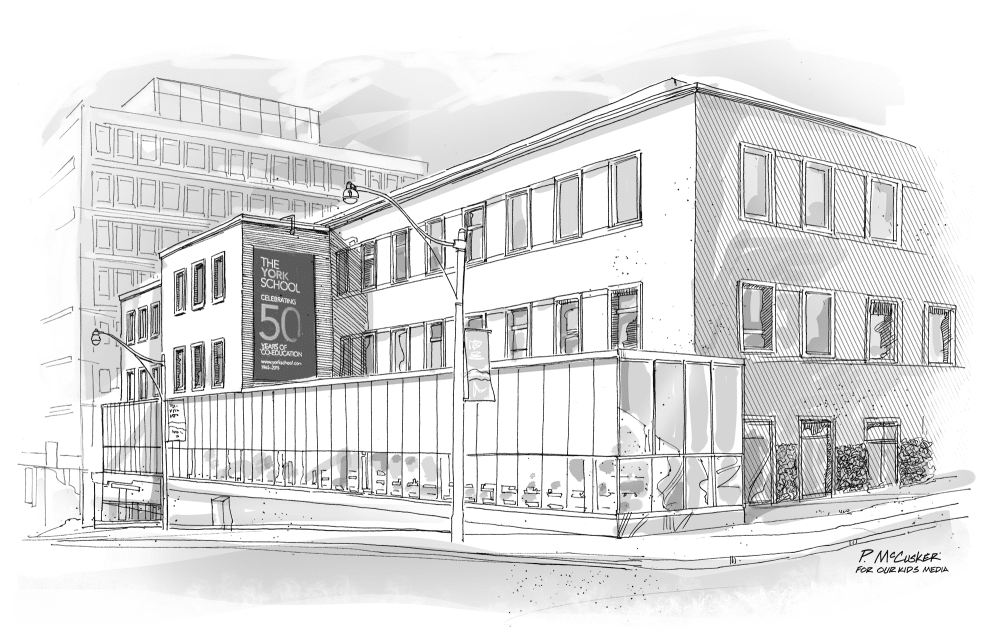

Founded in 1965, York grew to become the definition of an urban school, due largely to how it interacts with the learning opportunities the city provides. It’s one thing to be located within a city, and yet another to have a significant, daily interface with the surrounding city, something that York demonstrates better than most, both literally and figuratively. The entry to 1320 Yonge, home to both the Middle and Senior Schools, is akin to a modern subway entrance—students walk down a ramp and turn to enter the main doors rather than, say, walking up a flight of stairs and through an ivy-draped arch.… But the administration delights in those kinds of misconceptions. It means they’ve intentionally created a space that blurs the lines between the life and culture of the school, and the life and culture of the city beyond.

The students appreciate that blurred line between city and school. They see themselves as true urbanites, and they comport themselves in that way, with confidence and independence. The closest subway station is 200 metres from the school; the next closest isn’t much further. It’s an easy walk from either Summerhill or St. Clair station, past coffee shops, a Book City outlet, cafés, grocery stores, offices—all the bustle that Torontonians rightly delight in.

The Junior School reflects the feel of the main campus—there are lots of clean lines and a very modern design—though perhaps in a cozier way. There are open spaces, with lots of wood and warm lighting. While it is a part of The York School, it does have a lovely character of its own. The play spaces to the back can be seen from various points in the building, including the JS principal’s office.…. She looks out on the playground, and the children there are free to look in and see her working, meeting with teachers and parents. Says the principal, “What I love most about the space is that I can open the window and I can hear the children playing.” That underscores a porousness of the environment, one that the students find comforting—this is their space, and they have access to all of it.

ON THE ACADEMIC PROGRAM

Marks matter, says the director of university counselling, but each student’s story—how they develop over their time at the school—matters, too. “We provide those vehicles where students can grow into something pointy. The whole notion of a well-rounded student is not the ultimate goal ... well-rounded in everything, awesome in nothing. We want our students to have a story where they’re a little different in something, and that’s going to separate them from the pack.... And if we can align that pointiness with their post-secondary aspirations, fantastic. Consequently, that is giving our kids the edge, in addition to the marks, to getting [into] some of these more selective programs.”

ON THE ACADEMIC ENVIRONMENT

Struan Robertson says, “At the end of the day, I think what parents are looking for is a safe, happy place.... It’s when you walk in the building, how does the building make you feel? When you talk to kids, are they happy? ... That feeling that you can’t always describe, but when you walk in, you think, ‘this feels really good.’” That doesn’t just happen. The school needs to adopt it as a goal and then take steps to develop it, and The York School scores high on both counts.

ON THE WELLNESS PROGRAM

Elissa Kline-Beber, Associate Head, Wellbeing, told us “the relationships kids have with the adults in the building are powerful,” something staff and faculty work hard to foster. “One of the strengths of being a small school is that I can say with confidence that, if a student is really struggling, someone here is going to know about it.… When teachers have noticed that a child is struggling, I’ll get, in a day, four or five phone calls, saying, ‘Do you know what’s happening here?’”

ON UNIVERSITY COUNSELLING

“We shouldn’t be asking kids what they want to do when they grow up. We should be asking them what problems they want to solve when they grow up.”

—Director of university counselling

The process, says the director, begins with creating opportunities for students to try new things, make mistakes, experience success, grow, and persevere. “Then in Grades 9 and 10, we focus in a bit more on what you like to do, find the things that make you tick. Not the things that you want to be when you grow up, but find the things that you’re good at, that you like and want to improve in, and start to develop your story. And then in [Grades] 11 and 12, it’s about having the capacity to articulate that story.” If they want to be an engineer, he wants them to know exactly why, to be self-aware of their talents. Ultimately, he works with them to find a school: “I will help them find the best soil to plant their aspirations into.”

That attention is continued in a university counselling office that is as good or better than we’ve seen anywhere. If schools aren’t yet looking to York as an example of how best to counsel students in their move to post-secondary education, they should. In all, it’s not just about beginning early and being attentive, it’s also about perspective, and the one evidenced here is, frankly, inspiring.

ON THE STUDENT COMMUNITY

The York School was created to appeal to learners who are inclined to academic achievement, and who share a specific approach to learning. It would be wrong to say that all the students at the school today are similar—certainly that’s not true anywhere—but the ones we met shared some attributes, including a positive outlook and a willingness to dig in to some of the unique aspects of the offering.

The school population includes students from 35 different countries. That’s unique for a day school, and something York rightly sees as a strength. Talking about world issues in a classroom with so much international experience and perspective can bring conversations to life. A student commented that York is “a small school, but it’s big enough. It’s big enough that when people annoy you, you have some place to go. But it’s not so big that you don’t have to come back and deal with it later.” … We asked a classroom of students what they like about the school, and the first response was, “I like these people.”

There are 755 students in total. The national median for secondary schools is 350, so even though the York population is divided between two campuses, it still isn’t tiny. That said, what the students respond to aren’t the demographics or the enrolment numbers, but rather the lived experience of the school. They feel it’s small because it feels close knit. As one student noted, “we all know each other’s names.” That kind of thing doesn’t just happen, but rather is a function of how the school has managed its population over the years. Peer mentoring, as well as teachers that teach across grades, helps to reduce the sense of the size of the school. “There is a great student-teacher relationship and a continuum that doesn’t end when a student moves into the next grade,” says parent Scott Rattee. “Teachers are invested in the children until the day they graduate.” The students feel they all know each other, and because of their interactions throughout the school and the development of those ongoing teacher-student relationships, they do.

ON THE ATHLETIC PROGRAM

“Sport is a great educator,” says Rick DeMarinis, director of athletics, “and learning takes place on the field, on the court,” ranging from interpersonal skills to learning the value of activity. He feels competition is important for advancing in a sport. That’s certainly relevant for some students, particularly at the high school level, though DeMarinis is clear that competition isn’t for everyone, nor should it be. “For younger athletes, it’s about fostering an appreciation for sport and activity.”

“I think it’s about balance, and balance for me doesn’t mean you have to be involved in everything. For me, it means you have outlets in life that bring you happiness and pleasure, whatever that is. And I think that’s what we promote here.” All that said, DeMarinis is a champion of the idea that everyone needs a physical outlet—going for a walk, yoga, strength training, team sports—and he actively promotes offerings that range from recreational to competitive.

THE OUR KIDS REPORT: The York School

Next steps to continue your research: