155 years of Trinity College School

A notable birthday for a notable Canadian institution

“I had an accident with gunpowder,” wrote Peter Perry in his diary. He was a student in the very first cohort at TCS and maybe a bit of a handful. That was one of his first entries, in its entirety. In time his diary entries became more detailed, certainly longer, if equally enigmatic. “Thursday, [April] 12th," he wrote in another, "rainy all day. Dinner: veal and roly-poly. Did not take any pudding. Mr. Badgley's table did not take any because it was so bad."

From day one—founded in 1865, TCS is celebrating its 155th birthday this year—the life of the school was lively, and not at all the kind of environment that we might assume was common to Victorian-era boarding schools. As with Perry's diary, it’s easy to be charmed by the accounts that exist from that time. Instructors included the “handsome Mr. Litchfield,” and Mr. Sefton, “a very jolly Englishman who knew all about church music.” Sergeant-Major Goodwin was “a thorough old soldier who boasted on having attained his 18th birthday on the very day that he fought at Waterloo, was adored by all the boys. … when he was not teaching [he] always had a bunch of boys round him who listened with delight to his many stories of military life.” Goodwin established the school’s cadet corps, and drilled students in the use of cavalry swords “which were worn with a great deal of ceremony going to and from the drill ground.”

TCS began in 1865 in a rectory in Weston, Ontario, and was created to offer an Anglican education to boys in the area. It was called the Weston School, and was founded by Rev. William Arthur Johnson, a man who was, in every conceivable way, a product of his time. He was born in Bombay, India, where his father was posted as Quartermaster-General to the British forces stationed there. When his father retired that post in 1819, the family moved to a parsonage near Bromley in Kent, England. William was granted an education appropriate to his class within a very class-conscious age: he was groomed to take a place in the administration of the commonwealth, just as his father before him.

But, it wasn’t to be. Instead, William came to Canada seeking adventure, married Laura Jukes, and moved into a log cabin that he built for her with his own hands. He farmed a bit, took part in the rebellion, and otherwise sketched and painted watercolours. He also studied plants and insects, which was something of a fad at the time, though Johnson indulged his passion more than most: his collection of nearly 1600 microscope slides was later donated to the Academy of Medicine in Toronto, where it remains today.

At 30 he decided to join the clergy, and the service he offered his congregation led to a decision to start a school. In the first term, there were nine students and a faculty of four. His three sons were the first students on the register, and he took in the sons of friends as well. The register has been kept to this day, and all students are placed on it when they enter the school. Albert, Johnson’s eldest son, is #1. Sir William Osler is #27. Frank Darling, who would one day become the architect of the school buildings (as well as the architect of U of T’s Convocation Hall, Victoria College, and the Bank of Montreal building which now houses the Hockey Hall of Fame) is #17. Peter Jennings, the ABC news anchor, is #4150. Businessman and philanthropist Edgar Bronfman Sr. (#3786) attended at the same time as the philosopher Charles Taylor (#3985). Reginald Fessenden, inventor of the radio, is #847.

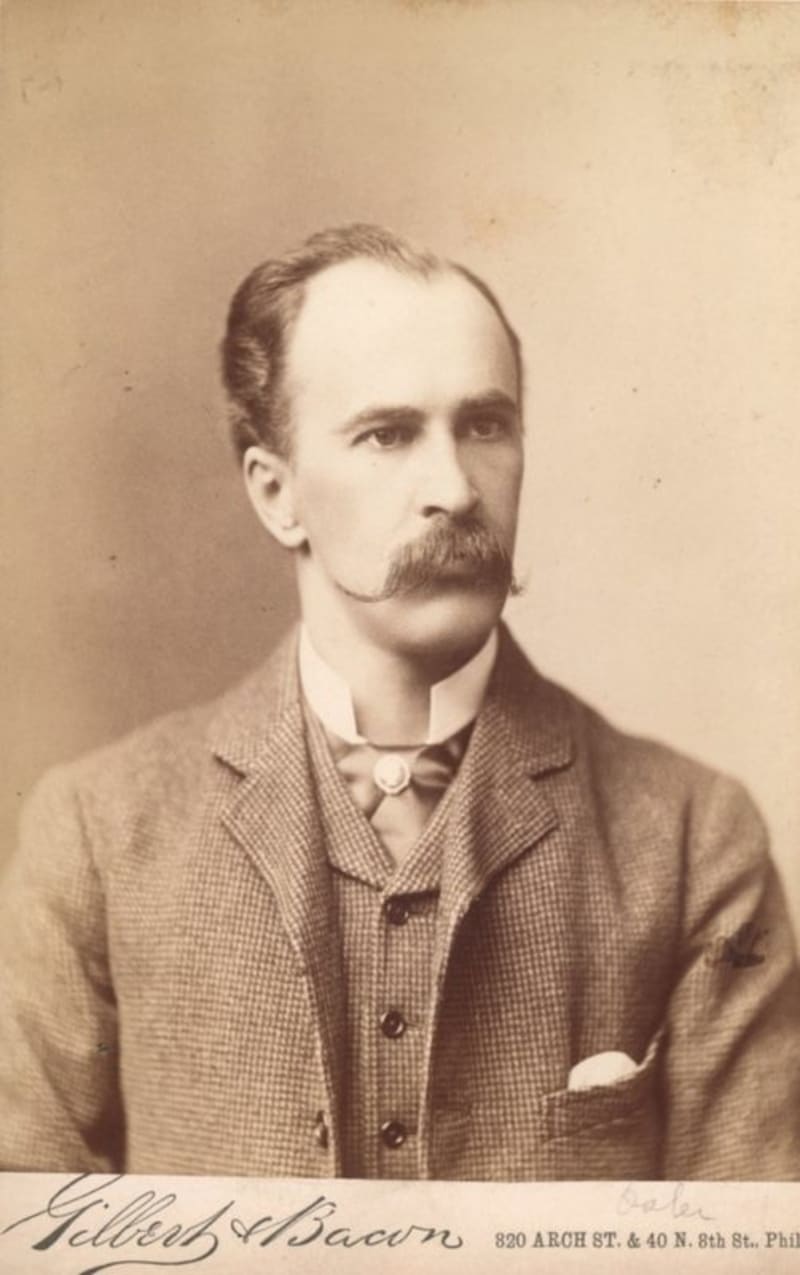

William Osler was the first head boy at Trinity College School, one of a long string of impressive achievements that he was to chart over his lifetime. He later became co-founder of Johns Hopkins hospital, and was knighted in 1911. The thing he is rightly best remembered for today is his impact on how medicine is taught and practiced. He believed the best approach to care was an empathetic one, and that it was best learned at the bedside. The result was the concept of the medical residency, which remains the cornerstone of medical education today. Osler’s seminal work is The Principles and Practice of Medicine, a book he dedicated to William Arthur Johnson, his teacher and the founder of TCS.

William Osler was the first head boy at Trinity College School, one of a long string of impressive achievements that he was to chart over his lifetime. He later became co-founder of Johns Hopkins hospital, and was knighted in 1911. The thing he is rightly best remembered for today is his impact on how medicine is taught and practiced. He believed the best approach to care was an empathetic one, and that it was best learned at the bedside. The result was the concept of the medical residency, which remains the cornerstone of medical education today. Osler’s seminal work is The Principles and Practice of Medicine, a book he dedicated to William Arthur Johnson, his teacher and the founder of TCS.

To underwrite growth, Johnson applied for a partnership with the corporation of Trinity College, now part of the University of Toronto, and with it the name was changed to Trinity College School. Johnson set the tone for the school, one that is felt to this day. He emphasized outdoor education, taking boys on field trips, sharing with them his enthusiasm for natural science along the way. His approach was that of growing knowledge through engagement. “[Johnson’s] concept of education did not lie in the greatest number of facts that could be drilled into his boys,” wrote A. H. Humble, an early historian of the school, “but in ideas and pursuits that would stimulate and excite the unfolding mind.”

The school came into prominence under the leadership of Charles Bethune, who reluctantly accepted the role of headmaster in 1870. Reluctance is perhaps too kind a word—he was fairly irascible, didn’t love the thought of a life in administration or even education, and the school was dangerously in debt. “When Dr. Bethune became headmaster,” wrote the editor of The Record in 1899, “there was only a wooden building on the present site, and the school work was conducted in rooms in the town.” The first task was to literally build the school and grow the enrolment. And he did. By the second year, Bethune had increased the student body by half, and by 1872 they were moving into the first building created specifically to house the school.

There was a renegade, frontier spirit in Bethune’s leadership, and one that he also brought to the school’s programs. At most private schools at the time, chapel sermons were no different than what you would hear in a typical church. At TCS, they “went far beyond the limits of time for ordinary sermons [yet] held the boys in rapt attention.” In one, the Archdeacon Vincent of Moosonee spoke about life in the north, and afterward “there were few, if any, who … did not think to be a missionary in Moosonee would be one of the happiest things possible.” (One student, R. J. Renison, actually became one.)

Bethune ultimately stayed on in the role for 29 years, something that even he seemed to marvel at. It was a period during which—as a result of his leadership—the school was incorporated and grew in size, stature, and reputation. Soon, students arrived from Iowa, Montreal, and even the west coast, despite the fact that the Canadian Pacific Railway had yet to be completed. Students loved him. He was seen as kind and fair, something he imparted to the character of the school he developed. One of the most moving and repeated moments in the school’s history is when Bethune arrived at the 50th-anniversary celebration in 1915 and was given a spontaneous, lasting ovation.

“My uncle is that gentleman up there,” says Steph Feddery pointing to one of the portraits that look down from the walls of the dining hall. “My family would come down and spend holidays here. I lived in the Lodge for about six months at one point, and my aunt was the archivist at the time, so I picked her brain a lot. It is fascinating when you look around and see the history and the names.”

The history provides a sense of tradition and place, one that the administration rightly seeks to maintain. “When we created the strategic plan,” says Stuart Grainger, “we asked ‘What is going to be the key to Trinity College School?’ And no matter what is going on in the world, we have to stand for integrity, compassion, kindness. And those values are referenced from 100 years ago. The history is in a series of personalities that sat in the same place that you are sitting in now. So that appreciation, respect, value-oriented leadership, value-oriented living, still remains as fundamental to living a purposeful life.”

Feddery has had a front-row seat for a considerable amount of its recent development, despite still being young. She enrolled in 1991, entering the school with the first cohort of girls—TCS was a boys’ school for the first 125 years of its life. “My brother had already been here for a year, and it was very overwhelming because there was a lot of animosity toward us. … a lot of the seniors were bothered when the girls arrived. Of course, some welcomed us with open arms,” she says, chuckling as she does.

“Things changed, and things were supposed to change anyway, but bringing in the girls exacerbated that. … But I had a great time, and made awesome friends that I’m still friends with today. It’s an experience. I was living away from home. I had focused on tasks that I had to accomplish here: routines, schedules. And because there was a small group of girls—there were 60 of us in the first year—we were all in the same boat, experiencing the same things.”

The inclusion of girls within the student body paved the way for more women on faculty, of which Feddery is an example. She’s also the master of Wright House. “Having female role models in the science and math classrooms has really helped,” she says. “When I was here there weren’t very many female teachers. There were a few, but I didn’t happen to have them.” Unlike when she began, the school now has a history of coed education, with photos and paintings of girls and women up there on the walls with the men, something that Feddery feels is important. She’s up there too, in a photo from her days on the volleyball team. “My students used to mock me incessantly. ‘Miss Feddery I see you on the wall!’ … But just for them to see that you’re an alum, I think it’s very powerful … I think for girls to see girls in science and girls in math is quite powerful.”

It is. Since the beginning, the focus has been both on a strong academic program as well as developing character, interpersonal skills, and a dedication to service. When headmaster Grainger says that, as educators, “you just want to have an impact on a kid’s life,” it’s clear that he truly means it. The dedication to diversity within the student population, including financial diversity, is evidence of that, and something that the school manages particularly well. He and other program leaders have an energy that they have brought to bear on the life of the school, including a dedication to addressing students’ lifestyles, and an attention to balance as much as achievement. They, as well as a very modern facility, keep the traditions and values in view.

—by Glen Herbert

For more, see the Our Kids Feature Review of Trinity College School.

Regina Christian schools

Find the top private and independent Christian schools in Regina (May 16, 2024)

Concord private schools

Find the top private and independent schools in Concord (May 16, 2024)

Kimberley private schools

Find the top private and independent schools in Kimberley (May 16, 2024)

Riverview private schools

Find the top private and independent schools in Riverview (May 16, 2024)

Balancing academics and social-emotional well-being

The art of providing holistic learning environments for teens (May 13, 2024)