Fred Genesee, a professor within the psychology department at McGill, has made a career of studying language acquisition and bilingualism. He writes that “historical documents indicate that individuals and whole communities around the world have been compelled to learn other languages for centuries and they have done so for a variety of reasons—language contact, colonization, trade, education through a colonial language, and intermarriage.”

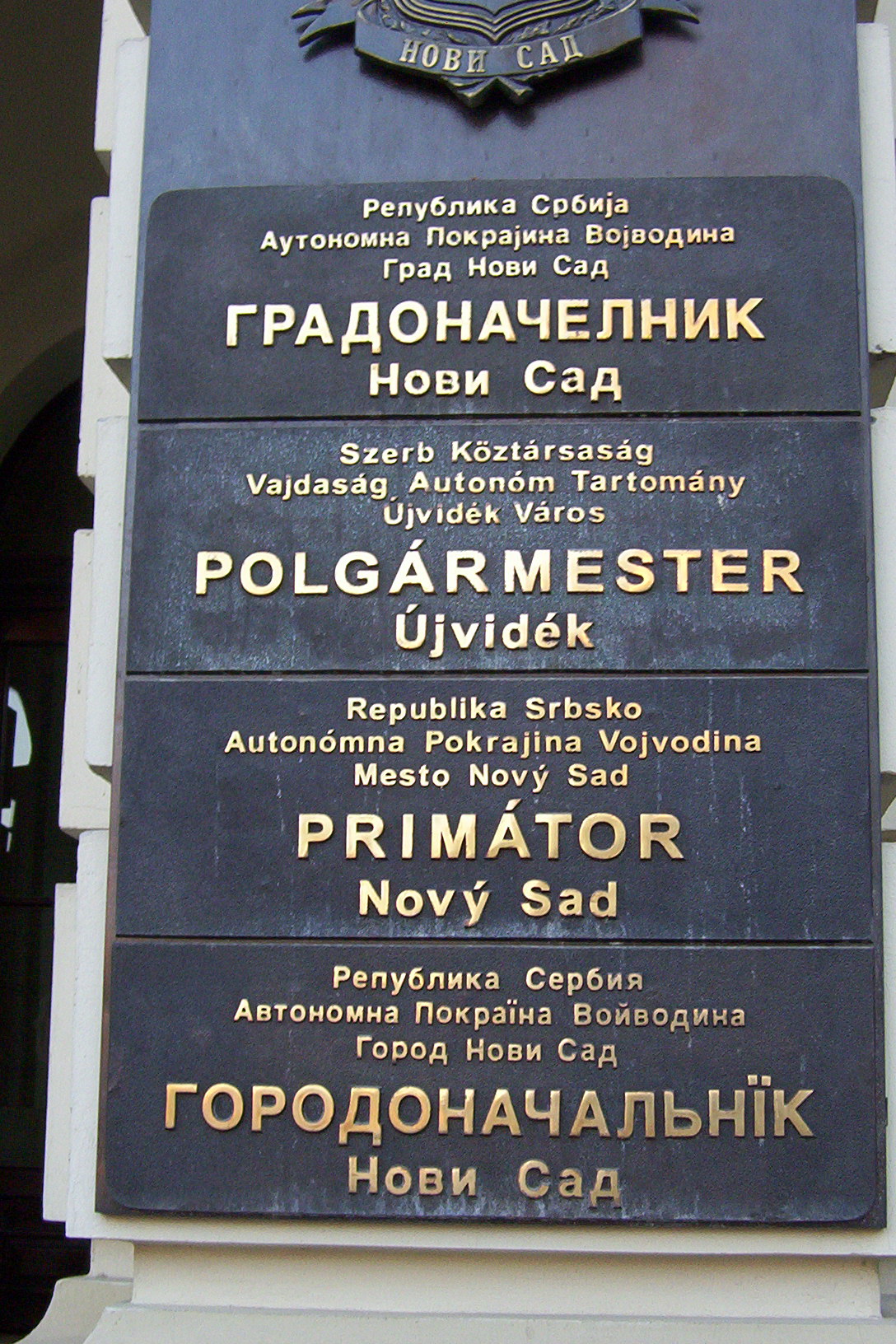

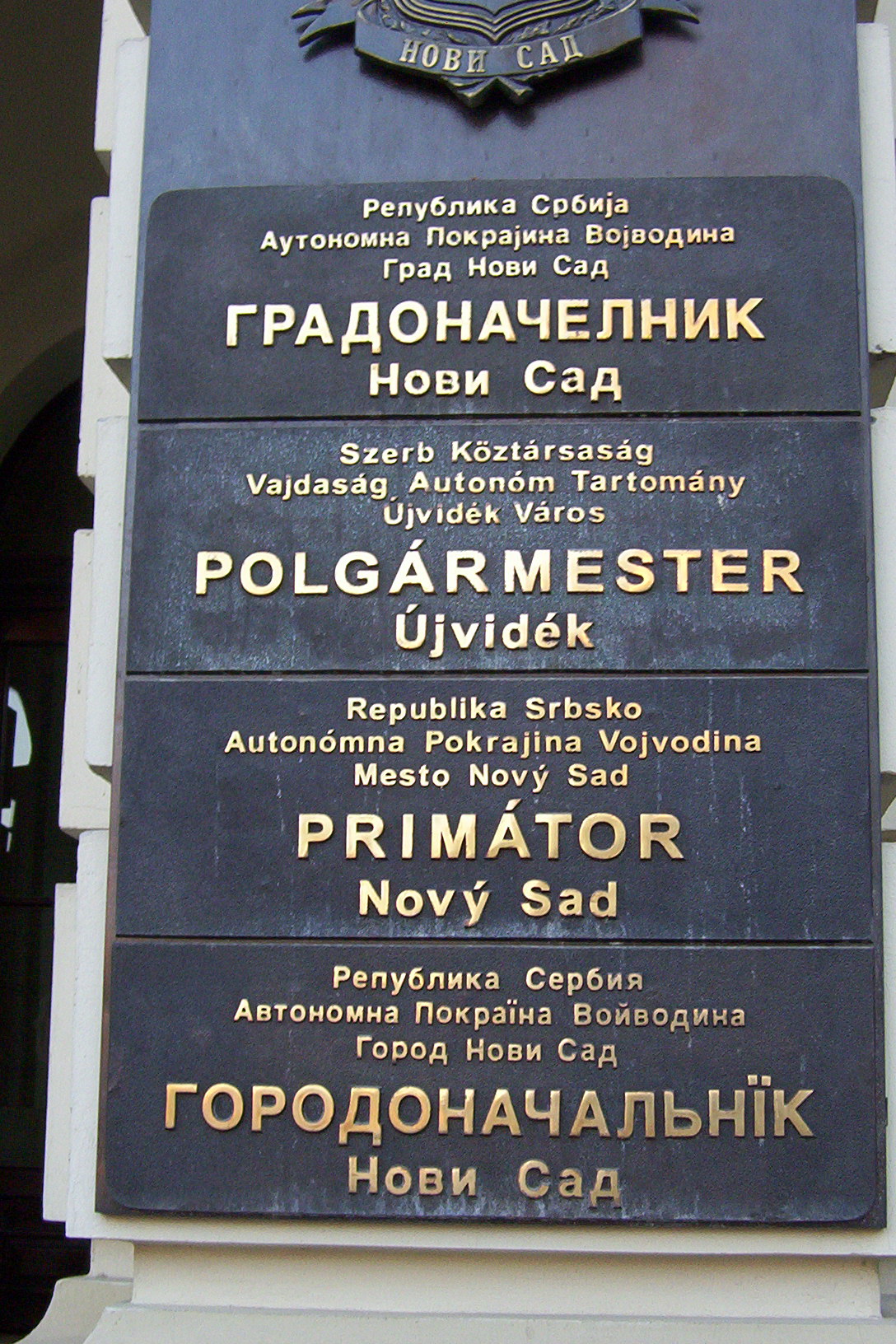

The Rosetta Stone offers a hint of that. Created more than 2000 years ago, it presents a decree outlining the intentions of the new ruler, Ptolemy, in the languages of the people over which ruled: ancient Egyptian, demotic, and Greek. It’s an example of something that many people live with today. The sign outside the mayor’s office of Novi Sad, Siberia (shown at right) is its own kind of Rosetta Stone, presenting the same information in the four official languages of the city: Serbian, Hungarian, Slovak and Pannonian Rusyn. Certainly, many countries reflect that level of linguistic diversity, if not more. Switzerland has four official languages. South Africa has 11, including Xhosa. It’s a tonal language, and it's a job just to say its name, as the “x” is a click. While English is one of South Africa’s official languages, considerably more people speak Xhosa as their mother tongue.

How many languages do we need?

Still, there is a common belief that bilingualism isn’t as important as it once was, and that the benefits of bilingualism are increasingly limited. English feels like a global language, and in any case, technology, many believe, can otherwise help smooth any communication gaps. Max Ventilla, the founder of AltSchool and a rising star in the world of 21st-century literacies, commented recently that “if the reason you are having your child learn a foreign language is so that they can communicate with someone in a different language twenty years from now—well, the relative value of that is changed, surely, by the fact that everyone is going to be walking around with live-translation apps.”[1]

However, there are indications that those kinds of assumptions may not be entirely true. Based on his research, Fred Genesee believes that the internet, increased international travel and migration, and the growth of global markets creates more incentives for students to learn languages, not less.

“The Internet makes global communication available and easy, whether it be for personal, professional, commercial, or other reasons. On the one hand, this has created a particular need for proficiency in English as a lingua franca on the internet. On the other hand, as with economic globalization, global communication via the internet has also created the possibility of much greater communication in regional languages. Indeed, domination of the internet by English is giving way to a much stronger presence of regional and local languages as e-commerce takes hold and begins to commit resources to communicating with local and regional markets. In fact, there are presently more internet sites in languages other than English.”[2]

Content-based language instruction

The term “immersion” is the one we typically use when we talk about intensive language instruction. As it suggests, students are immersed within a language, such as French, German, or Mandarin, and they learn the language through the need to use it on a day-to-day basis.

While that’s true—that’s exactly what language immersion is intended to provide—a more accurate term is content-based language instruction. Just as we think of immersion, says Genesee, “content-based language instruction holds that people do not learn language and then use it, rather, they learn language by using it.”[3]

"Content" in this instance doesn’t refer only to whatever thoughts and ideas a student may be expressing, but to curriculum content specifically. Students don’t learn French in isolation, rather they learn science with French as the language of instruction. That’s how the French immersion programs across Canada are structured. Students spend a portion of their day in a French setting, and a portion in an English setting, with the core curriculum divided between them. Science, for example, will be taught in French throughout a student’s high school career, with literature and art, say, taught in English.

The result, in language schools, is not simply providing a need for students to use a language, but also to use it constructively. In a content-based setting, writes Genessee, “cognitive and social development proceed naturally along with language development [and] language is a tool children use to understand the world around them and to become full-fledged members of their social-cultural communities.”

The benefits of a bilingual education

The main goal of a bilingual language school is, of course, proficiency in two languages. That said, the degree of proficiency isn’t necessarily what some might believe it to be, nor is it ever the only goal.

TFS is a pioneer of language immersion in Canada. The school was founded in 1964, pre-dating the national multicultural movement of the 60s and 70s. As such it had, and retains to this day, a distinct flavour. Students are immersed in the French language, and all graduate fluent in both English and French. Likewise, cultural literacy is very much foregrounded, most obviously in the use of the French National Curriculum, first devised at the time of the French Revolution. Citizenship, unsurprisingly, is a core element, with language seen as a primary element in participation within a cultural community. In keeping, a goal of the program is to provide students not only with a facility with language, but also an awareness of their active participation in the wider world.

Fluency

A criticism of language immersion schools is often that students, on graduating, may not speak the second language as naturally as a native speaker would. Certainly, it’s true that few, by and large, reach that level of comfort and agility within the second language. The reality is that in many schools no one actually believes they will. To gain that level of ability—a fluid, natural use of grammar, idiom, and creativity—isn’t possible outside of a consistent linguistic culture. The only way to speak like a Parisian is to live in Paris; the only way to achieve true fluency in Japanese is to live and communicate, every day, in Japanese within a Japanese cultural context.

That said, the goals that programs do set for their students are achieved regularly, including opportunities to:

- Gain bilingual competence: To furnish students win an ability to use a first and second language effectively and appropriately for authentic personal, educational, social, and/or work-related purposes.

- Develop expression: Develop the ability to think creatively and flexibly, and more properly express their thoughts to a variety of people and in a variety of settings.

- Enhance/support cognitive development: It has been found that people who can speak two or more languages are less easily distracted and have more mental capacity for storing information than their unilingual counterparts. Bilingualism also helps offset declines in mental performance that comes with age, and bilingual people tend to show a higher performance in examinations and tests.

- Increase employability: Bilingual workers experience higher rates of employment, can enter the job market more easily, and can switch jobs more easily than their unilingual counterparts. More generally, the global nature of today's business world requires employees who can communicate between cultures and overcome language barriers.

Cultural literacy

In a paper delivered to the fourth International Symposium on Bilingualism, Mary Maguire quoted from an interview she conducted with a Chinese immigrant parent identified as Mrs. Li: “Language is like a door which enables you to learn the world. When you learn one language you get to know one part of the world. When you learn other languages, you will get an opportunity to know other parts of the world.” [4]

Maguire is professor emerita in McGill’s Department of Integrated Studies in Education. She used that quote to underscore the relationship between language and cultural literacy. Learning a language can provide students with a more intensive, and ultimately more meaningful, engagement with other cultural traditions. Likewise, learning a heritage language—one that is spoken by parents or grandparents—can provide a more authentic connection to ancestry and increased access to literature from that culture.

That said, through her research Maguire has found that learning languages isn’t just about information or understanding, but can have an impact on identity and a sense of cultural space. Maguire writes that “places are both physical territories with clearly defined borders and culturally constructed spaces through intricate social networks of social relationships.” Language, she suggests, can contribute to a sense belonging and identity within a cultural space, something that she feels is confirmed within the experience of the multilingual population of Montreal.

What Maguire goes on to suggest, however, is that within immigrant communities, language can create new identities that derive from an understanding of place that isn’t limited to one cultural community, but extend to the community of people who share a multiple cultural heritage. The term of art is “third space,” coined by Edward Soja. While he wrote primarily about geographical spaces, Maguire applied the concept to language acquisition and a sense of belonging within unique cultural spaces: “a new space between cultural collectives and individuals and historical periods.” She writes that “the expression of the self and the construction of the identity are both enabled and constrained by the appropriation of the linguistic and rhetorical conventions.” For example, children living in Montreal, Quebec, who are conversant in English, French, and Armenian, will inhabit a larger and likely richer cultural space than, say, a resident of Montreal who is conversant in only one of those languages.

On a larger scale, there is a greater cultural diversity within many languages than there is in English. Parisian French is distinct from Quebecois, for example, in more fundamental ways that English spoken in New York is distinct from that spoken in London. Likewise, French dialects spoken in Polynesia or Africa are more distinct still. Learning French, then, can provide a window onto a range of cultural spaces, and a greater breadth of cultural and historical understanding. It's something that critics of language programs, as Max Ventilla, often fail to recognize: languages are expressions of culture and, for some, can afford a sense of belonging and identity. Likewise, learning languages can enhance an understanding of local, national, and global historic and cultural diversity.

Types of immersion

Developmental bilingual education refers to immersion programs intended for students who share a first language and are all gaining proficiency in the same second language. French immersion in Ontario, for example, is intended for English speakers learning French as a second language.

Two-way immersion is less common in Canada, while more common on other parts of the world. These programs admit students for whom either instructional language is their first language. For example, schools that offer French and English and that admit enrollment of both Anglophone and Francophone students.

The German International School Toronto (GIST) is an example of two-way immersion, or dual immersion, with some students for whom German is their first language, and others for whom English is their first language. Students need to use both languages not just to interact with the coursework, but also to make themselves understood to their peers.

It’s also an example of how the value of language learning can go well beyond communication. Many immersion schools, such as GIST and the Alexander von Humboldt German International School in Montreal, use the immersion experience to develop social competencies, including empathy, personal engagement, and cooperation.

Those schools, and those like them, have developed in very different ways, and for very different purposes than the French immersion model that Canadians are most familiar with. “These schools were originally intended to be for expats, parents on foreign assignment,” says Manfred von Volte, vice principal of GIST. The school has taught English since it began in 2000, though language instruction wasn’t the only organizing principle. Equally important, if not more so, was instruction that reflected the core program of study used in schools in Germany. It is the system that some students were coming from, and also the one that some, presumably, would enter should their parents repatriate prior to the end of their elementary or secondary school careers.

While the international German schools—there is a network of 140 of them dotted around the globe—soon attracted the attention of the local community, recognizing the rich and unique educational opportunity the schools offered. The school in Egypt, and others in South America, today have student populations in excess of 1000 students.

Says von Volte, “When you have this situation—where you have two languages, children from around the world, students that are the new students—they are all facing some hurdle of one sort or another.” They may be from different places, speak different languages, have different abilities or strengths, though they share the experience difference, and live each day with the challenges of making themselves understood across languages and cultures. Increasingly those social benefits attract families and students to language schools, in addition to the benefits of bilingualism.

Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR)

If there is a manifesto of immersion, the CEFR is undoubtedly it. Francis Goullier, one of the chief architects of the CEFR, describes it as an “action-oriented approach to modern languages” and that “the usefulness of the CEFR is that it reminds us that competences vary in nature and all contribute to pupil success. … it lays stress on the combination between task execution and one or more language activities; it emphasizes the importance of the authenticity of situations in relation to pupils’ communication needs.”

The framework was created by the Council of Europe and launched in 2001 in order to provide A) concrete guidelines around optimal language instruction, and B) an objective tool for employers to use when evaluating language qualifications. To that end, CEFR describes five key linguistic competencies:

- existential competence, an ability to communicate thoughts and ideas;

- linguistic competence, an ability to use grammar correctly;

- sociolinguistic competence, an ability to speak naturally and appropriately, using politeness conventions and idioms;

- pragmatic competence, an ability to organize, structure, and sequence thoughts and arguments;

- general knowledge, and the vocabulary with which to express it.

The framework also recognizes that true fluency requires an ability to adjust usage appropriately between four main settings—educational, occupational, public, and personal—and to be able to engage with others appropriately.

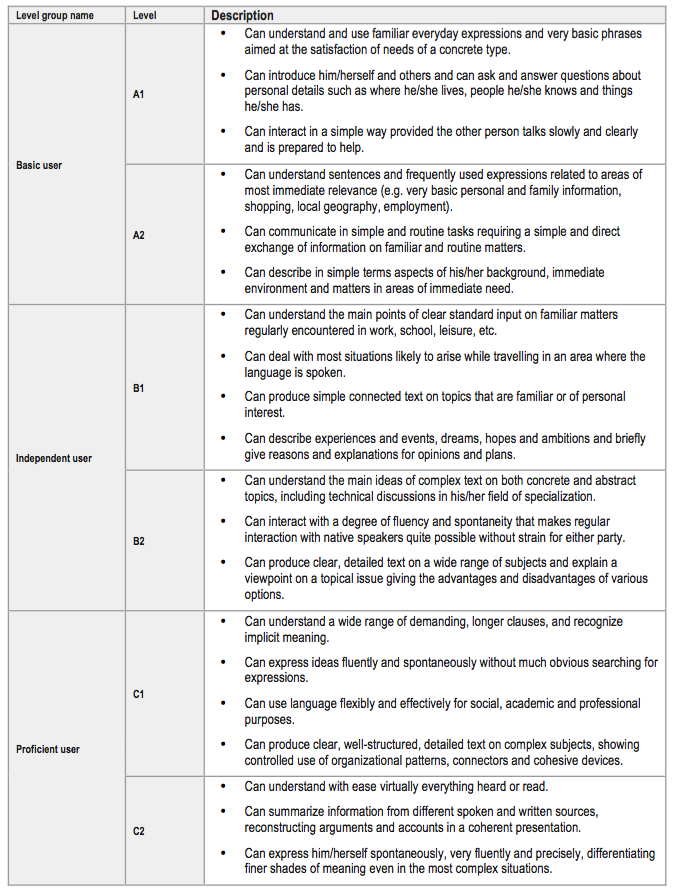

The most compelling piece of the framework, however, is how it expresses the goals of language instruction, in turn also providing an objective means of assessing linguistic competence. Grammar is important, of course, but the proof of the pudding is in the abilities that the learner gains. The levels of competence that CEFR outlines are keyed, famously, to “can do” statements, shown in the right-hand column in Table 1 below.

Table 1: CEFR Levelling

The SIOP instructional model

The Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP) was developed in the US for the purposes of English language instruction, specifically for students entering English-language schools and for whom English is a second language. It was developed as a framework for delivering language instruction through the presentation of the core academic curriculum. While the protocol wasn’t developed with language immersion programs specifically in mind (it was developed for non-English speakers entering English-only schools) some schools have adopted the model. For the most part, SIOP is a formalized presentation of the concepts that inform content-based language instruction akin, at least in intention, to the CEFR.

Is younger better?

There is an abundance of anecdotal evidence—if not clinical evidence—to support the idea that children learn second languages more quickly than adults or even older students. And, as a generalization, they do. Sharon Lapkin is professor emeritus at OISE in Toronto. She says, “It’s easier. It’s play based. They’re doing things that young children do and [language] is acquired quite easily, painlessly.”

Younger children are better able to replicate intonation, the sounds of language, and therefore are less likely to speak with an accent. The relation between age and accent is fairly predictable: age 13. “I have a friend that came here when she was about 12 and her brother was 13,” says Lapkin. “He has an accent and she doesn’t.” It’s sometimes referred to as the Kissinger Effect, given that Henry Kissinger has a very pronounced accent while his younger brother doesn’t. There, too, 13 appears to be the deciding age. Of course, reality doesn’t always conform, though at least in terms of the sounds within language, and the ability to replicate them, age can at times be a significant factor.

Still, language acquisition is complex, and not simply a function of age or brain development. Personality and disposition are factors as well. When his brother Walter was asked about the different accents, he quipped “unlike Henry, I listen to other people.” And, in fact, there may be a bit of truth in that. Lapkin notes that desire, and a drive to learn, can be equally important as exposure and opportunity. “The higher the staring grade, the more the student is opting in or out, rather than the parents. So, if it’s a grade seven student, for example, there’s probably going to be some self-selection into the program. … But there are all kinds of other things going on [as well]. The older student may have had an exchange opportunity, contact with real experiences in the other languages. There may have been an online contact, maybe an online pen pal or that kind of thing,” that can create a unique impetus to excel.

What remains true throughout is that there is a positive correlation between exposure to a second language and proficiency, and students of any age can gain proficiency. It’s also clear that the most successful programs provide continuous instruction in the second language; teach language through core curricula, not in isolation from it; include a social imperative to use the second language.

The ideal immersion program

When considering immersion, these are the things you should be looking for:

- extended opportunities to use the second language

- authentic opportunities to express genuine thoughts and ideas

- instruction that is based in an imperative to use the second language to interact with peers and to acquire knowledge

- use of communicative tasks that promote task-specific vocabulary and usage

- a setting that reflects the learner’s personal goals, be they linguistic, cultural, or social

The ideal immersion student

“There is no evidence that immersion is just for the smart kids,” says Lapkin. “The more educated parent is more aware of options, they go to parent meetings, and are more likely to opt in.” However, notes Lapkin, that’s changing. “Immersion is more firmly established, and parents are more aware of it as an option. There is a greater awareness that bilingual education has not been shown to confuse struggling learners, or to limit academic achievement.”

Likewise, the benefits of a bilingual education have been demonstrated for students with a wide range of learner characteristics, including those who may be at risk for poor academic performance. “We know that immigrants thrive in immersion programs,” says Lapkin. “There is even research to the effect that children with a learning disability will do as well as they would do” in a unilingual academic setting.

Part of the concern around academic performance arises from findings showing that immersion students score lower than their English-only peers during the primary grades. Specifically, they score lower on tests of reading and writing in English. “These lags disappear within one year of receiving English language arts instruction,” writes Genesee. “The rapid catch-up in reading and writing in English that early total [immersion] students experience is often attributed to the transfer of reading and writing skills in French to English and the fact that they have extensive exposure to English outside school.”

Series: Language Immersion Schools